As Gretchen, the military-looking one, stomps away, I can imagine which of the words were hers. Her disgust was apparent.

Which is fine with me. I’m not a fan of her personal style, either.

She’s obviously one of those girls who look down on those who have more opportunity in their lives. That giant chip on her shoulder is only going to keep her in her disadvantaged place.

Grace looks up at the house, her face a mixture of helplessness and determination. She seems nice enough, despite her insanity, and more the type to envy someone who has advantages than to despise them for it. The type to work hard to gain opportunities of her own. Why she’s let herself get sucked into this crazy delusion is beyond me, but at least there’s hope for her.

Finally, after what feels like forever, Grace leaves too, heading around the side of the house. I resist the urge to sprint to the living room, to spy out the side window and see if she is actually leaving.

Greer Morgenthal does not spy.

Frozen to my spot, staring out the window—at the drapes, actually, since I’ve let them fall back into place—my mind plays over everything they said. I would like to reject the idea that they are my sisters. I’m not adopted, as far as I know, but it also seems unlikely that Mother and Dad would have adopted out my two sisters if we were actually triplets. Not that Mother has ever been the most maternal sort. Quite the opposite. Still, I’ve always had the feeling that Dad wanted more children. I’ve spent my life trying to be enough for both of them. To be mature and classy and successful enough for Mother. To be loving and childlike and daughterly enough for Dad. If they were around more, I might have a schizophrenic break from the opposing efforts.

In any case, the idea that they would have given away my siblings doesn’t make sense.

Assuming I believe that Grace and Gretchen are my sisters—and I would have to be delusional myself to deny that physically obvious fact—that leaves me with only one logical conclusion: I am adopted.

I am surprisingly unaffected by the realization. Maybe Mother has trained all the emotion out of me. Maybe I truly am the ice queen my social enemies and ex-boyfriends so often claim. Perhaps I should cry or scream or feel betrayed in some essential way. A normal person would. Instead, I feel . . . relieved.

A surprising emotion. At least it is an emotion. I suppose, if I had ever analyzed my relationship with my parents in the past, the possibility might have occurred to me. I have never felt the elemental connection many of my friends have with their parents. Even when my friends claim to despise their parents, I sense the underlying indelible links. I’ve always felt like more of an accessory than an expression of love. I finally understand why.

The ever-present pressure lifts off my chest, and I feel like I can truly breathe for the first time since I took third place in the fifth-grade spelling bee and Mother punished me by sending me to my room without dinner. I’d disappointed her, and I have spent every day since trying to keep that from happening again. All this time, all this pressure, and the feeling of distance. It all makes sense. And it isn’t my fault.

I don’t know why the realization that I’m adopted clarifies everything in my mind, but it does. It’s like a frosted window has been removed from my vision.

Perhaps I should feel that my world has been rocked. And perhaps I should feel a little more off-kilter, considering the second startling claim my sisters made.

“A descendant of Medusa,” I muse, then immediately chide myself for even entertaining the thought.

What an absolutely ridiculous notion. As if such creatures of myth actually exist. They are nothing but stories, fables made up to help ancient man understand the inexplicable. To keep children obedient, lest they be fed to a dragon.

“Monster hunters.” I snort. “How ludicrous.”

But that resurrected memory floats into focus.

When I was a small child, four or five years old, I slept alone in my turret bedroom, as I do now. I had been tucked in by my nanny some hours earlier and had fallen asleep easily. I remember that I dreamed of ponies and rainbows. In the middle of the night, something woke me.

I don’t remember if it was a sound or a smell or some kind of subconscious feeling. I only know that I opened my eyes, my room illuminated by the faint glow of moonlight, and screamed. My closet door stood wide open. Creeping carefully across my room, its hooves tapping quietly on the hardwood floor, was a centaur.

At the time, of course, I didn’t know the creature by name. I only knew that a horse with the torso of a man was clomping toward me. And the look in his dark eyes left me with no doubt that he was not interested in making friends.

My scream startled him. I scrambled out of my four-poster bed, getting tangled up in the frilly lace ruffled bed skirt. Certain I would be easy prey, I looked up. Only to find my room empty.

Still terrified, I ran downstairs to the second-floor master bedroom. I burst through my parents’ door, flipped on the lights, and stood sobbing in the middle of the room.

