Early the next morning, I headed down to the hotel’s simple dining room, gobbled down a steaming bun and scalding hot rice soup, then went back to my room. I quickly packed, checked out, hopped into a taxi, then boarded my flight to Jiayu Guan. I thought of visiting the famous pass with its legendary Great Wall fortress and painted bricks from a thousand-year-old tomb, but I couldn’t wait to go to Dunhuang. So as soon as I got off the plane, I took a five-hour train ride to the Land of Grand Prosperity, then a bus to Mogao.

Although Dunhuang was not a required destination, I decided—before undertaking the daunting tasks on the Mountains of Heaven—to treat myself to some aesthetic relief by visiting Mogao’s exquisite Buddhist treasures.

I read that starting from the fourth century, pilgrims, scholars, and especially Buddhist monks passing through this section of the Silk Road decided to stay here to meditate and translate sutras. However, the first cave had not been built until 366 CE by a Buddhist monk who had a vision of thousands of golden dancing lights and a thousand Buddhas. Thus the Mogao Caves are also called Caves of the Thousand Buddhas.

Later, during the religious persecutions in the Tang dynasty, Buddhist monks had come here to hide both themselves and their treasures inside the caves dug by their own hands. They transported hundreds of thousands of treasures across the desert in mule carts and carried them up the cliffs on their own backs.

So long after the cave shrines were built, most of the fifteen-hundred-year-old manuscripts, sculptures, and wall paintings had miraculously remained intact as if the monks’ spirits still traveled through the dim corridors to tell us in the present day of their sufferings and triumphs.

Now, of course, all the monks had long turned into mummies—at least metaphorically—and the Buddhist hideout had become a tourist attraction.

After getting out of the big bus with the other tourists, feeling the hot wind in my face, I headed straight to the Mogao Tourist Office. At the ticket counter, to the surprise and delight of the skinny salesgirl, I asked for a three-hour private tour.

She exclaimed while giving me a once-over, “Welcome to Mogao, the Louvre of the East!”

Maybe she was wondering, how could this ordinary-dressed young woman afford such a luxury, unaware that I’d been savoring the delicious papery texture of the thick pile of renminbi and U.S. dollars in my pants pocket for some time now. Anyway, I figured three hours of private time should be enough to brush shoulders with beauty.

After I told Little Zhang—my young, neatly dressed guide—that I was short on time, she smiled politely. “Miss, then I’ll first take you to see something very special in cave number 108.”

She led me on a short walk before we turned a corner where the cliff face of Mogao revealed its full-fledged majesty in front of my eyes. I held my breath at the stunning site—beehivelike cave temples surrounded by the vast expanse of sand, above which sat a boundless patch of sky in royal blue. More than a thousand years ago the monks, with nothing but their bare hands and a few primitive tools, had carved out the whole mountain to build these temples in the midst of golden infinity.

“Amazing, isn’t it? The whole temple built at the precipice of Mingsha Mountain.” The Mount of Singing Sand.

Before I could respond, she pointed upward to a cave. “You think you can make it up there?”

“I’ll try.”

“Don’t worry, it looks steep, but the climb is actually not that hard.”

After about fifteen minutes, during which the relentless sun, fierce concentration, and unsettling silence took over, we finally arrived at the entrance to the cave. She led me inside an officelike area where a young man was arranging paper, pens, pencils, plastic trays, small boxes, and other paraphernalia on a wooden desk.

“Hi. How come only one guest?” the young fellow asked, giving me a suspicious once-over. “A bad day?”

Zhang hit his shoulder with her small fist, giggling. “You know very well that’s a good day. Less work and more money.”

“All right, now go do your job, we’ll talk later.”

Zhang sent him a flirtatious glance, then handed me a small flashlight and motioned me to follow her into the dim interior. “Every cave here has this narrow entrance leading to the main chamber. This is to protect the cave and its art from the sunlight.”

Walking in front of me, she directed her light to shine on depictions of flying goddesses playing musical instruments, while continuing to explain in her tourist guide’s singsong voice, “Although this cave is more than one thousand years old, it is very well preserved. See, all the colors—malachite green, ochre, lapis lazuli—all still vibrant with only minimum damage.”

Seeing the turquoise of one goddess’s robe unbelievably luminous, my finger, as if suddenly possessed by an independent will, reached to touch.

