“You do favour the blunt style, don’t you? Bluntly, then, ma’am, I was not.”

She was not at all offended, but said, with a sigh of relief: “Thank goodness! Not but what it is still excessively awkward. However, you are better than nobody, I suppose!”

“Thank you!”

“Well, when I heard you come in I hoped you had been that odious ostler.”

“What odious ostler?”

“The one who is employed here. Mrs. Scaling—she’s the landlady—sent him off to Newbury to purchase provisions when she feared they might be snowed up here for weeks, perhaps, and he has not come back. His home is there, and Mrs. Scaling thinks he will make the snow an excuse for remaining there until it stops. And the thing is that he has taken the only horse she keeps! Tom—Mr. Orde—won’t hear of my trying if I can ride Trusty—and I own it would be a little difficult, when there’s no saddle, and I am not wearing my riding-dress. And no one ever has ridden Trusty. True would carry me, but that’s impossible: his left hock is badly strained. But that leg is certainly broken, and it must be set!”

“Whose leg?” interrupted Sylvester. “Not the horse’s?”

“Oh, no! It’s not as bad as that!” she assured him. “Mr. Orde’s leg.”

“Are you sure it’s broken?” he asked incredulously. “How the deuce did he get here, if that’s the case? Who got the horses out of their traces?”

“There was a farm-hand, leading a donkey and cart. It was that which caused the accident: Trusty holds donkeys in the greatest aversion, and the wretched creature brayed at him, just as Tom had him in hand, as I thought. Tom caught his heel in the rug, I think, and that’s how it happened. The farmhand helped me to free Trusty and True; and then he lifted Tom into his cart, and brought him here, while I led the horses. Mrs. Scaling and I contrived to cut off Tom’s boot, but I am afraid we hurt him a good deal, because he fainted away in the middle of it. And here we have been ever since, with poor Tom’s leg not set, and no means of fetching a surgeon, all because of that abominable ostler!”

“Good God!” said Sylvester, struggling with a strong desire to laugh. “Wait a minute!”

With these words, he went out into the road again, to where Keighley awaited him. “Stable ’em, John!” he ordered. “We are putting up here for the night. There is only one ostler, and he has gone off to Newbury, so if you see no one in the yard, do as seems best to you!”

“Putting up here, your grace?” demanded Keighley, thunderstruck.

“I should think so: it will be too dark to go farther in another couple of hours,” replied Sylvester, vanishing into the house again.

He found that Phoebe had been joined by a stout woman with iron-grey curls falling from under a mob cap, and a comely countenance just now wearing a harassed expression. She dropped a curtsey to him; and Phoebe said, with careful emphasis: “This is Mrs. Scaling, sir, who has been so very helpful to my brother and to me!”

“How kind of her!” said Sylvester, bestowing upon the landlady the smile which won for him so much willing service. “Their parents would be glad to know that my imprudent young friends fell into such good hands. I have told my groom to stable the horses, but I daresay you will tell him just where he may do so. Can you accommodate the pair of us?”

“Well, I’m sure, sir, I should be very happy—only this is quite a simple house, such as your honour—And I’ve took and put the poor young gentleman in my best room!” said Mrs. Scaling, considerably flustered.

“Oh, that makes no odds!” said Sylvester, stripping off his gloves. “I think, ma’am, it would be as well if you took me up to see your brother.”

Phoebe hesitated, and when Mrs. Scaling bustled off to the back premises, said suspiciously: “Why do you wish to see Tom? Why do you wish to remain here?”

“Oh, it’s not a question of wishing!” he returned, a laugh in his eyes. “Pure fellow-feeling, ma’am! What a dog I should be to leave the poor devil in the hands of two females! Take me up! I promise you, he will be very glad to see me!”

“Well, I don’t think he will,” said Phoebe, regarding him in a darkling way. “And I should like to know why you talked of us to Mrs. Scaling as though you had been our grandfather!”

“I feel like your grandfather,” he replied. “Take me up to the sufferer, and let us see what can be done for him!”

She still seemed to be doubtful, but after a moment’s indecision she said ungraciously: “Oh, very well! But I won’t have him ranted at, or reproached, mind!”

“Good God, who am I to give him a trimming?” Sylvester said, following her up the narrow stair.

Mrs. Scaling’s best bedchamber was a low-pitched room in the front of the house. A fire had been lit in the grate, and the blinds drawn across the dormer window to shut out the bleak dusk. An oil lamp had been set on the dressing-table, and a couple of candles on the mantelshelf, and as the window-blinds and the curtains round the bed were of crimson the room presented a pleasantly cosy appearance. Tom, fully dressed except for his boots and stockings, was lying on the bed, with a patchwork quilt spread lightly over his legs, and his shoulders propped up by several bulky pillows. There was a haggard look on his face, and the eyes which he turned towards the door were heavy with strain.

