Demeter: “Really?”

Lynne: “She sounded desperate. But I told her you were working for Frog and Toad now and might be too tired to work at night…”

So her mother had provided her with an out. Demeter could say no. But if she said no, would it seem as if she were avoiding the Kingsleys? She had never turned Mrs. Kingsley down before. And her old logic still reigned: babysitting on a Saturday night was far superior to staying home alone on a Saturday night.

Demeter left two bites of steak untouched and turned down the offer of blackberry pie with homemade whipped cream. Instead she went to the phone and called Mrs. Kingsley back and said that yes, certainly she could babysit on Saturday night. Mrs. Kingsley sounded like her grateful, happy self, utterly relieved that despite the tragic events of graduation night, she hadn’t lost her most reliable babysitter.

“Seven o’clock?” Mrs. Kingsley said.

“See you then,” Demeter said. She hung up the phone, thanked her mother for dinner, got herself a tall glass of ice, and retreated to her bedroom.

At six forty-five on Saturday night, Demeter was driving her Escape on Miacomet Road toward Pond View, which was where the Kingsleys lived, when she saw something moving up ahead. At first she wasn’t sure if it was one person or two-the sun was descending, shining right into her eyes-and then she saw that it was two: a low, squat figure with a taller figure behind. It was Zoe Alistair pushing Hobby in his wheelchair, heading in her direction.

Demeter hit the brakes so hard she bucked in her seat. What to do? She knew the three Fs of threatened animal behavior: Freeze, Flee, or Fight. Freezing, which was her first instinct, wouldn’t be effective; she couldn’t just sit in her car in the middle of the road. So she would flee, turn the car around and hide out on Otokomi Road until Zoe and Hobby rolled past. But that could take a while; they weren’t going very fast, and Demeter didn’t want to be late for Mrs. Kingsley.

Demeter pulled down the eye shade and adjusted her Ray-Bans. She would simply drive past them. She knew they would recognize her car: Zoe, Penny, and Hobby had all been at her sixteenth-birthday “party,” when Al Castle had presented it to her, tied up with a big red bow. Demeter had given Penny and Hobby a ride around the neighborhood in it, and Hobby had played with the sunroof and asked questions about the gas mileage. Penny had said, “Hobby wants his own car so bad.” So bad, and yet he had never made a move toward getting his license.

Demeter stepped lightly on the gas, and the car inched forward, closing in on the two approaching figures. Demeter tried to decide what to do. She hadn’t heard from Hobby since his return from the hospital, and she counted this as a good thing. He didn’t have probing questions to ask her about what had happened in the dunes, as Jake did. The shameful thing was that Demeter hadn’t called either Hobby or Zoe to offer her condolences. She just couldn’t. Did they understand why she couldn’t? She had been right there, an integral part of it all, and their families had so much history together, and for both of those reasons, she couldn’t just call and say she was sorry, the way the rest of the island had done.

Should she wave and breeze on by? That was a hideous notion; to wave would be to acknowledge their presence, while at the same time letting them know that they weren’t important enough for her to stop and talk to. She should stop. She should… say something. This was a sign from above, this random encounter with no one else around, and for the first time in days, Demeter was sober. She hadn’t had a drink since the night before-well, that wasn’t true, she had done a shot of vodka at ten o’clock that morning to stop the uncontrollable shaking of her hands, but that was all. She wanted to be sober and alert for Mrs. Kingsley and the three Kingsley children.

Demeter got closer, close enough to see that Hobby had his arm in a sling and his leg in a cast and that half his head was shaved. Zoe was pale, and her hair was flat. Zoe was saying something to Hobby, and Hobby was craning his neck to look at her. Demeter, coward that she was, took this opportunity to step on the gas and cruise right past them, her mouth set tight, without giving them a wave or a glance or anything.

She wondered if they were turning around in disbelief, asking each other, “Was that Demeter who just drove by?” She didn’t check her rearview mirror; she just kept driving with a mounting sense of relief. She had escaped a painful and difficult situation. This relief was quickly followed by man-eating guilt. It was all her fault. She could tell herself that it was Penny who had flipped out, Penny who had been driving the car, Penny who had put their safety in peril. But it didn’t take away her certainty that she, Demeter, was to blame.

