Thirty minutes later, he replaced the gun. His face was set, his eyes flat and hard. His grandfather's canvases had been moved, not much, but enough to tell Holt that someone had touched them, studied them. And that was a violation he couldn't tolerate.

Whoever had tossed the place had been a pro. Nothing had been taken, little had been disturbed, but Holt was certain every inch of the cottage had been combed.

He was also certain who had done the combing. That meant that Livingston, by whatever guise he was using, was still close. Close enough, Holt thought, that he had discovered the Bradford connection to the Calhouns. And the emeralds.

Now, he decided as he dropped a hand on the head of the dog who whined at his feet, it was personal.

He went through the kitchen door to sit on the porch with his dog and a beer and watch the water. He would let his temper cool and his mind drift, sorting through all the pieces of the puzzle, arranging and rearranging until a picture began to form.

Bianca was the key. It was her mind, her emotions, her motivations he had to tap into. He lit a cigarette, resting his crossed ankles on the porch rail as the light began to soften and pearl toward twilight.

A beautiful woman, unhappily married. If the current crop of Calhoun women were anything to go by, Bianca would also have been strong willed, passionate and loyal. And vulnerable, he added. That came through strongly in the eyes of the portrait, just as it came through strongly in Suzanna's eyes.

She'd also been on the upper rungs of society's ladder, one of the privileged. A young Irishwoman of good family who had married extremely well. Again, like Suzanna.

He drew on the cigarette, absently stroking Sadie's ears when she nuzzled her head into his lap. His gaze was drawn toward the little yellow bush, the slice of sunshine Suzanna had given him. According to the interview with the former maid, Bianca had also had a fondness for flowers.

She had had children, and by all accounts had been a good and devoted mother, while Fergus had been a strict and disinterested father. Then Christian Bradford had come into the picture.

If Bianca had indeed taken him as a lover, she had also taken an enormous social risk. Like Caesar's wife, a woman in her position was expected to be unblemished. Even a hint of an affair – particularly with a man beneath her station – and her reputation would have been in tatters.

Yet she had become involved.

Had it all grown to be too much for her? Holt wondered. Had she been eaten up by guilt and panic, hidden the emeralds away as some kind of last ditch show of defiance, only to despair at the thought of the disgrace and scandal of divorce. Unable to face her life, she had chosen death.

He didn't like it. Shaking his head, Holt blew out a slow stream of smoke. He just didn't like the rhythm of it. Maybe he was losing his objectivity, but he couldn't see Suzanna giving up and hurling herself onto the cliffs. And there were too many similarities between Bianca and her greatgranddaughter.

Maybe he should try to get inside Suzanna's head. If he understood her, maybe he could understand her star – crossed ancestor. Maybe, he admitted with a pull on the beer, he could understand himself. His feelings for her seemed to undergo radical changes every day, until he no longer knew exactly what he felt.

Oh, there was desire, that was clear enough. But it wasn't simple. He'd always counted on it being simple.

What made Suzanna Calhoun Dumont tick? Her kids, Holt thought immediately. No contest there, though the rest of her family ran a dead heat. Her business. She would work herself ragged making it run. But Holt suspected that her thirst to succeed in business doubled right back around to her children and family.

Restless, he rose to pace the length of the porch. A whippoorwill came to roost in the old wind – bent maple and lifted its voice in its three – note call. Roused, the insects began to whisper in the grass. Hie first firefly, a lone sentinel, flickered near the water that lapped the bank.

This, too, was something he wanted. The simple quiet of solitude. But as he stood, looking out into the night, he thought of Suzanna. Not just the way she had felt in his arms, the way she made his blood swim. But what it would be like to have her beside him now, waiting for moonrise.

He needed to get inside her head, to make her trust him enough to tell him what she felt, how she thought If he could make the link with her, he would be one step closer to making it with Bianca.

But he was afraid he was already in too deep. His own thoughts and feelings were clouding his judgment. He wanted to be her lover more than he had ever wanted anything. To sink into her, to watch her eyes darken with passion until that sad, injured look was completely banished. To have her give herself to him the way she had never given herself to anyone – not even the man she had married.

Holt pressed his hands to the rail, leaned out into the growing dark. Alone, with night to cloak him, he admitted that he was following the same pattern as his grandfather.

