It did not take him long to discover that the task of conveying Lady Ingham on a journey was no sinecure. She was exacting and she changed her mind almost hourly. No sooner had he gone off with her old coachman to inspect her travelling carriage (kept by her long-suffering son in his coach-house and occupying a great deal of space which he could ill spare) than she decided that it would be better to travel post. Off went Tom in a hack to arrange for the hire of a chaise, only to find on his return to Green Street that she had remembered that since Muker would occupy the forward seat they would be obliged to sit three behind her, which would be intolerable.

“I am afraid,” said Lord Ingham apologetically, “that you have taken a troublesome office upon yourself, my boy. My mother is rather capricious. You mustn’t allow her to wear you to death. I see you are lame, too.”

“Oh, that’s nothing, sir!” said Tom cheerfully. “I just take a hack, you know, and rub on very well!”

“If I can be of assistance,” said Lord Ingham, in a dubious tone, “you—er—you must not hesitate to apply to me.”

Tom thanked him, but assured him that all was in a way to be done. He could not feel that Lord Ingham’s assistance would expedite matters, since he knew by now that the Dowager invariably ran counter to his advice, and was exasperated by his rather hesitant manners. Lord Ingham looked relieved, but thought it only fair to warn Tom that there was a strong probability that the start would be delayed for several days, owing to the Dowager’s having decided at the last minute that she could not leave town without a gown that had not yet been sent home by her dressmaker, or some article that had been put away years before and could not now be found.

“Well, sir,” said Tom, grinning, “she had the whole set of’em turning the house out of the windows to find some cloak or other when I left, but I’ll bring her up to scratch: see if I don’t!”

Lord Ingham shook his head, and when he repaired to Green Street on the appointed day to bid his parent a dutiful farewell it was in the expectation of finding the plans changed again, and everything at odds. But Tom had made his word good. The old-fashioned coach stood waiting, piled high with baggage; and Lord Ingham entered the house to find the travellers fully equipped for the adventure, and delayed only by the Dowager’s sudden conviction that her curling-tongs had been forgotten, which entailed the removal of everything from her dressing-case, Muker having packed them at the bottom of it.

Lord Ingham, eyeing young Mr. Orde with respect, was moved to congratulate him. Young Mr. Orde then confided to him that it had been a near-run thing, her la’ship having been within ames-ace of crying off as late as yesterday, when the weather took a turn for the worse. “But I managed to persuade her, sir, and I think I shall be able to get her aboard Thursday’s packet all right and tight,” said optimistic Tom.

Lord Ingham, casting an apprehensive glance at the hurrying clouds, thought otherwise, but refrained from saying so.

20

Lord Ingham was right. The first glimpse caught of the sea afforded the Dowager a view of tossing grey waters, flecked with foam; and long before she was handed down from the coach at the Ship Inn she had informed Tom that a regiment of Guards would not suffice to drag her on board the packet until the wind had abated. Two days of road travel (for to avoid fatigue she had elected to spend one night at Canterbury) had given her the headache; and during the rest of the journey she became steadily more snappish. Her temper was not improved, on alighting at Dover, by having the hat nearly snatched from her head by a gust of wind; and it seemed for several minutes as though she might re-enter the coach then and there, and return to London. Fortunately Tom had written to bespeak accommodation for the party; and the discovery that the best bedchamber had been reserved for her, and the best parlour with fires kindled in both, mollified her. A dose of the paregoric prescribed by Sir Henry Halford, followed by an hour’s rest, and an excellent dinner did much to restore her, but when Tom told her that the packet had sailed for Calais that day as usual, from which circumstance it might be inferred that no danger of shipwreck attended the passage, she replied discouragingly: “Exactly what I am afraid of!”

On the following morning, in conditions described by knowledgeable persons as fair sailing weather, Tom made the discovery that fair sailing weather, in Lady Ingham’s opinion, was flat calm. April sunshine lit the scene, but Lady Ingham could see white crests on the sea, and that was enough for her, she thanked Tom. An attempt to convince her that a passage of perhaps only four hours with a little pitching would be preferable to being cooped up in a stuffy packet for twice as long succeeded only in making her pick up her vinaigrette. She begged Tom not to mention that horrid word pitching again. If he and Phoebe had set their hearts on the Paris scheme she would not deny them the treat, but they must wait for calm weather.

