It was important, more important than she could admit to anyone, that she leave a mark. She needed that to remind herself that she wasn't the weak and useless woman who had been so callously tossed aside.

Dripping with sweat, she picked up her water bottle and shovel and headed around to the front of the house again. She'd put in the first of the flowering almonds and was digging the hole for the second when a car pulled into the driveway behind her truck. Resting on her shovel, Suzanna watched Holt climb out.

She let out a little huff of breath, annoyed that her solitude had been invaded, and went back to digging.

“Out for a drive?” she asked when his shadow fell over her.

“No, the girl at the shop told me where to find you. What the hell are you doing?”

“Playing canasta.” She shoveled some more dirt. “What do you want?”

“Put that shovel down before you hurt yourself. You've got no business digging ditches.”

“Digging ditches is my business – more or less. Now, what do you want?”

He watched her dig for another ten seconds before he snatched the shovel away from her. “Give me that damn thing and sit down.”

Patience had always been her strong point, but she was hard – pressed to find it now. Working at it, she adjusted the brim of the fielder's cap she wore. “I'm on a schedule, and I have six more trees, two rosebushes and twenty square feet of ground cover to plant. If you've got something to say, fine. Talk while I work.”

He jerked the shovel out of her reach. “How deep do you want it?” She only lifted a brow. “How deep do you want the hole?”

She skimmed her gaze down, then up again. “I'd say a little more than six feet would be enough to bury you in.”

He grinned, surprising her. “And you used to be so sweet.” Plunging the shovel in, he began to dig. “Just tell me when to stop.”

Normally she repaid kindness with kindness. But she was going to make an exception. “You can stop right now, I don't need any help. And I don't want the company.”

“I didn't know you had a stubborn streak.” He glanced up as he tossed dirt aside. “I guess I had a hard time getting past that pretty face.” That pretty face, he noted, was flushed and damp and had shadows of fatigue under the eyes. It annoyed the hell out of him. “I thought you sold flowers.”

“I do. I also plant them.”

“Even I know that thing there is a tree.”

“I plant those, too.” Giving up, she took out a bandanna and wiped at her neck. “The hole needs to be wider, not deeper.”

He shifted to accommodate her. Maybe he needed to do a little reevaluating. “How come you don't have anybody doing the heavy work for you?”

“Because I can do it myself.”

Yes, there was stubbornness in the tone, and just a touch of nastiness. He liked her better for it. “Looks like a two – man job to me.”

“It is a two – man job – the other man quit yesterday to be a rock star. His band got a gig down in Brighton Beach.”

“Big time.”

“Hmm. That's fine,” she said, and turned to heft the three – foot tree by its balled roots. As Holt frowned at her, she lifted it, then set it carefully in the hole.

“Now I guess I fill it back in.”

“You've got the shovel,” she pointed out. As he worked, she dragged a bag of peat moss closer and began to mix it with the soil.

Her nails were short and rounded, he noted as she dug her already grimed fingers into the soil. There was no wedding ring on her finger. In fact, she wore no jewelry at all, though she had hands that were meant to wear beautiful things.

She worked patiently, her head down, her cap shielding her eyes. He could see the nape of her neck and wondered what it would be like to press his lips there. Heir skin would be hot now, and damp. Then she rose, switching on the garden hose to drench the dirt.

“You do this every day?”

“I try to take a day or two in the shop. I can bring the kids in with me.” With her feet, she tamped down the damp earth. When the tree was secure, she spread a thick lawyer of mulch, her moves competent and practiced. “Next spring, this will be covered with blooms.” She wiped the back of her wrist over her brow. The little tank top she wore had a line of sweat down the front and back that only emphasized her fragile build. “I really am on a schedule, Holt. I've got some aspens and white pine to plant out in back, so if you need to talk to me, you're going to have to come along.”

He glanced around the yard. “Did you do all this today?” “Yes. What do you think?”

“I think you're courting sunstroke.”

A compliment, she supposed, would have been too much to ask. “I appreciate the medical evaluation.” She put a hand on the shovel, but he held on. “I need this.”

“I'll carry it.”

“Fine.” She loaded the bags of peat and mulch into a wheelbarrow. He swore at her, tossed the shovel on top then nudged her away to push the wheelbarrow himself.

“Where out back?”

“By the stakes near the rear fence.”

