That gave Sylvester the opportunity to ask her if she were related to a family of the same name living in Norfolk. She replied: “Shouldn’t think so, sir. Never heard of them until your grace mentioned them.”

As the family had no existence outside his imagination this was not surprising; but his question seemed to have broken the ice: Miss Battery, appearing slightly mollified, disclosed that she came from Hertfordshire.

Lady Marlow, breaking rudely in on this, said loudly that she had no doubt the Duke would enjoy a little music, and waved Phoebe towards the pianoforte.

Phoebe was an indifferent performer, but as neither her father nor Lady Marlow was at all musical they were perfectly satisfied, as long as she did not falter, or play any unmistakably wrong notes. Sylvester was not musical either, but he had been used to listen to the first musicians of the day, and thought he had never heard anyone play with less taste or feeling. He could only be thankful that she did not play the harp; but when, in response to some affectionate urging from her father, she sang an old ballad in a small, wooden voice he was much inclined to think that even a harp might have been preferable.

At half-past eight the schoolroom party withdrew, and after half an hour’s desultory conversation the tea-tray was brought in. Sylvester saw the end of his purgatory, and so it was. Punctually at half-past nine Lady Marlow informed him that they kept early hours at Austerby, bade him a formal goodnight, and went away, with Phoebe following in her wake. As they mounted the stairs she said complacently that the evening had gone off very well. She added that although she feared the Duke was a man of fashion, she was on the whole pleased with him. “Your father informs me that hunting will be out of the question tomorrow,” she observed. “If it should not be snowing I shall suggest to Salford that he might like to walk with you and your sisters. Miss Battery will accompany you, of course, but I shall tell her she may fall behind, with the girls, and give her a hint at the same time not to be putting herself forward, as I was excessively surprised to see her doing this evening.”

This programme, which, a few hours earlier, would have appalled her, Phoebe listened to with a calm born of her fixed resolve to be gone from Austerby long before it could be put into execution. Parting from Lady Marlow at the head of the stairs she went away to her bedchamber, knowing that both Susan and Miss Battery would come to her there, and that it would consequently be dangerous to repair to the morning-room before she had received these visitors.

Susan was soon got rid of; but Miss Battery, who followed her, showed a disposition to linger. Seating herself at the foot of the bed, and tucking her hands into the sleeves of her thick woollen dressing-gown, she told Phoebe that she thought she had done Sylvester less than justice.

“Sibby! You did not like him?” cried Phoebe.

“Don’t know him well enough to like him. I didn’t dislike him, at all events. No reason why I should: very civil to me!”

“Yes, to vex Mama!” Phoebe said shrewdly. “He was wanting to give her a set-down all through dinner!”

“Well,” said Miss Battery, “can’t blame him for that! Shouldn’t say so, of course, but there it is! Got a charming smile too.”

“I haven’t observed it.”

“You wouldn’t have taken him in such aversion if you had.I observed it. What’s more,” added Miss Battery candidly, “he bore your playing very well, you know. Most truly the gentleman! He must be bent on making you an offer to have solicited you for another song.”

She remained for several more minutes, but finding Phoebe deaf to whatever she chose to advance in Sylvester’s favour she presently went away; and Phoebe, after a discreet interval, slipped out of her room, and along the corridor to the west wing of the house. Here, besides the schoolroom, the nurseries, and various bedchambers, the morning-room was situated, a shabby apartment which, while still dignified by its original title, had dwindled into a mere sewing-room. It was lit by an oil lamp set in the middle of a bare table; and by this indifferent light young Mr. Orde, his overcoat buttoned up to his throat, sat reading a book of Household Hints, which was all the literature the room afforded. He seemed to have found it rewarding, for upon Phoebe’s entrance he looked up, and said with a grin: “I say, Phoebe, this is a famous good book! It tells you how to preserve tripe to go to the East Indies—which is just the sort of thing one might want to know any day of the week. All you need do is to Get a fine Belly of Tripe, quite fresh—”

“Ugh!” shuddered Phoebe, carefully shutting the door. “How horrid! Do put the book away!”

“All in good time! If you don’t want to know how to preserve tripe, what about an Excellent Dish for six or seven Persons for the Expense of Sixpence? Just the thing for the ducal kitchens, I think! It’s made with calf’s lights, and bread, and fat, and some sheeps’ guts, and—”

“How can you be so absurd? Stop reading that nonsense!” scolded Phoebe.

