“No.”

“You’re sure?”

“Yes.”

“You were… where tonight? Where did you start out?”

Jake glared at the Chief. “Why are you interrogating me?” This was brutality, wasn’t it, a barrage of questions like this? This was the Chief abusing his power. Jake’s father had talked about the police overstepping their bounds because it was a small island and they could occasionally get away with it. The Chief and Jordan Randolph had had their differences; there was bad blood over some political thing or another.

The Chief said, “Listen to me, young man, I know you’re hurting. And I’ve been there myself. I lost my best friends, three years ago now, lifelong friends, and now I’m raising their children. I know this is difficult. It may be the most difficult thing you ever do, let’s pray that it is, but I have to try and piece together what happened tonight.” He pressed his lips together until they turned white. “It’s my job to figure out what caused this accident.”

Jake lowered his eyes to his jeans. Penny had written on his jeans in ballpoint pen-a heart containing their initials. She had written on every pair of jeans he owned, and she had written on his T-shirts with Sharpies and on the white rubber of his sneakers, and she had written on his palms. I love you, Jake Randolph. You are mine, I am yours. Forever. It was old-fashioned, better than a text message, she said, more visible: he couldn’t just delete it. If he wanted the markings gone, he would have to scrub. But he didn’t want them gone, and especially not now. It was all he had left: the memory of the pen in Penny’s hand, drawing the heart, tickling his thigh.

“We started at Patrick Loom’s house,” Jake said. The Chief wrote that down, which was silly, because the Chief himself had been at Patrick Loom’s house and had seen Jake there. “Then we went to Steps Beach.”

“Who drove?”

“Me.”

“Why did you drive?”

“It was my Jeep.”

“But you’d been drinking.”

“At Patrick’s?” Jake made what Penny referred to as his “face.” Had the Chief seen him drinking, or was he just assuming? “Yes, sir, I had one beer at Patrick’s. But I was okay to drive.”

The Chief paused. Jake knew he could take issue with the beer he had drunk at the Looms’ house, but that wasn’t important now, was it? Or maybe it was. Jake couldn’t tell.

“Who threw the party at Steps?”

“I have no idea.”

“Please, Jake.”

“I have no clue.”

“Did you know anyone there?”

“I knew everyone there. It was a graduation party. The seniors were there. Probably they all kicked in money and found somebody to buy the keg.”

“Someone like who? David Marcy? Luke Browning?”

“You want to blame them, go ahead,” Jake said. David and Luke were trouble; Luke had an older brother named Larry who was doing time at Walpole for selling cocaine. “They were both there, but neither one of them was bragging about buying the keg. I don’t know who bought the keg.”

The Chief said, “Fair enough.”

Jake said, “I forgot. On the way to Steps we stopped to pick up Demeter Castle.”

“Where did you pick her up?” the Chief asked.

“At the end of her street.”

“At the end of her street? Not at her house?”

“Correct.” Did Jake need to state the obvious here?

“So she was sneaking out, then. Her parents didn’t know she was going out?”

“I didn’t ask her about that,” Jake said.

“And she had alcohol with her?” the Chief asked.

Jake felt relieved. He wasn’t ratting her out if the Chief already knew. “A bottle of Jim Beam.”

“Why did you pick up Demeter? Was it prearranged?”

“No, it was last-minute. She sent Penny a text message.”

“A text message.”

“Saying she had a bottle and she wanted to go out.”

“And for that reason, you went to pick her up. Because she had a bottle.”

“Well,” Jake said, “yeah, sort of.”

“So if she hadn’t texted saying she had a bottle, you wouldn’t have picked her up?”

“She texted saying, ‘Come pick me up,’ and we picked her up.”

“So you’re friends with her?”

“Sort of,” Jake said. “I mean, yes. I’ve known her my entire life. Our parents are friends. You know they’re friends. Why are you making me explain something you already know?”

“Who drank from the bottle?”

“Well, when we picked her up, it was already half gone. So it’s probably safe to say that Demeter had been drinking from the bottle. And then Hobby and I had some.”

“How much?”

“I don’t know,” Jake said. “A couple of swigs?”

“Did Penelope drink from the bottle?”

“No,” Jake said. “Penny didn’t drink. She didn’t like it. It made her sick.” Did he have to tell the Chief about the game of strip poker in tenth grade at Anders Peashway’s house, where they were drinking vodka and grape Kool-Aid and Penny puked into the Peashways’ clawfoot tub? “She had an incident a couple years ago and never drank again.”

