“I love you twice as much as any other mother loves her child,” she’d sworn to her once.

Penny’s body had been as familiar to Zoe as her own. How was it possible that she would never hold that body again? The answer was, it wasn’t possible. In which case Hobby was right: they could live only in some sort of suspended state of delusion, certain that Penny would someday be returned to them.

Dorenda said, “That was a lovely piece in the paper.”

“It was,” Zoe agreed, though she hadn’t actually read it. She had, at Hobby’s insistence, sent some photographs to the newspaper, but she hadn’t been able-forgive her-to face reading the article about her dead daughter. She had folded the piece and saved it in a drawer. Down the road, maybe, when she was better equipped for it emotionally than she was now, she would take it out and read it.

“And how about the white cross?” Dorenda said. “I had Philip drive me down so I could see it for myself.”

“Cross?” Zoe said. Her automatic response to anything even vaguely religious was one of severe allergy, falling just short of anaphylactic shock. “What cross?”

“The big one at the end of the road,” Dorenda said. “Where the girls have been singing.”

Zoe tilted her head.

Dorenda said, “You haven’t seen the cross?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Oh,” Dorenda said. For a second she seemed embarrassed. “Well, it’s hardly a secret. There’s a seven-foot cross at the end of Hummock Pond Road. And the girls from the madrigal group gather there to sing each night at sunset. It’s a tribute to Penny.”

Zoe asked, “Who built the cross?”

“I don’t know,” Dorenda said. “One of the girls’ fathers must have. It’s just two boards nailed together. But there are bouquets of flowers at the base and ribbons fluttering around it, things like that.”

Zoe bent her head. Dorenda Allencast laid a feather-light hand on her back. Dorenda probably thought she was overcome with emotion at the beauty of the gesture. But what Zoe felt like shouting was that there shouldn’t be a tribute unless she said there should be a tribute. A seven-foot cross? Bouquets? Girls from the Nantucket Madrigals singing every night at sunset? What Zoe thought was, She was my daughter! How can anyone’s grief matter but mine? This was a horrible, awful, ungenerous thought. Penny’s death was turning her into a small, mean person.

That night, on her way home from work, Zoe drove out to the end of Hummock Pond Road to look at the cross. It was visible from two hundred yards away, even in the dark. Its white arms reached up from the sand like a ghost’s. Zoe parked her car and got out. The night was warm enough, finally, that she didn’t need a jacket, but her hands were ice-cold. Here she was, in the spot where it had happened. The cross must mark the point of impact.

The cross was as white as bone. As Dorenda promised, there were bouquets of flowers at the base, and satin ribbons wound around it that reminded Zoe of a maypole without, however, doing much to ameliorate the stark religious significance of the cross itself. The cross meant what? she wondered. That a soul had departed from this spot? A girl was driving too fast, and then she crashed the car and died.

Part of Zoe wanted to pinpoint exactly who was responsible for constructing the cross, who had painted it, which father had loaded it into the back of his pickup truck and driven it down here. Who had erected it? Whose idea had the singing been? But Zoe guessed that it had been a collective effort by the girls, Penny’s friends and acquaintances, who wanted to make a statement dramatic enough to match their overwhelming emotions. A girl they had grown up with, had known and loved, had admired and looked up to, had died.

She existed for more than just me, Zoe thought. For more than me and Hobby.

Penny had been part of a class, a school, a community. Other people wanted to pound a cross into the ground for her, sing for her, publish a valediction in the newspaper for her. Who was Zoe to tell them they couldn’t? She didn’t like it because it made her feel as if there were less of Penny to claim. She needed Penny all to herself. She was mine, she thought. Mine.

Selfish, horrible thoughts, but there you had it. They were real.

She was too spooked by the cross to stick around for very long. She thought maybe she should do something, throw a rock at it or kiss it or kick it or cry in front of it, but none of those things felt right.

She climbed into her car and turned the key. It was nearly nine o’clock. She needed to get home to Hobby. But she sat for a second, staring at the ocean. Over the course of a single day she had gone back to work and then had come to look at the cross. These things seemed noteworthy. She wished there were someone she could tell.

But there was only one answer to that: Jordan.

Jordan, Jordan, Jordan. Zoe didn’t have the strength to think about Jordan. But she couldn’t stop thinking about him, either.

There was that night during Christmas Stroll, the two of them embracing up against Jordan’s car, which they later referred to as “the moment.” The moment when they knew.

