But if she expected to receive a welcome from Horwich she was the more deceived. Persons who demanded admittance at unseasonable hours were never welcome to him, even when they arrived in a chaise-and-four and escorted by a liveried servant. A street lamp illumined the chaise, and he perceived that for all the dirt that clung to the wheels and panels it was an extremely elegant vehicle: none of your job-chaises, but a carriage built for a gentleman of means and taste. A glimpse of a crest, half concealed by mud, caused him to unbend a trifle, but he replied coldly to Keighley’s inquiry that her ladyship was not at home to visitors.

He was obliged to admit Phoebe, of course. He did it with obvious reluctance, and stood, rigid with disapproval, while she thanked Keighley for his services, and bade him goodbye with what he considered most unbecoming friendliness.

“I will ascertain whether her ladyship will receive you, miss,” he said, shutting the door at last upon Keighley. “I should inform you, however, that her ladyship retired to rest above an hour ago.”

She tried not to feel daunted, and said as confidently as she could that she was sure her grandmother would receive her. “And will you, if you please, look after my maid, Horwich?” she said. “We have been travelling for a great many hours, and I expect she will be glad of some supper.”

“I will that, and no mistake!” corroborated Alice, grinning cordially at Horwich. “Don’t you go putting yourself out, though! A bit of cold meat and a mug of porter will do me fine.”

Phoebe could not feel, observing the expression on Horwich’s face, that Sylvester had acted wisely in sending Alice to town with her. Horwich said in arctic accents that he would desire the housekeeper—if she had not gone to bed—to attend to the Young Person presently. He added that if Miss would be pleased to step into the morning-room he would send her ladyship’s maid up to apprise my lady of Miss’s unexpected arrival.

But by this time Phoebe’s temper had begun to mount, and she surprised the venerable tyrant by saying tartly that she would do no such thing. “You need not put yourself to the trouble of escorting me, for I know my way very well! If her ladyship is asleep I shall not wake her, and if she is not I don’t need Muker to announce me!” she declared.

Her ladyship was not asleep. Phoebe’s soft knock on her door was answered by a command to come in; and she entered to find her grandmother sitting up in her curtained bed, with a number of pillows to support her, and an open book in her hands. Two branches of candles and the flames of a large fire lit the scene, and cast into strong relief her ladyship’s aquiline profile. “Well, what is it?” she said testily, and looked round. “Phoebe! Good God, what in the world—? My dear, dear child, come in!”

A weight slid from Phoebe’s shoulders; her face puckered, and with a thankful cry of: “Oh, Grandmama!” she ran forward.

The Dowager embraced her warmly, but she was not unnaturally alarmed by so sudden an arrival. “Yes, yes, of course I am glad to see you, my love! But tell me at once what has happened! Don’t try to break it to me gently! Not, I do trust, a fatal accident to your papa?”

“No—oh, no! nothing of that nature, ma’am!” Phoebe assured her. “Grandmama, you told me once that I might depend on you if—if ever I needed help!”

“That Woman!” uttered the Dowager, sitting bolt upright.

“Yes, and—and Papa too,” said Phoebe sadly. “That was what made it so desperate! Something happened—at least, I believed it was going to happen—and I couldn’t bear it, and so—and so I ran away!”

“Merciful heavens!” exclaimed Lady Ingham. “My poor child, what have they been doing to you? Tell me the whole!”

“Mama told me that Papa had arranged a—a very advantageous marriage for me with the Duke of Salford,” began Phoebe haltingly. She was conscious that her grandmother had stiffened, and paused nervously. But the Dowager merely adjured her to continue, so she drew a breath, and said earnestly: “I couldn’t marry him, ma’am! You see, I had only met him once in my life, and I disliked him excessively. Besides, I knew very well that he didn’t so much as remember me! Even if I had liked him I couldn’t have borne to marry a man who only offered for me because his mother wished him to!”

The Dowager, controlling herself with a strong effort, said: “Is that what That Woman told you?”

“Yes, and also that it was because I had been brought up as I should be, which made him think I should be suitable.”

“Good God!” said the Dowager bitterly.

“You—you do understand, don’t you, ma’am?”

“Oh, yes! I understand only too well!” was the somewhat grim response.

“I was persuaded you would! And the dreadful thing was that Papa was bringing him to Austerby to propose to me. At least, so Mama said, for Papa had told her so.”

