“They are not her horses. They are mine.”

“You said yourself you kept them for her use: she must consider them as good as her own! Besides, you must know I couldn’t permit you to mount me!”

“I suppose you couldn’t,” he admitted. “I hate to see you so unworthily mounted, though.”

“Thank you—you are very good!” she stammered.

“I am what? Sparrow, I do implore you not to let Lady Ingham teach you to utter civil whiskers! You know I am no such thing, but, on the contrary, the villain whose evil designs drove you from home!” He stopped, as her eyes flew involuntarily to meet his. The look held for no more than an instant, but the expression in her eyes drove the laughter from his own. He waited for a moment, and then asked quietly: “What is it? What did I say to make you look at me like that?”

Scarlet-cheeked, she said: “Nothing! I don’t know how I looked.”

“Very much as I saw you look once at your mother-in-law: stricken!”

She managed to laugh. “How absurd! I am afraid you have too lively an imagination, Duke!”

“Well, I hope I may have,” he returned.

“There can be no doubt. I was—oh, shocked to think that after all that has passed you could suppose me to regard you in the light—in the light of a villain. But you were only funning, of course.”

“I was, but I’m not funning when I tell you that I was not maliciously funning—to distress you.”

She turned her head to look at him again, this time in candid appraisal. “No. Although it is a thing you could do, I fancy.”

“You may believe that I did not.”

“And you may believe I don’t think you villainous!”

“Oh, that is a much harder task!” he protested, rallying her. “When I think of the reception I was accorded at that appalling inn I have the gravest misgivings!”

She laughed, but tacitly refused the challenge. He did not pursue the subject; and after riding beside him in silence for a few minutes she introduced another, saying: “I had almost forgotten to tell you that I had the pleasure of meeting your nephew yesterday, Duke! You must be very proud of him: he is a most beautiful child!”

“He is a very spoilt one. Are you acquainted with my sister-in-law?”

“I made her acquaintance a few days ago, and she was so kind as to invite me to spend the afternoon with her yesterday.”

“Ah, now I understand the meaning of that stricken look!” he remarked. “Did I figure as the Unfeeling Brother-in-law, or as the Wicked Uncle?”

She was not obliged to answer him, for as the words left his tongue his attention was diverted. A lady who was walking beside the carriage-way just then waved to him. He recognized his cousin, Mrs. Newbury, and at once desired Phoebe to rein in. “If you are not already known to one another I should like to introduce you to Mrs. Newbury, Miss Marlow. She is quite the most entertaining of my cousins: I am persuaded you would deal extremely!—Georgie, what a stunning sight! How comes it about that you are walking in this demure style? No faithful husband to ride with you? Not one cicisbeo left to you?”

She laughed, stretching up her hand to clasp his. “No, isn’t it infamous? Lion has a spell of duty, and all my cicisbeos have failed me! Those who are not still buried in the country have their feet in mustard-baths, so that I’ve sunk to walking with a mere female. No, you can’t see her, because we have parted company.”

He had leaned down to take her hand, and now, just before he released it, he pressed it meaningly, saying: “Sunk indeed! Are you acquainted with Miss Marlow, or may I introduce her to you?”

“So that is who you are!” she said, smiling up at Phoebe. “To be sure, I should have guessed it, for I have just been exchanging bows with your cousins. You are Lady Ingham’s granddaughter, and—you are riding Anne Ingham’s deplorable slug! But you should not be: it is quite shocking! Even under that handicap you take the shine out of us all.”

“I have been trying to persuade her to let me have the privilege of mounting her, but she insists it will not do,” Sylvester said. “I have now a better notion, however. I fancy your second hack would be just the thing for her.”

Mrs. Newbury owned only one hack, but she had been on the alert from the moment of having her hand significantly squeezed, and she took this without a blink, interrupting Phoebe’s embarrassed protests to say warmly: “Oh, don’t say you won’t, Miss Marlow! You can’t think how much obliged to you I shall be if you will but ride with me sometimes! I detest walking, but to ride alone, with only one’s groom following primly behind, is intolerable! I am pining for a good gallop, too, and that can’t be had in Hyde Park. Sylvester, if I can prevail upon Miss Marlow to go, will you escort the pair of us to Richmond Park upon the first real spring day?”

“But with the greatest pleasure, my dear cousin!” he responded.

“Do say you would like it!” Mrs. Newbury begged Phoebe.

