“No! I never said that, or thought it!” she stammered. “How could I, when I scarcely knew you?”

“Oh, this is worse than anything!” he declared. “No sooner seen than disliked! I understand you perfectly: I have frequently met such persons—only I had not thought myself to have been one of them!”

Goaded, she retorted: “One does not, I believe!” Then she immediately looked stricken, and faltered: “Oh, dear, my wretched tongue! I beg your pardon!”

The retort had made his eyes flash, but the look of dismay which so swiftly succeeded it disarmed him. “If ever I met such a chastening pair as you and Orde! What next will you find to say to me, I wonder? Unnecessary, I’m persuaded, to tell you not to spare me!”

“Now that is the most shocking injustice!” she exclaimed. “When Tom positively toad-eats you!”

“Toad-eats me? You can know nothing of toad-eaters if that is what you think!” He directed a suddenly penetrating look at her, and asked abruptly: “Do you suppose that that is what I like? to be toad-eaten?”

She thought for a moment, and then said: “No, not precisely. It is, rather, what you expect, perhaps, without liking or disliking.”

“You are mistaken! I neither expect it nor like it!” She bowed her head, it might have been in acquiescence, but the ghost of a smile on her lips nettled him.

“Upon my word, ma’am—!” he said angrily, and there stopped, as she looked an inquiry. A reluctant laugh was dragged out of him. “I recall now that I was told that you were not just in the common way, Miss Marlow!”

“Oh, no! Did someone indeed say that of me?” she demanded, turning quite pink with pleasure. “Who was it? Oh, do pray, tell me!”

He shook his head, amused by her eagerness. It was such a mild compliment, yet here she was, all agog to learn its source, looking like a child tantalized by a toy held out of her reach. “Not I!”

She sighed. “How infamous of you! Were you hoaxing me?”

“Not at all! Why should I?”

“I don’t know, but it seems as though you might do so. People don’t say pretty things of me—or, if they do, I never heard of it.” She pondered it. “Of course, it might mean that I was merely odd—in a gothic way,” she said doubtfully.

“Yes—or outrageous!”

“No,” she decided. “It couldn’t have meant that, because I wasn’t outrageous when I went to London. I behaved with perfect propriety—and insipidity.”

“You may have behaved with propriety, but insipidity I cannot allow!”

“Well, you thought so at the time!” she said tartly. “And, to own the truth, I was insipid. Mama was watching me, you see.”

He remembered how silent and stupid she had appeared at Austerby, and said: “Yes, you must certainly escape from her. But not on the common stage, and not unescorted! Is that agreed?”

“Thank you,” she replied meekly. “I own it will be more comfortable to travel post. When shall I be able to set forward, do you think?”

“I can’t tell that. No London vehicles have gone by yet, which leads me to suppose that the drifts must be lying pretty thick beyond Speenhamland. Wait until we have seen the Bristol Mail go past!”

“I have a lowering presentiment that we shall see Mama’s travelling-carriage instead—and it will not go past,” stated Phoebe, in a hollow tone.

“I pledge you my word you shan’t be dragged back to Austerby—and that you may depend on!”

“What a very rash promise to make!” she observed.

“Yes, isn’t it? I am fully conscious of it, I assure you, but having given my word I am now hopelessly committed, and can only pray to heaven I may not find myself involved in any serious crime. You think I’m funning, don’t you? I’m not, and will immediately prove my good faith by engaging Alice’s services.

“Why, what can she do?” demanded Phoebe. “Go with you as your maid, of course. Come, come, ma’am! After such a strict upbringing as you have endured is it for me to tell you that a young female of your quality may not travel without her abigail?”

“Oh, what fustian!” she exclaimed. “As though I cared for that!”

“Very likely you do not, but Lady Ingham will, I promise you. Moreover, if the road should be worse than we expect you might be obliged to spend a night at some posting-house, you know.”

This was unanswerable, but she said mutinously: “Well, if Alice doesn’t choose to go I shan’t regard such nonsensical stuff!”

“Oh, now you are glaringly abroad! Alice will do precisely what I tell her to do,” he replied, smiling.