She had had the best intentions for the evening, but the sight of Zoe and Hobby toppled her like a house of cards. Demeter hurried the night along: she put the three Kingsley children in the bathtub, then handed them towels and clean pajamas. She offered them each a bribe of two Oreo cookies and half a glass of milk in exchange for an earlier bedtime. She supervised teeth brushing and read them a chapter from Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix in such a way that she heard herself saying the words aloud even though her mind was elsewhere. She was back on Miacomet Road, watching Zoe push her son in his wheelchair along the edge of the pond, pointing out wild irises or red-winged blackbirds or this house or that house where she had catered a fancy party. Or perhaps they were talking about Penny-how she had been crazy about chocolate-chip cookie dough but not about chocolate-chip cookies, or how she had prayed for snow so she could go sledding in Dead Horse Valley, flat on her back on the ancient Radio Flyer that Zoe had bought at a yard sale. If she didn’t become a professional singer, Penny used to say, she wanted to be an Olympic luger.

Demeter’s leg was twitching as she lay between Lyle and Barrett Kingsley. She had to get downstairs. Before she left (Mr. Kingsley had not been around, and his absence had not been addressed), Mrs. Kingsley had said those fateful words that Demeter both longed and dreaded to hear: “Help yourself to anything you want.” Demeter checked to see how many pages were left in the chapter. Three.

Demeter thought about Zoe. She thought, I am to blame, but no one is innocent in this. She thought, It’s worse to be the mother of the hurt person than the hurt person herself.

She kissed the Kingsley children good night (she had missed them), and then she hurried downstairs. The sun had set, the house was darkening, and despite the late-hour injection of chocolate into the children’s bloodstreams, they were quiet upstairs.

Stillness.

“Help yourself to anything you want.” The pantry, as usual, was filled with bags of barbecue-flavor Fritos and Funyuns and pretzels and cheese curls; there were boxes of crackers and cookies and cherry hand pies. The fridge held dips and cheeses and salamis and containers of broccoli slaw and lobster salad from Bartlett’s Farm.

But food no longer appealed to Demeter. “Help yourself to anything you want.” She couldn’t possibly pour herself a drink, she thought, not after what had happened. But she found herself powerless. She opened the Kingsleys’ bar and discovered a brand-new bottle of Jim Beam sitting in the exact same place where the other one had been. This spooked Demeter; she shut the liquor cabinet. She went to the freezer and pulled out a frosty bottle of Ketel One. The shaking had returned to her hands, but this might be due to anticipation, she realized. She brought the bottle to her lips and drank until her eyes watered and the vodka burned the lining of her throat. She gasped for breath.

Zoe Alistair had looked… well, she had looked ruined. The strange thing was that Demeter’s mother hadn’t said a word about Zoe in weeks. To Demeter’s knowledge, Lynne Castle hadn’t seen or spoken to Zoe since that night at the hospital, though she still maintained tight control over the dropoff dinner schedule.

Demeter took another pull off the vodka bottle. The reassuring feeling returned: everything was going to be okay. She poured three fingers of vodka into a juice glass and added ice. It looked just like water. She would drink just this much, and then she would be done.

Just as she brought the drink to her lips, she heard the mudroom door slam, and she nearly dropped the glass on the floor. She set it down on the counter and whipped around in time to see Mr. Kingsley breeze in. He was sweaty, wearing white shorts and a white polo shirt and carrying a tennis racquet. He seemed as stunned to see Demeter as she was to see him.

“Hey!” he said. He squinted at her and smiled, and she thought, I’ve babysat for these people for five years, and he’s forgotten my name.

“Hey, Mr. Kingsley,” she said. Her head was spinning from the vodka. If he discovered what was in her glass, her life was over. But Demeter felt strangely calm. There was something about Mr. Kingsley that she recognized immediately, something in his demeanor, in the way he was swaying while standing still: he was drunk. He threw his tennis racquet to the floor with a clatter, and Demeter instinctively looked up the stairs, to where the children were sleeping.

“Demeter,” Mr. Kingsley said, as if her name were a tricky crossword-puzzle clue that he had just figured out. “You poor thing, you.” He took a step forward, then stopped. “Is Mrs. Kingsley home?”

“No,” Demeter said. “She left at seven for a… cocktail party in Sconset, I think?”

“Right,” Mr. Kingsley said with an exaggerated nod. “I’m supposed to meet her there. I just got held up at the club.”

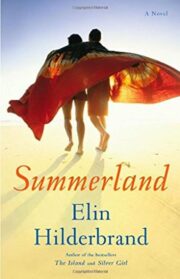

"Summerland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Summerland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Summerland" друзьям в соцсетях.