Keku gave me two discarded calendars from previous years. I cut off the grids and pasted the pictures on the wall. One was the Heavenly Maiden Scattering Flowers. Her sweet face and the waltzing flowers against a cloud-laden, azure sky immediately lifted my mood. The other was a Chinese garden with a pavilion and a vermillion bridge arched over a pond laced with goldfish. Keku also gave me her red headscarf, three crates, and a part-time functional boom box with five Xinjiang folk music tapes. From one of the occasional passing three-wheeled carts, I bought an assortment of candles and a small carpet. Now at night, three reddish-orange candles stood on my wooden crates, scattering yellowish light in my little home like mini desert-setting suns.

A week later, I looked around my tiny refuge and felt a surge of happiness—like the rising desert sun.

My neighbors were mostly Uyghur people who lived a very meager life with few possessions. It surprised me how quickly I was able to make friends in this small piece of exotic land. Most of the men either farmed or worked in the next village as vendors selling clothes, fabrics, plastic utensils, dried fruits, grilled lamb. The wives, besides taking care of their small children, helped raise cows and sheep and sewed hats and clothing at night to take in extra income.

At first, the village women would bring their little ones to play in front of my cottage, peer inside my house to watch my every move, then giggle and run away when I spotted them. Everyone knew about the “stranger in town.” Some cast me friendly glances, while others, especially older people, watched my every move as if I were a shadow that had just lost its body. I tried my best to keep a smile on my face wherever I went.

To please the friendly yet overcurious villagers, I decided I would give the women cheap jewelry and spices and the old people medicine oil I bought in the next village. For the children, I’d bribe them with candies and small toys so they’d run simple errands for me—taking pictures, delivering messages, and finding oddities for me like strangely shaped stones, twigs, or fossils.

Once I had finished fixing up my cottage and had time on my hands, I began to stroll around taking pictures. Local women and children adorned with colorful scarves and exotic costumes were my favorites. My other subjects included poplar and fig trees, the sheep and cows raised by the villagers, passing three-wheeled carts loaded with trinkets, and the little store that sold plastic utensils, sugar, flour, spices, dried fruits, canned food. When I tired of this I would go back to my cottage and write in my journal or reread the books I had brought with me.

As much as I was happy with the cheerful decoration of my new home, I also felt uncomfortable living there, especially at night. When the temperature dropped, even with my blankets, I felt chilled and sometimes my teeth would chatter. Anything moving outside my window would make me think of visitors from another dimension. Then I found myself thinking of Alex. It would be really nice to have him around. Men are useful after all. There are so many things they can do, both inside and outside a house, in a city or out in the desert—let alone having a warm body as company.

In fact, what really bothered me at night was not the cold, but something else. I felt suffocated. But by what? It took me a few days to realize it was the qi. It’s not that its circulation was blocked, but that it was oppressive. Strangely, though the cottage was tiny and its qi constricted, I also felt engulfed by an immense, chilly emptiness. Some nights I had nightmares of floods and woke up gasping for air. Were the tears from Guan Yin flooding all the way from Mogao to this village? Who was she crying for?

I seemed to find the answer one day when I took a long walk half a mile away from my cottage.

A graveyard.

There were just five graves, all marked with a thin wooden board inscribed with faded red paint. As I was trying to decipher the characters on the first grave marker, I suddenly heard footsteps in the distance. Swiftly I moved behind a boulder to watch.

It was a fortyish, muscular, tan-faced man.

He walked straight to one of the graves, dropped to his knees, and fervently prayed. Then he did the same at all the other graves, his face sad beyond words. My heart would often melt when I saw a sad face; for me it was a window to tragedy, mystery, and poetry—qualities that fascinated me. But this one looked so sad that there was no room left for any of these.

Finally when the man finished his prayer, he stood up, pressed his lips against each grave marker, and started to leave. I lowered myself so he wouldn’t see me. With his eyes unfocused and his expression hollow, I doubted if he was alert to anything around him, except perhaps those six feet under.

After making sure that the stranger was gone, I went up to take a good look at the two graves to which he’d paid the most respect. I took out my pen and paper, trying to copy the inscriptions, but one of them was so damaged that I ended up copying only one.