The easy confidence with which he uttered these words made her hope very much that he would meet with a rebuff from Alice, but nothing so salutary happened. Learning that she was to accompany Miss to the Metropolis, Alice fell into blissful ecstasy, gazing upon Sylvester with incredulous wonder, and breathing reverently: “Lunnon!” When it was disclosed to her that she should be given five pounds to spend, and her ticket on the stage for her return-journey, she became incapable of speech for several minutes, being afeared, as she presently informed her awed parent, to bust her stay-laces.

The thaw set in, and with it arrived the errant ostler, full of hair-raising accounts of the state of the road. Mrs. Scaling told him darkly that he would be sorry presently that he had not made a push to return immediately to the Blue Boar; and when he learned what noble guests she was entertaining he was indeed sorry. But when he discovered that the stables had fallen under the governance of an autocrat who showed no disposition to abdicate in his favour, but, on the contrary, every disposition to set him to work harder than he had ever done, he was not so sorry. He might have missed handsome largesse, but he had also missed several days of being addressed as “my lad”, and having his failings crisply pointed out to him, and being commanded to perform all over again such tasks as Keighley considered him to have scamped. Nor were his affronted sensibilities soothed by the treatment he received at Swale’s hands. Swale was forced to eat his dinner in the kitchen among the vulgar, but no power known to man could force him to notice the existence of a common ostler. So aloof was his demeanour, so disdainful his glance, that the ostler at first mistook him for his master. He discovered later that the Duke was more approachable.

The first vehicles to pass the inn came from the west, a circumstance which made Phoebe very uneasy; but a day later the Bristol Mail went by, at so unusual an hour that Mrs. Scaling said they might depend upon it the road was still mortal bad to the eastward. “Likely as not they’ve been two days or more getting here,” she said. “They do be saying in the tap that there’s been nothing like it since four years ago, when the river froze over in London-town, and they had bonfires on it, and a great fair, and I don’t know what-all. I shouldn’t wonder at it, miss, if you was to be here for another se’enight,” she added hopefully.

“Nonsense!” said Sylvester, when this was reported to him. “What they say in the tap need not cast you into despair. Tomorrow I’ll drive to Speenhamland, and discover what the mailcoachmen are saying.”

“If it doesn’t freeze again tonight,” amended Phoebe, a worried frown between her brows. “It was shockingly slippery this morning, and you will have enough to do in holding those greys of yours without having that added to it! I could not reconcile it with my conscience to let you set forth in such circumstances!”

“Never,” declared Sylvester, much moved, “did I think to hear you express so much solicitude on my behalf, ma’am!”

“Well, I can’t but see what a fix we should be in if anything should happen to you,” she replied candidly.

The appreciative gleam in his eyes acknowledged a hit, but he said gravely: “The charm of your society, my Sparrow, lies in not knowing what you will say next—though one rapidly learns to expect the worst!”

It did not freeze again that night; and the first news that greeted Phoebe, when she peeped into Tom’s room on her way downstairs to breakfast, was that he had heard a number of vehicles pass the inn, several of which he was sure came from the east. This was presently confirmed by Mrs. Scaling, who said, however, that there was no telling whether they had come from London, or from no farther afield than Newbury. She was of the opinion that it would be unwise to venture on such a hazardous journey until the snow had entirely gone from the road; and was regaling Phoebe with a horrid story of three outside passengers on the stage-coach who had died of the cold in just such weather, when Sylvester arrived on the scene, and put an end to this daunting history by observing that since Miss Phoebe was not proposing to travel to London on the roof of a stage-coach there was no need for anyone to feel apprehensive on her account. Mrs. Scaling reluctantly conceded this point, but warned his grace that there was a dangerous gravel-pit between Newbury and Reading, very hard to see when there had been heavy falls of snow.

“Like the coffee pot,” said Sylvester acidly. “I don’t see that at all—and I should wish to do so immediately, if you please!”

This had the effect of sending Mrs. Scaling scuttling off to the kitchen. “Do you suppose there really is any danger of driving into a gravel-pit, sir?” asked Phoebe.

“No.”

“I must say, it sounds very unlikely to me. But Mrs. Scaling seems to think—”

“Mrs. Scaling merely thinks that the longer she can keep us here the better it will be for her,” he interrupted.

“Well, you need not snap my nose off!” countered Phoebe. “Merely because you have come down hours before you are used to do!”

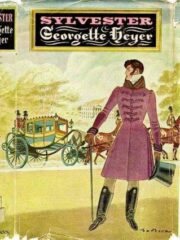

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.