Nothing happened after that. The next time they saw each other was in early January. They were in a crowded gym, at a middle school basketball game in which Hobby scored 28 points. Jordan walked in with his notepad. Sitting down next to Zoe, he told her that he’d come to report on the game.

She asked, “You’ve been demoted?”

He said, “My sportswriter quit.”

She said, “You spell our last name A-L-I-S-T-A-I-R.”

He said, “Yes, I know how to spell your name.”

And in this way everything returned to normal. The night in the new December snow was tucked away somewhere deep inside Zoe. She was sure that Jordan treasured that night also, but she was equally sure they would never speak of it again.

Fast forward: June 29, not of that year but of the following one. The twins were fifteen years old. Zoe traveled to Martha’s Vineyard to watch Hobby play baseball in the Cape and Islands All-Star Tournament. She had reserved a room at the Charlotte Inn as a treat for herself and Penny. She knew that booking such lavish accommodations made her seem snooty (the rest of the parents were staying up the street at the Clarion), but she had been doing this All-Star thing since Hobby was nine years old, and she was tired of weekends away that included overly chlorinated indoor pools and communal “dinners” consisting of bad pizza and margaritas from a can. She still had some of the money left to her by her parents, though she didn’t broadcast that fact; she constantly had to reassure herself that it was nothing to be ashamed of. She was going to get a nice room for her and her daughter, and they were going to have a nice dinner. Let the other parents talk.

But then Penny didn’t come with her. Annabel Wright was having a birthday, and her parents had gotten tickets to see Mamma Mia in Boston and invited Penny to go.

Even better, Zoe thought guiltily. She would luxuriate in the room at the Charlotte Inn all by herself. She would light candles and read in the clawfoot tub. She would order room service from L’Etoile. She would sleep naked between the luscious 1000-thread-count sheets.

She thoroughly enjoyed step one: she soaked in the peony-scented water and read the final chapters of John O’Hara’s Appointment in Samarra by the light of three beeswax tapers that she’d asked the front desk to place in her room. She washed the dust and the sweat of the ball field off her skin and took breaks between pages to remember Hobby on the mound, the lean, graceful form of him throwing fire at the alternately eager and fearful batters from Harwich, South Plymouth, and the Vineyard. Nantucket had won all three games for the first time in its forty-year history of playing in the Little League. Hobby had pitched a no-hitter, and over the course of the three games he had gone nine for twelve as a batter, including two home runs. After each game Zoe had watched her son accept handshakes from the coaches of the other teams. She studied Hobby closely: he was grinning but not gloating. He was a good kid. Zoe imagined him at that very minute devouring spare ribs and potato salad at a barbecue with the other teams. He was spending the night with the family of the Vineyard’s first baseman, in Oak Bluffs.

As Zoe climbed out of the tub and reached for her waffled robe, her cell phone rang. Penny, she thought, calling to tell her about the musical. But when she looked at the display, she saw it was Jordan.

“Hey,” she said. “I’m on the Vineyard.”

“I know,” he said. “I am too.”

“You are?” she said.

He told her he had come over that afternoon for a fund raiser for a Democratic congressional candidate-Kirby Callahan, Zoe knew of him-and that afterward he’d met Joe Bend, the publisher of the Vineyard Gazette, at the Navigator for drinks, which had turned into a sail on Joe’s sloop. Jordan had then headed to the airport to catch the six-thirty plane, but he’d missed it. So now he was stuck.

“You’re at the airport?” Zoe asked. She checked the clock in her room. It was five minutes past seven.

“Turns out that was the last plane,” he said. “So I’m at the Wharf Pub.”

“In Edgartown?” Zoe said. It was right down the street.

“Come meet me,” he said. He sounded drunk, which was novel. He always drank beer and water side by side so as not to get “carried away,” and he always limited himself to two beers. On special occasions he might have a third beer, but by “special occasion” he meant Christmas, or the Super Bowl. At dinner parties he had one glass of wine.

“Um,” she said. The menu for L’Etoile was spread open on the bed. Zoe had already decided on a bottle of the Cakebread chardonnay, the prosciutto-wrapped watermelon and haloumi cheese appetizer, the softshell crab entree, and the grilled pineapple with macadamia crunch ice cream for dessert. Was she supposed to give all that up?

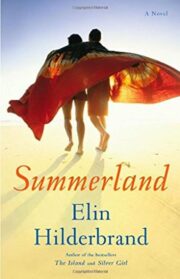

"Summerland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Summerland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Summerland" друзьям в соцсетях.