“I should like it of all things, ma’am, but it is quite dreadful that you should be obliged to invite me!”

“But I promise you I’m not! Sylvester knew I should be charmed to have a companion—and, you know, I could have said my other horse was lame, or sold, if I had wished to! I shall come to pay Lady Ingham a morning-visit, and coax her into giving her consent.”

She stepped back then, and as they parted from her cast a quizzing look up at Sylvester. He met it with a smile, so she concluded that he was pleased, and went on her way, wondering whether he was indulging a fit of gallantry, or if it was possible that he was really trying to fix his interest with Miss Marlow. It seemed unlikely, but no more unlikely than his having singled her out for his latest flirt. Or was he merely being kind to Lady Ingham’s countrified little granddaughter? Oh, no! not Sylvester! decided Mrs. Newbury. He could be kind, but only where he liked. Well, it was all very intriguing, and for her part she was perfectly ready to lend him whatever aid he wanted. One did not look gift-horses in the mouth, certainly not a gift-horse of Sylvester’s providing.

16

The encounter in the Park decided the matter: Sylvester was not to be immediately rebuffed. He had certainly made it almost impossible for Phoebe to do so, but this was a consideration that only occurred to her after she had made her decision. Without standing in the smallest danger of losing her heart to him, she found his company agreeable, and would be sorry to lose it. If he was trying to serve her as he had served the unknown Miss Wharfe there could be no better way of discomfiting him than by receiving his advances in a spirit of cool friendliness. This was an excellent reason for tolerating Sylvester; within a very short time Phoebe had found another. With the return to London of so many members of the ton quite a number of invitations arrived in Green Street; and Phoebe, attending parties in some trepidation, rapidly discovered the advantages attached to her friendship with him. Very different was her second season from the first! Then she had possessed no acquaintance in town; she had endured agonies of shyness; and she had attracted no attention. Now, though the list of her acquaintances was not large, she attracted a great deal of attention, for she was Salford’s latest flirt. People who had previously condemned Phoebe as a dowd with neither beauty nor style to recommend her now discovered that her countenance was expressive, her blunt utterances diverting, and her simplicity refreshing. Unusual: that was the epithet affixed to Miss Marlow. It emanated from Lady Ingham, but no one remembered that: a quiet girl with no pretension to beauty must be unusual to have captured Sylvester’s fancy. There were many, of course, who could not imagine what he saw in her; she would never rival the accredited Toasts, or enjoy more than a moderate success. Happily she was satisfied merely to feel at home in society, to have made a few agreeable friends, and never to lack a partner at a ball. No lady whose hand was claimed twice in one evening by Sylvester need fear that fate. Nor did Sylvester stand in danger of being rebuffed while he continued to treat her with just the right degree of flattering attention. His motive might be perfidious, but it could not be denied that he was a delightful companion; and one, moreover, with whom it was not necessary to mind one’s tongue. His sense of humour, too, was lively: often, if a fatuous remark were uttered, or someone behaved in a fashion so typical as to be ludicrous, Phoebe would look instinctively towards him, knowing that he must be sharing her amusement. It was strange how the dullest party could be enjoyed because there was one person present whose eyes could be met for the fraction of a second, in wordless appreciation of a joke unshared by others: almost as strange as the insipidity of parties at which that person was not present. Oh, no! Miss Marlow, though fully alive to his arrogance, his selfishness, and his detestable vanity had no intention—no immediate intention—of repulsing Sylvester.

Besides, he had provided for her use a little spirting mare with a silken mouth, perfect in all her paces, and as full of playfulness as she could hold. Phoebe had cried out involuntarily when first she had seen the Firefly: how could Mrs. Newbury bear to let another ride her beautiful mare? Mrs. Newbury did not know how it was, but she preferred her dear old Jupiter. Phoebe understood at once: she herself owned a cover-hack long past his prime but still, and always, her favourite hack.

It was not long before she had discovered the truth about the Firefly. Major Newbury, very smart in his scarlet regimentals, had seen his wife and her new friend off on their almost daily ride one day. He had come out on to the step leading up to the door of his narrow little house, and no sooner had he set eyes on the Firefly than he had exclaimed: “Is that the mare Sylvester gave you, Georgie? Well, by Jove—!”

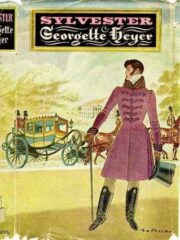

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.