“What is it, Greer?” Dad mumbled, half asleep.

“A-a-a monster!” I wailed.

My mother sat up in bed and called me closer. I was hoping for a hug and a kiss and maybe an invitation to sleep with them for once.

“Listen to me very carefully,” she said, making no move to touch me. “Monsters do not exist.”

“B-b-but—”

“No!” Her bark startled the fear right out of me. “Monsters. Don’t. Exist.”

I knew better than to argue again.

“You did not see a monster,” she insisted, calm once more. “And you will never see one again.”

Still shaking with fear, I nodded and backed away toward the door. Mother slid her sleep mask back into place. As I turned off the light, my dad mumbled, “Good night.”

I climbed the long, eerie staircase back up to my room. Standing outside my door, I took a deep breath. I told myself my mother was right, as she always was. Monsters did not exist. I hadn’t seen one that night, and I would never see one again.

After the series of hypnotherapy sessions Mother started me on the next day, I never did.

Now, considering what my sisters said, I almost wonder if maybe the centaur was not a figment of my imagination after all.

“Ludicrous.” The news of my adoption must have shaken me more than I realized, if I’m even pondering the possibility that mythological monsters actually exist, or that I might actually be a descendant of a hideous monster myself.

My phone rings in the hall.

“Thank goodness,” I say, relieved for the distraction.

Shoving thoughts of monsters and sisters and other nonsense from my mind, I straighten my spine and go answer the call. Even Veronica would be a welcome interruption at the moment.

“Greer Morgenthal.”

“Hey babe,” Kyle’s surfer-boy voice says. “What’s up?”

I close my eyes and mentally count to eleven. I’ve asked him not to call me “babe” more times than I can recall. I’m not sure if he thinks it’s charming or if the sun has actually cooked so many of his brain cells that he can’t remember I don’t like it. Either way, I’ve decided to ignore the transgression for the most part, and make him pay in other ways. Jewelry is always welcome.

The surfer-boy thing is mostly an act. He does surf, but not very well, and he’s the son of an internationally renowned oncologist and a tire heiress. He’s as likely to attend a benefit dinner in a tuxedo as he is to hit the surf in a wetsuit. It’s all about image.

“Hello, Kyle,” I answer, turning on girlfriend mode and trying to sound warm and affectionate. “I’m waiting for Henri to arrive with the petit fours for the tea and—”

“That’s great, babe,” he says, cutting me off. I’m about to forget my ignore-now-pay-later strategy when he asks, “How’d you feel about dinner at the Wharf tonight?”

I pause. “Where?” I ask cautiously. Last time we dined at the Wharf when he was in surfer-boy mode, we ate clam chowder from paper cups while standing at the end of the pier. I appreciate a good San Francisco chowder as much as the next Bay Area native, but standing up to eat is not my idea of a dinner date.

“Ahab’s,” he says.

I can hear the smile in his voice, like he knows he’ll impress me with his choice. And, to be honest, he has. Ahab’s is an iconic institution, and their cuisine is first-rate. Five stars. Their view is even better.

“Sounds delightful,” I reply, grinning to myself.

“Great,” he says. “Meet me there at seven?”

“Meet you—”

“Yeah, I’m at the beach with the guys.” Shouts echo in the background as the guys clamor to be heard. “Gotta go, surf’s up. See ya at seven, babe.”

Before I can say good-bye, he’s gone.

I set my phone down, close my eyes again, and remind myself of why I put up with Kyle. In the year we’ve been going out, I’ve gotten a lot of practice with what my personal trainer calls aggression-reduction techniques—an elaborate name for counting to ten. Or, in Kyle’s case, eleven.

He can be very sweet sometimes. Like last Valentine’s Day, when he skipped school to bring me two dozen red roses in French class, or when we drive down the coast and park on the beach, watching the sunset from the hood of his Jeep. Those days mostly make up for the other ones.

He’s also very handsome, in a lead-actor way. His brown hair is usually too long, but after he spends all summer surfing, the tips bleach to an amber gold that matches his tanned skin, making it hard for me to complain.

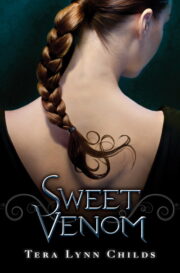

"Sweet Venom" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sweet Venom". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sweet Venom" друзьям в соцсетях.