“Why don’t you use your own mirror? Seriously. We’re not poor, you could buy yourself a full-length mirror.”

Zoe never let Penny get her angry. She said, “Because I like your mirror better. It makes my ass look smaller.”

How many times had Hobby complained to his mother about Penny? “She drives me crazy,” he would say. “Why can’t she just relax like a normal human being?”

“Her heart is made from the finest bone china,” Zoe would answer. “Like a teacup.” And then Zoe would smile, and so would Hobby.

On Penny’s dresser was her paddle brush, filled with long, dark hairs. She used to keep it in the bathroom, but Hobby had protested when he found one of Penny’s hairs wound through the bristles of his toothbrush. There was her fancy perfume atomizer, which had never held a drop of perfume. There was her jewelry box made from bird’s-eye maple. Hobby opened it. He sorted through friendship bracelets woven out of embroidery thread, her real gold hoop earrings, her pearl on the gold chain that had been their grandmother’s, her pin from the National Honor Society, and a sea-foam-green box from Posh that contained a pair of silver dangly earrings edged in chips of blue sapphire. Jake had bought her those earrings for their two-year anniversary.

Hobby opened the top drawer of Penny’s dresser and found himself staring into a tangle of lacy underwear. Okay, embarrassing. He quickly shut the drawer, but as he did, he caught a glimpse of the edge of something red and shiny. A book. A journal. He nudged aside the lacy things to confirm that what he was looking at was the red leather cover of a journal. He flipped through the pages to make sure it was Penny’s handwriting-loopy and girlish-then he put the journal back and shut the drawer again. Original, Pen, hiding your journal in your underwear drawer, he thought. I found it in the first place I looked.

The shade on the window was flapping in the breeze. Hobby inspected Penny’s bedside table. There was a glass of water, evaporated down to an inch or so, with a film of dust across the top. A box of Kleenex. A copy of Moby-Dick, which Penny referred to as her independent reading. She’d been telling people this for at least nine months, but when Hobby checked now, he saw that she had read only up to page 236. She had died without even getting halfway through.

From the bedside table, Hobby could pivot and open Penny’s closet. On the inside of the door was a cork board displaying a photo montage of Penny and Jake. Penny and Jake in Guys and Dolls, Penny and Jake in Damn Yankees, Penny and Jake in Grease. Penny and Jake in the stands at one of Hobby’s football games, Jake carrying Penny down the beach on his back, Penny and Jake with marshmallows in their mouths, Penny and Jake at the prom. There was also a picture of himself and Penny on Christmas morning in front of the tree, Penny in some ridiculous high-necked flannel nightgown that made her look like Laura Ingalls Wilder, her hair in braids to heighten the effect, and him in boxers and one of his father’s vintage Clash T-shirts (his mother had kept his father’s concert T-shirts, and she gave Hobby one every year on his birthday). In this Christmas photo, Penny was beaming and apple-cheeked, and Hobby was bleary-eyed and scowling. It was this past Christmas. Penny had woken him up at seven-thirty. He would have been content to sleep until noon and then eat three quarters of his mother’s Christmas coffee cake and then open his stocking. But not Penny. She had been a freaking Christmas elf.

And that’s it for you and Christmas, Pen, Hobby thought. Maybe for all of them and Christmas. His mother had already talked about taking a trip to St. John at the holidays.

Penny’s clothes were hanging in the closet. His mother had said something about Goodwill, when she got around to it. Hobby fingered Penny’s favorite blue blouse, which had cost a fortune-two or three hundred dollars. Penny had seen it on line, she wanted to buy it with her own money, but Zoe said no, there was no reason for a teenager to spend that kind of money on one article of clothing. And then a few weeks later, Penny had been asked to sing in front of the Boston Pops for the second year in a row, personally, by Keith Lockhart, and Zoe had bought Penny the blouse for the occasion. Hobby touched the silky material. The blouse was still here, but Penny wasn’t. It was messing with his head.

He hopped over to the edge of her bed. Her poster of Robert Pattinson was still hanging, her Twilight books were still on the shelves. Below her books were CDs-Charlotte Church and Jessye Norman next to Puccini’s operas next to Send In the Clowns by Judy Collins. Certainly Penelope Alistair was the only seventeen-year-old in the world to own a Judy Collins CD. That was truly the music she liked best, however: those godawful songs of the 1970s. Crystal Gayle, Anne Murray, Karen Carpenter. It was Penny’s dream to become one of these women. By the time she was “grown up”-say, in 2015-she figured the world would be ready to hear these songs again. If Penny ever made it onto American Idol, she planned to sing Debby Boone’s “You Light Up My Life.” She used to sing it all the time in the shower.