“So what happened at Steps Beach?” the Chief asked.

Jake put his head in his hands. What had happened at Steps Beach? He wasn’t sure. He remembered swigging from Demeter’s bottle before they got out of the Jeep, he remembered taking off his shoes, he remembered trudging up over the dunes and seeing the orange blaze of the fire and hearing a Neon Trees song playing on somebody’s iPod, he remembered Penny in the sand next to him, she was drinking Evian water, always Evian water, it was soothing to her vocal cords, she said. She had to stay out of the path of the smoke from the fire, the smoke could harm her vocal cords, one cigarette or toke of marijuana could alter them forever.

At the party Penny had been in a fragile mood. She had been feeling fragile a lot lately, crying over things like graduation and how sad it was that the seniors were graduating and how scary it was that they themselves were now seniors and that this time next year it would be them graduating and leaving everyone behind. Penny was especially worried about leaving her mother. She and Zoe were best friends. After Penny lost her virginity to Jake, she had gone right home and climbed into bed with Zoe and told her everything.

Except lately, there had been things that Penny was telling only Ava.

“Like what?” Jake had asked her.

Penny had ignored this question, which infuriated Jake, though he realized that if there were things that she was telling only to his mother, then she wouldn’t be inclined to turn around and tell him what they were.

Penny had said, “I’ll be sad to leave Ava.”

And then-then!-Jake remembered another thing Penny had said:

“I just want to stay in this moment forever. Like in a bubble, you know? You and me and the fire, staring at the edge of adulthood but never quite reaching it.”

Jake repeated these words to the Chief, and the Chief wrote them down carefully, then cleared his throat. He opened his mouth to speak, and Jake thought, Don’t say it.

“What else do you remember about the party?” the Chief asked.

What else? Kids drinking, smoking cigarettes, smoking weed, pairing off and heading down the beach to make out, kids talking to Jake and Penny, asking them what they were going to do over the summer-Jake was working at the newspaper, Penny had a job hostessing at the Brotherhood, and the last three weeks before school started, she was going to music camp in Interlochen, Michigan. Jake and Penny had repeated these plans to half a dozen people. What Jake didn’t say was that he was planning on taking Penny away to Boston, where they were going to spend the night at the Hotel Marlowe, which would cost a fortune, but Jake had been saving his money for something spectacularly romantic, something that Penny would never forget, and that was what he’d come up with.

“We hung out,” Jake said. “And then we left.”

“Okay,” the Chief said, scooting his chair forward. This was what he’d been waiting for, of course, the details of their leaving. “So whose idea was it to leave?”

Jake couldn’t remember, even though it had been less than two hours earlier. The party was breaking up, and Demeter materialized, her hair hanging in her face and her mouth slack, the way it got when she was smashed. Demeter was a nice girl deep down; she’d been a part of Jake’s life forever and ever, but something had changed in her, she had developed a sharp, shining edge that seemed dangerous. Jake knew enough about girls to know that it had to do with her weight and the fact that she didn’t have close friends and didn’t do as well as she ought to in school. The edge was her defense. She could be mean, sarcastic, snide-even with Penny, and Penny was the only person who was always nice to her. When Demeter had texted earlier that night, above Jake and Hobby’s unspoken protests, Penny had said, “Let’s go pick her up. She’s just sitting home drinking, poor thing.” Demeter had taken up drinking with a vengeance, which Jake found ironic since her parents were teetotalers and pillars of the community.

On the beach Demeter had said, “I have to pee. Come with me, Penny.”

Penny had stood up, wiped the sand off her butt, and dutifully followed Demeter into the dunes. Now Jake wondered if Penny had had to pee as well or if she’d just gone along because Demeter asked her to. What he remembered now was that once the girls had vanished, he had gone looking for Hobby and found him drinking a beer, talking to Patrick Loom. Hobby had a way with people that Jake envied. Hobby was such a phenomenal athlete that people expected him to be as dumb as a bag of hammers, annoyingly self-congratulatory, or at the very least overly interested in the topic of sports. But Hobby socialized like an adult at a cocktail party. He held his drink a certain way, he tilted his head so that you knew he was listening, he asked perceptive questions. He shone so brightly that he made other people shine too. Jake had a lot going for him, everyone told him so, but he was envious of Hobby.

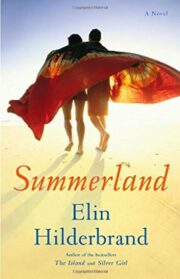

"Summerland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Summerland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Summerland" друзьям в соцсетях.