“Nicely cleaned!” pursued Tom. “And if you don’t fancy sheeps’ guts you may take hogs’, or—”

But at this point Phoebe seized the book, and after a slight struggle for possession he let her have it.

“For heaven’s sake don’t laugh so loud!” she begged him. “The children’s bedchamber is almost opposite this room! Oh, Tom, you can’t conceive what a shocking evening I’ve spent! I begged Papa to send the Duke away, but he wouldn’t, so I have made up my mind to go away myself.”

He was conscious of a sinking feeling at the pit of his stomach, but replied staunchly: “Well, I told you I was game. I only hope we don’t find the roads snow-bound in the north. Gretna Green it shall be!”

“Not so loud! Of course I’m not going to Gretna Green!” she said in an indignant under-voice. “Keep your voice low, Tom! If Eliza were to wake and hear us talking she would tell Mama, as sure as check! Now listen! I thought it all out at dinner! I must go to London, to my grandmother. She told me once that I might depend on her to do all she could for me, and I think—oh, I am sure she would support me in this, if only she knew what was happening! The only thing is—Tom, you know Mama buys all my dresses, and lets me have very little pin-money! Could you—would you lend me the money for the coach-fare? I think it costs about five-and-thirty shillings for the ticket. And then there is the tip to the guard, and—”

“Yes, of course I’ll lend you as much rhino as you want!” Tom interrupted. “But you can’t mean to travel to London on the stage!”

“Yes, I do. How could I go post, even if I could afford to do so? There would be the hiring of the chaise, and then all the business of the changes—oh, no, it would be impossible! I haven’t an abigail to go with me, remember! I shall be much safer in the common stage. And if I could contrive to get a seat in one of the fast day coaches—”

“Well, you couldn’t. They are always booked up as full as they can hold in Bath, and if you aren’t on the way-bill—Besides, if the snow is as deep beyond Reading as they say it is those coaches won’t run.”

“Well, never mind! Any coach will serve, and I don’t doubt I shall be able to get a place, because people won’t care to travel in this weather, unless they are obliged. I have made up my mind to it that I must be gone from here before anyone can prevent me, very early in the morning. If I could reach Devizes—it is nearer than Calne, and I know some of the London coaches do take that road—only I shall have a portmanteau to carry, and perhaps a bandbox as well, so—Oh, Tom, could you, do you think, take me to Devizes in your gig?”

“Will you stop fretting and fuming?” he said severely. “I’ll take you anywhere you wish, but this scheme of yours—You know, I don’t wish to throw a rub in the way, but I’m afraid it may not hold. This curst weather! A pretty piece of business it would be if you were to get no farther than Reading! It might well turn out so, and then it would be all holiday with you.”

“No, no, I have thought of that already! If the coach goes on, I shall stay with it, but if the snow is very bad I know just what I must do. Do you remember Jane, that used to be the maid who waited on the nursery? Well, she married a corn-chandler, in a very good way of business, I believe, and lives at Reading. So, you see, if I can’t travel beyond Reading I may go to her, and stay with her until the snow has melted!”

“Stay in a corn-chandler’s house?” he repeated, in accents of incredulity.

“Good God, why should I not? He is a very respectable man, and as for Jane, she will take excellent care of me, I can assure you! I suppose you had rather I stayed in a public inn?”

“No, that I wouldn’t! But—” He paused, not liking the scheme, yet unable to think of a better.

She began to coax him, representing to him the advantages of her plan, and all the hopelessness of her situation if she were forced to remain at Austerby. He was easily convinced of this, for it did indeed seem to him that without her father’s support her case was desperate. Nor could he deny that her grandmother was the very person to shield her; but it took a little time to persuade him that neither danger nor impropriety would attend her journey to London in a stage-coach. It was not until she told him that if he would not lend her his aid she meant to trudge to Devizes alone that he at last capitulated. Nothing remained, after that, but to arrange the details of her escape, and this was soon accomplished. Tom promised to have his gig waiting in the lane outside one of the farm gates of Austerby at seven o’clock on the following morning; Phoebe pledged herself not to keep him waiting there; and they parted, one of them full of confidence, the other trying to smother his uneasiness.

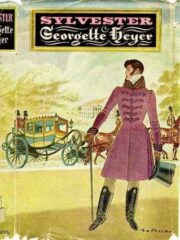

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.