He swung his legs to the floor. Ava was sleeping in Ernie’s nursery with her earplugs in and the white-noise machine going, and the door locked and the shades pulled. And the magic elixir of her nightly Ambien silencing her demons. She would be completely dependent on him to rescue her in the event of a fire.

Fire? he thought.

And then he remembered: graduation.

He raced to the phone. The caller ID read Town of Nantucket. Which meant the police, or the hospital, or the school.

“Hello?” Jordan said. He tried to sound alive, awake, in control.

“Dad?”

That was the only word Jake was able to say. What followed was blubbering, but Jordan was buffered by the knowledge that Jake was alive, he could talk, he had remembered the phone number for the house.

A policeman came on the line. Jordan knew many of the officers but not all of them, and especially not the summer hires.

“Mr. Randolph?” the officer, his voice unfamiliar, said. “Sir?”

ZOE

She had flaws, yes she did. What would be the worst? There was the obvious thing, but she would set that aside for a moment. She would travel back to before her love affair with Jordan Randolph. What had been her faults before? She was selfish, self-absorbed, self-centered-but really, wasn’t everyone? She occasionally-but only occasionally-had put her own happiness before the happiness of the twins. There was the time she had left Hobby and Penny with the Castles and flown to Cabo San Lucas for a week. She had convinced herself, and Al and Lynne Castle, that she was suffering from Seasonal Affective Disorder. She had lied to Lynne and claimed that an off-island doctor, the mythical “Dr. Jones,” had actually “diagnosed” her with SAD and “prescribed” the trip to Cabo. The lie had been unnecessary; Lynne said she understood, and Zoe deserved a week away, and it would be no trouble at all for her to take care of the twins. Lynne didn’t know how Zoe did it, raising the two of them on her own.

The trip to Cabo had been a onetime thing. (It shimmered in Zoe’s memory: the chaise longue by the edge of the infinity pool, the scallop ceviche and mango daiquiris, and the twenty-seven-year-old desk clerk whom she had easily seduced and slept with five out of the seven nights.) Had she felt any guilt about leaving her children that week? If she had, she couldn’t remember it. And yet in that moment when they both rushed into her arms, shrieking with happiness at her return, she swore she would never leave them again. And she had kept her word.

There had, however, been nights when Zoe opened a bottle of good white Burgundy and watched six episodes of The Sopranos in one sitting while the children ate cereal for dinner and put themselves to bed. There had been other times when Zoe lost her temper with the twins for no reason other than that they were two complex creatures and she occasionally found herself at a loss as to how to deal with them. Zoe had squandered most of the inheritance from her parents on a beachfront cottage, an impractical choice for raising a family. She never exercised, and she was addicted to caffeine. She had uttered the sentence “My husband is dead” to gain sympathy from certain individuals. (The police officer who pulled her over for going ninety miles an hour on Route 3 was one example.)

She had so many flaws.

Zoe liked to think these were, for the most part, hidden, though she understood that among islanders she was considered to be not only a free spirit but a loose cannon. She felt that her parenting was constantly being judged because she was too lax, too lenient. She had been leaving the twins at home by themselves since they were eight years old. When they turned nine, she allowed them to ride their bikes into town. There had been an isolated incident when Hobby rode all the way to Main Street without a helmet. The police chief, Ed Kapenash, had called Zoe at work and told her that by law, he should give her a ticket for allowing her son to ride a bike without a helmet. Zoe replied that she didn’t allow the kids to ride without helmets; since she was at work, she hadn’t been home to see Hobby leave the house without one on. As soon as those words were out of her mouth, she knew how bad they sounded. She thought, Ed Kapenash is going to call Child Protective Services and have the kids taken from me. I am not competent to raise them by myself, after all. Ed Kapenash had sighed and said, “Please tell your children they are never again to ride their bikes without wearing helmets.”

Zoe had left work right that instant. She was all set to punish Hobby, even spank him if necessary, until he told her that his old helmet was too small. Upon investigation, Zoe discovered he was right; there wasn’t a helmet in the house that fit him. He was growing so quickly.

Zoe was sure that the story of Hobby’s not wearing a helmet would spread, and that the citizens of Nantucket would have their suspicions confirmed: she was negligent. Not a helmet in the house that fit the boy! As if that weren’t bad enough, Zoe drove an orange 1969 Karmann Ghia, which she’d bought while she was in culinary school. Although people always honked or waved when Zoe passed, she was sure they were all secretly wondering why she drove two kids around in a car without airbags.