They waited for five days. Other travellers came and went; Lady Ingham and Party remained at the Ship; and Tom, forewarned that the length of the bills presented at this busy hostelry was proverbial, began to entertain visions of finding himself without a feather to fly with before he had got his ladies to Amiens.

Squally weather continued; the Dowager’s temper worsened; Muker triumphed; and Tom, making the best of it, sought diversion on the waterfront. Being a youth of an inquiring turn of mind and a friendly disposition he found much to interest him, and was soon able to point out to Phoebe the various craft lying in the basins, correctly identifying brigantines, hoys, sloops, and Revenue cutters for her edification.

The Dowager, convinced that every haunt of seafaring persons teemed with desperate characters lying in wait to rob the unwary, was strongly opposed to Tom’s prowling about the yard and basins, but was appeased by his depositing in her care the packet of bills she had entrusted to him. It would have been better, in her opinion, had he and Phoebe climbed the Western Heights (for that might have blown Phoebe’s crotchets away), but she was forced to admit that for a man with a lame leg this form of exercise was ineligible.

It seemed a little hard to Phoebe that she should be accused of having crotchets when she was taking such pains to appear cheerful. She only once begged to be allowed to go back to Austerby; and since this lapse was the outcome of her grandmother’s complaining that she had allowed Mrs. Newbury to over-persuade her, it was surely pardonable. “Pray, pray, ma’am don’t let us go to Paris on my account!” she had said imploringly. “I only said I would go because I thought you wished it! And I don’t think Tom cares for it either, in his heart. Let him take me home instead!”

But the Dowager had been pulled up short by this speech. She was not much given to considering anyone but herself, but she was fond of Phoebe. Her conscience gave her a twinge, and she said briskly: “Fiddle-de-dee, my love! Of course I wish to go, and so I shall as soon as the weather improves!”

It began to seem, on the fifth day, that they were doomed to remain indefinitely at Dover, for the wind, instead of abating, had stiffened, and was blowing strongly off-shore. Tom’s waterfront acquaintances assured him that he couldn’t hope for a better to carry him swiftly across the Channel, but Tom knew that it would be useless to repeat this to the Dowager, even if she had not been keeping her bed that day. She was bilious. Sea-air, said Muker, always made my lady bilious, as those who had waited on her for years could have told others had they seen fit to ask.

So Phoebe, having the parlour to herself, tried for the fourth time to compose a letter to Sylvester that should combine contrition with dignity, and convey her gratitude for past kindness without giving the least hint that she wished ever to see him again. This fourth effort went the way of its predecessors, and as she watched the spoiled sheets of paper blacken and burst into flame she sank into very low spirits. It was foolish to fall into a reminiscent mood when every memory that obtruded itself (and most of all the happy ones) was painful, but try as she would to look forward no sooner was she idle than back went her thoughts, and the most cheerful view of the future which presented itself to her was a rapid decline into the grave. And the author of all her misfortunes, whose marble heart and evil disposition she had detected at the outset, would do no more than raise his fatal eyebrows, and give his shoulders the slight, characteristic shrug she knew so well, neither glad nor sorry, but merely indifferent.

She was roused from the contemplation of this dismal picture by Tom’s voice, hailing her from the street. She hastily blew her nose, and went to the window, thrusting it open, and looking down at Tom, who was standing beneath it, most improperly hallooing to her.

“Oh, there you are!” he observed. “Be quick, and come out, Phoebe! Such doings in the harbour! I wouldn’t have you miss it for a hundred pounds!”

“Why, what?”

“Never mind what! Do make haste, and come down! I promise you it’s as funny as any farce I ever saw!”

“Well, I must put on my hat and pelisse,” she said, not wanting very much to go.

“Lord, you’d never keep a hat on in this wind! Tie a shawl over your head!” he said. “And don’t dawdle, or it will all be over before we get there!”

Reflecting that even being buffeted by a cold wind would be preferable to further reverie, she said that she would be down in a trice, shut the window again, and ran away to her bedchamber. The idea of tieing a shawl round her head did not commend itself to her, but the Dowager had bought a thick travelling cloak with a hood attached for her to wear on board the packet, so she fastened that round her throat instead, and was hastily turning over the contents of a drawer in search of gloves when she was made to jump almost out of her skin by hearing herself unexpectedly addressed.

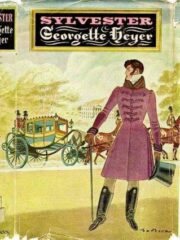

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.