Back home, I asked Keku to translate the inscription for me.

1981–1986 Tangri, beloved son of the Limbit family. His five years of life on this planet gave joy and peace to many people, especially his loving parents and doting grandparent. May his beautiful body and soul rest in heaven.

I couldn’t even imagine the overwhelming sorrow to have lost a child at this tender age. What had happened?

Later, I asked Keku more about the burial sites, but she only widened her eyes. “Nobody knows. Nobody goes.”

Then I told her about the sad-faced stranger. “Do you think it was his son buried there?”

“Don’t know. Never ask. Bad luck. Better not go there yourself.”

“You’re not curious about this man and his dead relatives, friends?”

She didn’t answer my question, but sighed. “Miss Lin, now understand why rent cheap?” She paused, then, “Why no people, no thieves come here steal?”

I felt a shudder inside. Who were this village’s real residents, the Muslims or the phantoms?

But I thought it might actually turn out to be something good. Maybe I could know this area better by communicating with spirits—ancestors who might tell me tales about the mountains and the desert that the living didn’t know or wouldn’t tell. Of course, I would not tell anyone about this ability of mine, for I had no intention of being stigmatized by my new acquaintances as crazy or, worse, a witch.

Since my teens, I’d been attracted to graveyards—perfect places for me to read without the slightest disturbance, since the dead stay out of your way and don’t try to engage you in boring conversations. I’d never had more than one or two friends for I never had much in common with my classmates.

Besides the ordinary dead people, there were other kinds of spirits I connected with, especially deceased authors. So from time to time, I’d skip class and take the bus to the graveyard in Happy Valley where I would read Sense and Sensibility, Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Alice in Wonderland, The Sun Also Rises…

When I tired of reading my books, I’d walk around to read inscriptions on gravestones. I found it fascinating when a person died either very young or very old, since I was alive but stuck in between. I also tried to talk to the deceased, easing my teenage angst and filling my mind with otherworldly romances. The graveyard was an escape from the boredom of school and life into a world of fantasy and magical possibilities.

After I found the graveyard, my nocturnal feeling of suffocation stopped but the cold, empty feeling lingered.

A few days later, I was eating my simple breakfast of bread and milk and listening to cheerful, exotic Xinjiang tunes when I heard stirring outside the door. I went to lift the curtain, peered outside the window, and was astonished to see Alex Luce fidgeting in front of the entrance.

Like a hungry ghost, this kid just wouldn’t leave me alone!

I flung open the door and screamed in his face, “Alex, what are you doing here? You following me again?”

But his young face, agonized and exhausted, instantly melted my heart.

“Don’t be mad, Lily. I just wanted to be sure you’re OK.”

“I’m fine.” Seeing that he was sweating heavily under the hot sun, my heart melted again. “You want to come in?”

He nodded.

Inside, I signaled for him to sit on one of the floral “sofas.” After that, I poured water for him in a tin cup, then sat opposite him.

“I just moved here.”

“What do you mean by moved here?”

He pointed to the far distance outside the window. “I’ll camp over there.”

“At the graveyard?” I couldn’t believe my ears. “Why, are you out of your mind?”

“So I can look out for you, Lily, in case anything happens.”

“So you followed me here?”

“I paid the guy at the hotel to tell me where you are. I hope you aren’t offended.” He lowered his head. His voice came out tender like water, just what I needed in the desert.

Then he gulped down his water, put down the cup with a gentle clink, and looked me in the eyes. “Lily, I’m in love with you.”

I tried to sound calm despite my desert-hot emotions. “But, Alex, we hardly know each other.”

“Does it really matter? Either you love or you don’t, there’s no but in a relationship.”

“Then what do you want?” I asked, feeling hot, uneasy, impatient.

“Let me love you by taking care of you.”

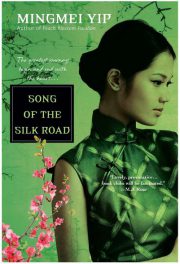

"Song of the Silk Road" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Song of the Silk Road". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Song of the Silk Road" друзьям в соцсетях.