Quickly Zhang grabbed my wrist. Her move was so sudden and her grip so sharp and strong that I let out a loud “Aiiiiya!”

“Sorry,” she said, without looking as if she were, “you cannot touch. Any slight human contact will cause severe damage. Miss, if everyone is curious like you, these frescoes will be gone in no time!”

“I’m sorry,” I said, not meaning it either. Bitterness and depression always engulfed me when I could not touch what was beautiful.

But soon after we stepped inside the main room, both my bitterness and depression fizzled out like bubble water.

A huge, towering Guan Yin, the Goddess of Compassion, looked down at me with lowered eyes. Gigantic yet refined, her face exuded compassion. I followed her hands up to a small Buddha sitting on the front of her bejeweled crown. Orange-pink, maroon, and turquoise ribbons flew out from behind her brown robe, frolicking in intricately choreographed dances. The goddess looked so powerful and her energy so strong that all my own negative energy was extinguished—even my annoyance at Zhang.

Just when I was in the process of being purified by this stunning image, Zhang’s voice rose next to my ears. “This is a Tantric Guan Yin done eight hundred years ago. Named Thousand-Arms Guan Yin, she could reach out to help the many needy beings in the sea of suffering. She…”

I cut off her rote recitation. “Little Zhang, do you mind leaving me alone with Guan Yin for a few minutes?”

She cast a curious glance at me, as if asking why would I want to be alone when I’d paid extra for the private tour? “All right, but make sure you don’t touch anything and give me your camera. I’ll be waiting at the office.” She had barely finished when her scrawny hand reached out to snatch away my camera. Then her small feet swiftly carried her petite frame outside the cave.

With Guan Yin all to myself, I quietly admired her serene face, her flowing robe, and the glowing halo behind her back. My desire to take pictures had vanished like the morning dew. Now I did not want to disturb the goddess’s peace or remember her beauty through mere sheets of glossy paper. I stared at her, trying to burn her image into my mind, so it would never get lost but would stay with me till the end of my days.

More meditative moments passed, then a realization struck me. The circle framing the goddess’s back was not a huge halo but a disc painted with hundreds of compact arms.

The image was so powerful that I fell back a step. Or was I being pushed by the goddess’s overwhelming qi?

Captivated by this thousand-year-old, thousand-armed woman, I slowly moved my eyes to meet hers. Besides the pair on her face, there was another on her forehead and one on each of her thousand extended palms. I felt my body floating in a trance, enjoying the delicious sensation of riding waves of her powerful yet gentle vibrations. Then something strange happened.

Guan Yin was crying.

Tears flooded from her eyes, not only those on her face but all her other eyes in unison.

My heart knocked against my ribs.

To my disbelief, something more happened.

The goddess’s innumerable eyes were moving around as if to scrutinize the room. Her thousand arms made circular movements like an octopus’s tentacles, choreographing some mystical dance in the surreal space….

I pinched my own cheeks, then rubbed my eyes. “No, this can’t be real. I’m just hallucinating!”

In fact, I didn’t want to know the truth. I wanted to keep this experience in a secret chamber of my heart, safely locked away forever. Does the truth always matter?

As I hurried toward the exit, I felt the goddess’s many blinking hands reaching out toward my sweating back….

I ran to the office, snatched my camera back from Zhang, dashed down the stairs to level ground, and climbed onto the first available bus back to Dunhuang.

5

Xinjiang—New Frontier

That night I stayed at a hotel in Dunhuang. As I lay awake in bed, through my mind floated the image of Guan Yin with her thousand weeping eyes and waltzing arms. Had the goddess tried to tell me something? To be more compassionate—since we sentient beings are all suffering in one way or another on this polluted planet? That I should have been nicer to Alex Luce?

Apparently, my ability to “see” was still very much alive after all these years.

As a child, my acute sensitivity to vibrations from other dimensions made me “the little girl who sees things.” Most adults dismissed my “seeing” as a lonely child’s overactive imagination, but a few, mostly older Chinese, asked me to “lend my eyes” to explain mysteries, communicate with the dead, and visit an apartment before its purchase to see if it was still infested with “unclean” presences.

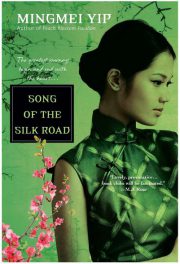

"Song of the Silk Road" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Song of the Silk Road". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Song of the Silk Road" друзьям в соцсетях.