“Tom, this—this is the Duke of Salford!” said Phoebe. “He would have me bring him up, so—so here he is!”

This startling intelligence made Tom wrench himself up on to his elbow, wincing, but full of determination to protect Phoebe from any attempt to drag her back to Austerby. “Salford?” he ejaculated. “You mean to tell me—Come over here, Phoebe, and don’t you be afraid! He has no authority over you, and so he knows!”

“Now, don’t you enact me a high tragedy!” said Sylvester, walking up to the bed. “I haven’t any authority over either of you, and I’m not the villain of this or any other piece. How do you do?”

Finding that a hand was being held out to him Tom, much disconcerted, took it, and stammered: “Oh, how—how do you do, sir? I mean—”

“Better than you, I fear,” said Sylvester. “In the devil of a hobble, aren’t you? May I look?” Without waiting for an answer he twitched the quilt back. As Tom instinctively braced himself, he glanced up with a smile, and said: “I won’t touch it. Have you been much mauled?”

Tom grinned back at him rather wanly. “Oh, by Jove, haven’t I just!”

“Well, I am very sorry, but we had to get your boot off, and we did try not to hurt you,” said Phoebe.

“Yes, I know. It wasn’t so much that as that booberkin thinking he knew how to set a bone, and Mrs. Scaling believing him!”

“It sounds appalling,” remarked Sylvester, his eyes on the injured leg, which was considerably inflamed, and bore the marks of inexpert handling.

“It was,” asseverated Tom. “He is Mrs. Scaling’s son, touched in his upper works, I think!”

“Well, he is a natural,” amended Phoebe. “Indeed, I wish I hadn’t allowed him to try what he could do, but he was not at all unhandy with poor True, which made me think he would very likely know how to set your leg, for such persons, you know, frequently have that kind of knowledge.” She saw that Sylvester was regarding her with mockery, and added defensively: “It is so! There is a natural in our village who is better than any horse-doctor!”

“You should have been a horse, Orde,” said Sylvester. “How many hours is it since this happened?”

“I don’t know, sir. A great many, I daresay: it seems like an age,” replied poor Tom.

“I am not a doctor—even a horse-doctor—but I fancy the bone should be set as soon as possible. We shall have to see what we can do. Oh, don’t look so aghast! I’m not going to make the attempt! We need Keighley—my groom. I shouldn’t be at all surprised if he knows how to do the trick.”

“Your groom?” said Phoebe sceptically. “How should he know anything of the sort, pray?”

“Perhaps he doesn’t, in which case he will tell us so. He put my shoulder back once, when I was a boy and dislocated it, and I recall that when the surgeon came he said he could not have done it better himself. I’ll call him,” said Sylvester, walking to the door.

He went out, and Tom turned wondering eyes towards Phoebe. “What the deuce brought him here?” he asked. “I thought he had been chasing us, but if that was the way of it what makes him care a button for my leg?”

“I can’t think!” said Phoebe. “But he didn’t come in search of me, that I do know! In fact, he says he didn’t come to Austerby to offer for me at all. I was never more relieved in my life!”

Tom looked at her in a puzzled way, but since he was a good deal exhausted by all he had undergone, and his leg was paining him very much, he felt unequal to further discussion, and relapsed into silence.

In a short space of time Sylvester came back, bringing Keighley with him, and carrying a glass half full of a rich brown liquid, which he set down on a small table beside the bed. “Well, Keighley says that if it is a simple fracture he can set it for you,” he remarked cheerfully. “Let us hope it is, therefore! But I can’t help feeling that the first thing to do is to get you out of your clothes, and into your nightshirt. You must be excessively uncomfortable!”

“Oh, I do wish you will persuade him to be undressed,” exclaimed Phoebe, regarding Sylvester for the first time with approval. “It is precisely what Mrs. Scaling and I wanted to do for him at the outset, but nothing would prevail upon him to agree to it!”

“You amaze me!” said Sylvester. “If I find him similarly obstinate Keighley and I will strip him forcibly. Meanwhile, Miss Marlow, you may go downstairs—if you will be so obliging!—and assist Mrs. Scaling to tear up a sheet for bandages. No, I know you don’t wish to leave him to our mercy, but, believe me, you are shockingly in the way here! Go and brew him a posset, or some broth, or whatever you think suitable to this occasion!”

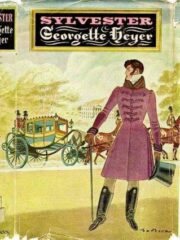

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.