He was falling in love with a Calhoun woman.

It was late before he went back inside. Later still before he slept.

Suzanna hadn't slept at all. She had lain awake all night trying not to think about the two small suitcases she had packed. When she managed to get her mind off that, it had veered toward Holt. Thoughts of him only made her more restless.

She'd been up at dawn, rearranging the clothes she'd already packed, adding a few more things, checking yet again to be sure she had included a few of their favorite toys so that they wouldn't feel homesick.

She'd been cheerful at breakfast, grateful that her family had been there to add support and encouragement. Both children had been whiny, but she'd nearly joked them out of it by noon.

By one, her nerves had been frayed and the children were cranky again. By two she was afraid Bax had forgotten the entire thing, then was torn between fury and hope.

At three the car had come, a shiny black Lincoln. Fifteen horrible minutes later, her children were gone.

She couldn't stay home. Coco had been so kind, So understanding, and Suzanna had been afraid they would both dissolve into puddles of tears. For her aunt's sake as much as her own, she decided to go to work.

She would keep herself busy, Suzanna vowed. So busy that when the children got back, she hardly would have noticed they'd been gone.

She stopped by the shop, but Carolanne's sympathy and curiosity nearly drove her over the edge.

“I don't mean to badger you,” Carolanne apologized when Suzanna's responses became clipped. “I'm just worried about you.”

“I'm fine.” Suzanna was selecting plants with almost obsessive care. “And I'm sorry for being short with you. I'm feeling a little rough today.”

“And I'm being too nosy.” Always good – natured, Carolanne shrugged. “I like the salmon – colored ones,” she said as Suzanna debated over the group of New Guinea impatiens. “Listen, if you want to blow off some steam, just call me. We can have a girls' night out.”

“I appreciate that.”

“Anytime,” Carolanne insisted. “It'll be fine. That's a really nice grouping,” she added as Suzanna began to load her choices into the truck. “Are you putting in another bed?”

“Paying off a debt.” Suzanna climbed into the truck, gave a wave then drove off. On the way to Holt's, she busied her mind by designing and redesigning the arrangement for the flower bed. She'd already scouted out the spot, bordering the front porch so he could enjoy it whenever he came or went from the cottage. Whether he wanted to or not.

The job would take her the rest of the day, then she would unwind by walking along the cliffs. Tomorrow she would put in a full day at the shop, then spend the cool of the evening working the gardens at The Towers.

One by one, the days would pass.

She didn't bother to announce herself after she'd parked the truck, but set right to work staking out the bed. The result was not what she'd hoped for. As she dug and hoed and worked the soil there was no soothing response. Her mind didn't empty of worries and fill with the pleasure of planting. Instead a headache began to work nastily behind her eyes. Ignoring it, she wheeled over a load of planting medium and dumped it. She was raking it smooth when Holt stepped out.'

He'd watched her from the window for nearly ten minutes, hating the fact that the strong shoulders were slumped and her eyes dull with sadness.

“I thought you were taking the day off.”

“I changed my mind.” Without glancing up, she rolled the wheelbarrow back to the truck and loaded it with flats of plants.

“What the hell are all of those?”

“Your paycheck.” She started with snapdragons, delphiniums and bright shasta daisies. “This was the deal.”

Frowning, he came down a couple of steps. “I said maybe you could put in a couple of bushes.”

“I'm putting in flowers.” She packed down the soil. “Anyone with an ounce of imagination can see that this place is crying for flowers.”

So she wanted to fight, he noted, rocking back on his heels. Well, he could oblige her. “You could have asked before you dug up the yard.”

“Why? You'd just sneer and make some nasty macho remark.” He came down another step. “It's my yard, babe.”

“And I'm planting flowers in it. Babe.” She tossed her head up. Yeah, she was mad enough to spit nails, he noted. And she was also miserable. “If you don't want to bother to give them any water or care, then I will. Why don't you go back inside and leave me to it?”

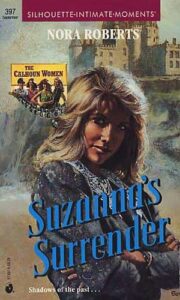

"Suzanna’s Surrender" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Suzanna’s Surrender". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Suzanna’s Surrender" друзьям в соцсетях.