Rasha and Zoe had stood shoulder to shoulder, beaming at their children, taking pictures with their iPhones. Hobby had brought Claire a bouquet of white roses and calla lilies instead of a corsage.

“They look like they’re getting married,” Zoe had said.

“Don’t they?” Rasha asked. She had smiled wistfully. Because what mother wouldn’t want her daughter to marry Hobby Alistair?

Rasha’s first report from the hospital was that Zoe seemed to be disappearing. She was thin, pale, and trembling. Her dark hair, always so stylishly cut and tipped with reddish highlights, was matted; she didn’t smell that great. She wore gray sweatpants and a gray Nantucket Whalers T-shirt that belonged to Hobby.

Rasha learned that there had been no change in Hobby’s condition.

But at that moment Rasha decided there would be one change, at least: Zoe was going to eat something. Rasha knew that the woman was a chef, that she appreciated good food, and that after a week of sustaining herself on nothing but crackers from the vending machine, she must be hungry. Rasha walked up Cambridge Street to Whole Foods and got one container of chilled summer squash soup and another of Asian chicken salad. She got freshly made hummus and Burrata cheese and bruschetta topping and a whole grain baguette and a pint of fresh raspberries and some bars of dark chocolate. She returned to the hospital with these riches, but by that point both Zoe and Claire were in the room with Hobby. Touching him, talking to him. Rasha herself was able to peek into the room and see Hobby, his left side bandaged like a mummy, his majestic form in repose as if he were a fallen king.

Zoe smoothed the hair off of her son’s face.

Rasha had heard people say less-than-generous things about Zoe Alistair, but at that moment she saw nothing in her but strength and grace.

Day 8: We began to wonder about a funeral for Penny. Her body was at the Lewis Funeral Home on Union Street. Zoe had decided on a burial instead of cremation. But when?

Zoe ate half of the summer squash soup and ten raspberries. This was her first meal since the accident, and it was significant enough news to make the email chain.

Day 9: At ten o’clock at night, phones rang across the island. Annabel Wright, the cheerleading captain, whose family lived out in Sconset, had gotten permission to ring the bells of the Sconset Chapel.

Hobby Alistair had opened his eyes! He had regained consciousness!

ZOE

You would have to be a mother to understand. But how many mothers really could? There were some, Zoe knew this. There were mothers in the world who had sick children, sometimes more than one. There were mothers in the world with sons or daughters in Afghanistan or other war zones, sometimes more than one child. One killed in action, one still fighting.

That was Zoe.

Penny was dead, but Zoe had done some mental yoga and put that information aside for now so that she could focus on Hobby. Ever since the day the twins were born, this had been her modus operandi. Set one down, pick the other one up and nurse her. Give one a bath, put the other one on the soft bathroom rug and let him cry. Help one with her homework, let the other one sit and complain. Watch one play basketball, ask the other to sit in the stands and cheer. Zoe was one woman facing two sets of needs. Splitting her attention had never worked. The kids knew this: either they had her or they didn’t.

For nine days she had given Hobby all of herself. A gatekeeper wielding a long, sharp machete lived in her mind: no other thoughts but of Hobby.

Zoe talked to the doctors. She talked, tersely, to Al Castle: “No change,” she said. “No change.” “Penny will be buried, not cremated.” “No change.” “Tell Jordan not to run a story-nothing, not one word.” “No change.”

Only a mother could be so single-minded. She went back over every second of his life. Everything! Holding him for the first time-just him alone, while the doctors were still pulling out Penny. His eyes squeezed shut, his tiny fist jammed in his mouth. They were twins, but he was technically her firstborn. He had made her a mother. In the first moment of holding him she had felt that magnificent rush of love, powerful and terrifying.

Hobby smiling for the first time, Hobby eating peaches from a jar, roly-poly Hobby, too chubby to pull himself up. His sister was already cruising around the room by holding on to the furniture. He would watch her and start to cry. Zoe had captured it on film. There had been one rare night a few months earlier when both Hobby and Penny were both home for dinner, and Zoe made shrimp and grits, their favorite, and after dinner she pulled out the old videos from when they were babies: Hobby sitting on the floor like a potted plant, bawling his eyes out, and Penny toddling circles around him.

Zoe had tousled Hobby’s hair-sandy like his father’s, not dark like hers and Penny’s-and said, “Oh, but did you catch up to her later!”