“Even your voice can’t save that song,” Hobby said. “Pick something else.”

“I’m afraid I have to agree with your brother,” Zoe said. Zoe had good taste in music. She was a Deadhead. She had a cardboard box with all of her bootleg tapes stashed under her bed. And she liked modern stuff, too-Eminem, Spoon, Rihanna.

But Penny continued to sing “You Light Up My Life.” And the soundtrack to Fame. Hobby would have laughed if it hadn’t been so tragic.

He closed the door to the closet. Penny had a drafting table instead of a desk, just as Hobby did in his room. Hobby had a drafting table because he wanted to be an architect; Penny had one because she was a copycat. She kept a sketchpad and a box of colored pencils on her drafting table because she liked to “draw,” though she wasn’t much of an artist. But now Hobby stared at the sketchpad, wondering if his sister had left behind some sort of note. He had gathered-though no one had said it to him directly-that certain people thought the accident had been a suicide.

Hobby crutched his way over to the drafting table. If there was a note, he would have to show his mother. If it turned out that Penny had committed suicide, he was going to boil over in anger.

But the sketchpad was blank, except for a heart drawn in black pencil. A heart she was probably planning on filling with Penny + Jake, TL4EVA. It was something of a joke around school that Penny had graffitied every pair of jeans that Jake Randolph owned.

She would have been really upset to hear about Jake and Winnie. She would have done something drastic, maybe.

No suicide note. That was good. Hobby wondered if his mother had already been in here panning for one. She must have, right? Immediately afterward? But maybe not. This place looked untouched.

Hobby was about to vacate the premises. He couldn’t shake the feeling that Penny was watching him. “Matter cannot be created or destroyed”-so she existed somewhere, right? She would not like the idea of Hobby’s hobbling around her room on his crutches, poking through her stuff. So he would go.

But who was he kidding? He wasn’t leaving without the journal. He moved over to the dresser and, without looking at himself in the mirror, slipped the journal out from under Penny’s underwear. Then he lumbered out into the hallway and shut the door.

Wherever she was, she would not want him reading her journal. But what had Zoe said? “Sorry, Hob, I’m human.” Yep, Hobby got it. He thought, Sorry, Pen, I’m human. I can’t pass up the chance to read it.

None of the entries were dated, so Hobby had to orient himself based on content. The journal seemed to start a few years earlier because it referenced Mrs. Jones-Crisman, who had been Penny’s homeroom teacher during freshman year. In the very first entry, Mrs. J-C calls her out for kissing Jake in the hallway. In the next entry, Penny has a fight with Zoe because she kissed Jake in the backseat of the Karmann Ghia. Zoe said, “I don’t get paid enough to listen to the two of you swapping spit. Do it in private.”

Like where? Penny wondered in her journal. If I can’t kiss him at school and I can’t kiss him in the car, where am I going to kiss him?

Hobby worried that the whole thing was going to be about kissing Jake. And it was, for the most part-at least at first. Penny wrote about every time she made out with Jake; she compared kissing him to “eating something really delicious and you don’t want to stop. Like Mom’s apple fritters with the Bavarian cream.”

Hobby stopped. It was too bad Jake was in Australia. He would have appreciated that his kissing was on par with Zoe’s apple fritters. Hobby would have laughed at this himself if it hadn’t been so tragic.

He skipped ahead. He didn’t want to read about Penny’s getting felt up, or Penny’s discovering Jake’s erection. (He accidentally stumbled across the line Do you feel yourself change when we do this?) He didn’t want to read about Penny’s argument with her voice coach. He was looking for something better, more interesting.

He thought, Come on, Pen, give me something I can work with.

And then, two thirds of the way through the journal, the tone changed. Penny started referring to everyone by their first initials only. Jake became J. Hobby found references to himself and his mother: H at practice, Z at work. J and I home alone but I don’t want to, I can’t explain it, I just don’t feel like it. I’m too sad. Sad about what? J asks me. He wants me to have a reason so he can fix it. But I don’t have a reason. I’m just sad, and sad isn’t even the right word. I’m empty. Since I don’t have a reason, J applies his own reason: hormones.

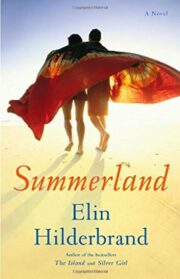

"Summerland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Summerland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Summerland" друзьям в соцсетях.