She didn’t buy organic milk.

She was flexible with bedtime and lax about movie ratings.

She allowed the twins to pick their own outfits, which had once resulted in Hobby’s wearing his Little League All-Star jersey five days in a row. It also once led to Penny’s wearing her nightgown to school over a pair of leggings.

But really, how could anyone criticize Zoe’s parenting? She had fabulous, talented kids! The marquis students of the junior class: Hobson and Penelope Alistair.

Let’s start with Hobson, known all his life as Hobby, born five minutes before Penny. He was the reincarnation of his father, also named Hobson Alistair. Hobson senior had been the incredibly tall and commanding man of Zoe’s dreams, a man as big as a tree. Zoe had met him when she was a twenty-one-year-old student at the Culinary Institute of America, in Poughkeepsie. Hobson senior was only six years older than Zoe, but he was already an instructor at the CIA. He taught a class called Meats and was a master butcher; he could take apart a cow or a pig with a cleaver and a boning knife and make it look as elegant as a ballet.

Hobby was big like his father, and graceful and meticulous like his father. Hobby was shaping up to be the best athlete Nantucket Island had seen in forty years. He became the quarterback of the varsity football team as a sophomore; the Whalers had gone 11 and 2 last season and had, most important, beaten Martha’s Vineyard. Hobby also played basketball for the varsity team; he’d been the top scorer since his freshman year. And he played baseball-ace pitcher, home-run king. Watching him, Zoe almost felt embarrassed, as though his prowess were something shameful. He was so much better than anyone else on his own or any opposing team that he commanded everyone’s attention. Zoe always felt like apologizing to the other parents, though Hobby was a good sport. He passed the ball, he cheered for his teammates, and he never claimed more than his share of the glory.

Zoe would overhear the other mothers say things like, “I guess the father was a giant.”

“Are they divorced?”

“No, he died, I think.”

Hobby wanted to be an architect when he grew up. This pleased Zoe. Hobby could be an architect and still live on Nantucket. She was afraid, most of all, of her kids’ leaving the island and never coming back.

“But you can’t force them to stay,” Jordan would tell her. “You know that, right?”

Zoe was certain she would lose Penny. Penny was a gorgeous creature with long, straight black hair and blue eyes and a perfect little nose sprinkled with pale freckles. She had tripped around the house in Zoe’s high heels at age three, had gotten into Zoe’s makeup at age four, and had asked to have her ears pierced at age five. And then, one day when Penny was eight years old, Zoe went to pick up the twins after school, and Mrs. Yurick, the music teacher, was standing out in front with her hand on Penny’s back, waiting for Zoe.

Zoe thought, What? Trouble? Neither of her kids ever misbehaved, so the trouble had to be with Zoe herself. But she wasn’t even late for pickup that day (though she had been late in the past, but never by more than ten minutes-not bad for a working mother). Zoe knew she wasn’t going to win any parenting awards, but she packed healthy lunches for the kids, and when it was cold, she always made sure they each had a hat and gloves. Okay, true, sometimes only one glove.

“Is everything okay?” Zoe asked Mrs. Yurick.

“Your daughter…,” Mrs. Yurick said, and here she put her hand to her bosom, as if she were too overcome with emotion to continue.

What Mrs. Yurick was trying to say was that she had discovered Penelope’s singing voice. A voice as sweet and pure and strong and clear as any Mrs. Yurick had heard.

“You have to do something about this,” Mrs. Yurick said.

Do something? Zoe thought. Like what? But she knew what Mrs. Yurick meant. She, Zoe, the mother of the child with the exceptional singing voice, had to take steps to develop it, to squeeze out every ounce of its potential. Already, Zoe had clocked countless hours at the ball field and the Boys & Girls Club watching Hobby play baseball, football, and basketball. Now she would have to do the same for Penelope’s singing.

And to her credit, Zoe had done it. It hadn’t been easy, or cheap. There had been a voice coach off-island once a week and entire weekends spent with a renowned singing instructor in Boston. Both the voice coach and the singing instructor were wowed by Penny’s talent. She had such range, such maturity. At twelve, she sounded like a woman of twenty-five. She sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” with the Boston Pops the summer following ninth grade. She got the lead in every school musical; she had solos in every madrigal concert.

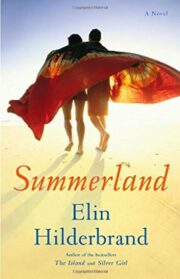

"Summerland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Summerland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Summerland" друзьям в соцсетях.