“When I see Marlow—Did he bring Salford to Austerby?”

“Yes, he did, but how he came to make such a mistake—unless, of course, Salford did mean to offer for me, but changed his mind as soon as he saw me again, which, I must say, no one could wonder at. I don’t know precisely how it may have been, but Papa was sure he meant to make me an offer, and when I told him what my sentiments were, and begged him to tell the Duke—he would not,” said Phoebe, her voice petering out unhappily. “So I knew then that there wasn’t anybody, except you, Grandmama, who could help me. And I ran away.”

“Alone?” demanded the Dowager, horrified. “Never tell me you’ve come all that distance on the common stage and by yourself!”

“No, indeed I haven’t!” Phoebe hastened to reassure her. “I came in Salford’s chaise, and he made me bring a—a maid with me, besides sending his groom to look after everything for me!”

“What?” said the Dowager incredulously. “Came in Salford’s chaise?”

“I—I must explain it to you, ma’am,” said Phoebe, looking guilty.

“You must indeed!” said the Dowager, staring at her in the liveliest astonishment.

“Yes. Only it—it is rather a long story!”

“In that case, my love, be good enough to pull the bell!” said the Dowager. “You will like a glass of hot milk after your journey. And I think,” she added, in fainter accents,” that I will take some myself, to sustain me.”

She then (to Phoebe’s alarm) sank back against her disordered pillows, and closed her eyes. However, upon the entrance of Miss Muker presently, she opened them again, and said with surprising vigour: “You may take that sour look off your face, Muker, and fetch up two glasses of hot milk directly! My granddaughter, who has come to pay me a visit, has endured a most fatiguing journey. And when you have done that, you will see that a warming-pan is slipped between the sheets of her bed, and a fire lit, and everything made ready for her. In the best spare bedchamber!”

When my lady spoke in that voice it was unwise to argue with her. Muker, who had responded to Phoebe’s greeting in a repressive voice, and with the slightest of curtsies, received her orders without comment, but said with horrid restraint: “And would Miss wish to have the Female which I understand to be her maid attend her here, my lady?”

“No, pray send her to bed!” said Phoebe quickly. “She—she is not precisely my maid!”

“So, if I may say so, miss, I apprehend!” said Muker glacially.

“Disagreeable creature!” said the Dowager, as the door closed behind her devoted abigail. “Who is this Female, if she is not your maid?”

“Well, she’s the landlady’s daughter,” Phoebe answered. “Salford would have me bring her!”

“Landlady’s daughter? No, don’t explain it to me yet, child! Muker will come back with the hot milk directly, and something seems to tell me that if we suffer an interruption I shall become perfectly bewildered. Take that ugly pelisse off, my love—good gracious, where did you have that dreadful gown made? Has That Woman no taste? Well, never mind! Whatever happens I’ll set that to rights! Draw that chair to the fire, and then we can be comfortable. And perhaps if you were to give me my smelling-salts—yes, on that table, child!—it would be a good thing!”

But although the story presently unfolded to her might have been thought by some to have been expressly designed to cast into palpitations any elderly lady in failing health, the Dowager had no recourse to her vinaigrette. The tale was so ravelled as to make it necessary for her to interpolate a number of questions, and there was nothing in her incisive delivery of these to suggest frailty either of body or intellect. The most searching of her inquiries were drawn from her by the intrusion into the recital of Mr. Thomas Orde. She appeared to be much interested in him; and while Phoebe readily told her all about her oldest friend she kept her eyes fixed piercingly upon her face. But when she learned of Tom’s nobility in offering a clandestine marriage to her granddaughter (“which threw me into whoops, because he isn’t nearly old enough to be married, besides being just like my brother!”) she lost interest in him, merely requesting Phoebe, in a much milder tone, to continue her story. There was nothing to be feared, decided her ladyship, from young Mr. Orde.

The last of her questions was posed almost casually. “And did Salford chance to mention me?” she asked.

“Oh, yes!” replied Phoebe blithely. “He told me that he was particularly acquainted with you, because you were his godmother. So I ventured to ask him if he thought you might—might like to let me reside with you, and he seemed to think you would, Grandmama!”

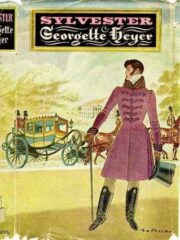

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.