Hobby had mastered the art of skipping stones by the time he was four years old. He was always running and jumping, climbing things-trees, cars, bookshelves. Zoe signed him up for swimming lessons at the community pool. Other mothers gossiped or read books while their kids swam, but she rested her chin on the aluminum railing of the balcony and watched Hobby. Zoe could go on forever about the games. His first year playing football at the Boys & Girls Club, the coach had put him in at quarterback. He had quick hands, one of the fathers said, and quick feet. He was a head taller than everyone else on the team. On the basketball court, he shot 75 percent from the free-throw line. He hit his first home run at age ten. Zoe remembered jumping up and down in her chef’s clogs, making a racket against the metal bleachers. Hobby later retrieved the ball out of right field and gave it to her. When Hobby was ten, his mother was his only girl.

There were private things about Hobby, too. For a stretch of months, he’d been afraid of the dark. This was Zoe’s fault. She’d had the Castles and the Randolphs over for dinner one night, and they’d gotten onto the topic of the Columbine shootings. Hobby was still lingering around the dinner table, hoping that one of the adults would pass him an unfinished dessert. And, too, he liked adult conversation more than other kids did. He observed the adult world, then tried to process it so that it made sense to him. Zoe should have banished him from the table that night or put an abrupt end to the discussion, but she had had three or four glasses of Cabernet, and she liked to prove to other people that her kids could thrive in a house where they weren’t constantly sheltered from the harsh realities of the world. And so she had let the conversation go on around him. About the two gunmen-boys hooked on violent video games-who had killed twelve of their classmates and a teacher and then themselves.

That night, Hobby had climbed into bed with her. He was crying. He couldn’t stop thinking about those kids shooting other kids. Killing them.

“I’m sorry,” Zoe had said. Here was her liberal parenting coming back to bite her in the ass. “I shouldn’t have let you hear that.”

He came in night after night for months, for a year.

“What happens when we die?” he asked her once.

Zoe could remember wanting to say something encouraging about Heaven, a place up above where you could sit on a puffy white cloud and watch what was happening on Earth. Where certain angels, maybe, even had the power to make the Red Sox win. But instead, she gave him the only truth she had: “I don’t know. No one knows.”

“Well, where is our father?” he asked.

“Honey,” she said, “I don’t know.”

Hobby pouring milk on his cereal, Hobby lacing up his cleats, Hobby smiling at the girls lined up on the other side of the backstop as he approached the batter’s box and did his own version of genuflecting-touching the end of his bat to each corner of the plate, Father, Son, Holy Spirit.

She should have taken them to church, Zoe thought. She should have given them something to believe in.

She refused to think about Jordan. This was difficult because Jordan had infiltrated all their lives and for two years had been as important to Zoe as oxygen. Jordan had talked to Hobby about colleges. Hobby could go anywhere he liked on a full scholarship, he said. Jordan kept telling Zoe, “You’ve got to stay on top of this. You want him to go to a great school.”

“I want him to be happy,” Zoe said. “He could be happy at UMass.” “One of thousands,” Jordan said.

“Maybe after this island, he’d like that.”

Jordan counseled Hobby about it. Jordan researched various architecture departments-their faculties, their degree requirements. Hobby liked the idea of going to a good college. Stanford, Georgetown, Harvard.

Jordan and Hobby talked about other things as well, including politics and music. Jordan downloaded songs that Hobby suggested-by Eminem, Arcade Fire, Spoon-and Hobby downloaded songs that Jordan suggested, by Neil Young and Joe Cocker, the Who, the Pretenders.

Jordan said to Zoe, “I want to ask him about girls, but I’m afraid.”

“Why girls?” Zoe said.

“I’d like to talk to him about love.”

Zoe could remember thinking, And what, Jordan Randolph, would you tell my son about love? There were times when Jordan’s surrogate fathering bugged the shit out of her.

She said, “I’ll be the one to talk to him about love, thank you very much.”

She’d had a chance to do just that one day when she was driving him home from baseball practice. Penny had gotten her driver’s license, but Hobby had been in the middle of basketball season and had been too busy. He seemed content to let Zoe or Penny chauffeur him around.

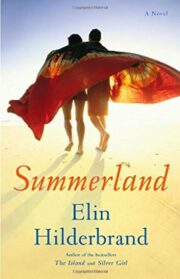

"Summerland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Summerland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Summerland" друзьям в соцсетях.