She frowned after him when he started off, then followed him. He began digging without consulting her so she emptied the wheelbarrow and headed back to her truck. When he glanced up, she was pushing out two more trees. They planted the first one together, in silence.

He hadn't realized that putting a tree in the ground could be soothing, even rewarding work. But when it stood, young and straight in the dazzling sunlight, he felt soothed. And rewarded.

“I was thinking about what you said yesterday,” he began when they set the second tree in its new home.

“And?”

He wanted to swear. There was such patience in the single word, as if she'd known all along he would bring it up. “And I still don't think there's anything I can do, or want to do, but you may be right about the connection.”

“I know I'm right about the connection.” She brushed mulch from her hands to her jeans. “If you came out here just to tell me that, you've wasted a trip.”

She rolled the empty wheelbarrow to the truck. She was about to muscle the next two trees out of the bed when he jumped up beside her.

“I'll get the damn things out.” Muttering, he filled the wheelbarrow and rolled it back to the rear of the yard. “He never mentioned her to me. Maybe he knew her, maybe they had an affair, but I don't see how that helps you.”

“He loved her,” Suzanna said quietly as she picked up the shovel to dig. “That means he knew how she felt, how she thought. He might have had an idea where she would have hidden the emeralds.”

“He's dead.”

“I know.” She was silent a moment as she worked.

“Bianca kept a journal – at least we're nearly certain she did, and that she hid it away with the necklace. Christian might have kept one, too.”

Annoyed, he grabbed the shovel again. “I never saw it.”

She suppressed the urge to snap at him. However much it might grate, he could be a link. “I suppose most people keep a private journal in a private place. Or he might have kept some letters from her. We found one Bianca wrote him and was never able to send.”

“You're chasing windmills, Suzanna.”

“This is important to my family.” She set the white pine carefully in the hole. “It's not the monetary value of the emeralds. It's what they meant to her.”

He watched her work, the competent and gentle hands, the surprisingly strong shoulders. The delicate curve of her neck. “How could you know what they meant to her?”

She kept her eyes down. “I can't explain that to you in any way you'd understand or accept.”

“Try me.”

“We all seem to have some kind of bond with her – especially Lilah.” She didn't look up when she heard him digging the next hole. “We'd never seen the emeralds, not even a photograph. After Bianca died, Fergus, my greatgrandfather, destroyed all pictures of her. But Lilah...she drew a sketch of them one night. It was after we'd had a séance.”

She did look up then and caught – his look of amused disbelief. “I know how it sounds,” she said, her voice stiff and defensive. “But my aunt believes in that sort of thing. And after that night, I think she may be right to. My youngest sister, C.C. had an...experience during the séance. She saw them – the emeralds. That's when Lilah drew the sketch. Weeks later, Lilah's fiancé found a picture of the emeralds in a library book. They were exactly as Lilah had drawn them, exactly as C.C. had seen them.”

He said nothing for a moment as he set the next tree in place. “I'm not much on mysticism. Maybe one of your sisters saw the picture before, and had forgotten about it.”

“If any of us had seen a picture, we wouldn't have forgotten. Still, the point is that all of us feel that finding the emeralds is important.”

“They might have been sold eighty years ago.”

“No. There was no record. Fergus was a maniac about keeping his finances.” Unconsciously she arched her back, rolled her shoulders to relieve the ache. “Believe me, we've been through every scrap of paper we could find.”

He let it drop, mulling it over as they planted the last of the trees.

“You know the bit about the needle in the haystack?” he asked as he helped her spread mulch. “People don't really find it.”

“They would if they kept looking.” Curious, she sat back on her heels to study him. “Don't you believe in hope?”

He was close enough to touch her, to rub the smudge of dirt from her cheek or run a hand down the ponytail. He did neither. “No, only in what is.”

“Then I'm sorry for you.” They rose together, their bodies nearly brushing. She felt something rush along her skin, something race through her blood, and automatically stepped back. “If you don't believe in what could be, there isn't any use in planting trees, or having children or even watching the sun set.”

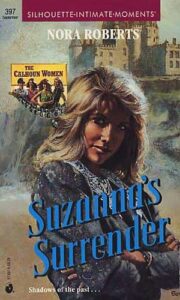

"Suzanna’s Surrender" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Suzanna’s Surrender". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Suzanna’s Surrender" друзьям в соцсетях.