What is it this time? I think, as I hit play.

"Hi, Rachel… It's me… Dex… I wanted to call you yesterday to talk about Saturday night but-I just couldn't. I think we should talk about it, don't you? Call me when you can. I should be around all day."

My heart sinks. Why can't he adopt some good old-fashioned avoidance techniques and ignore it, never speak of it again? That was my game plan. No wonder I hate my job; I am a litigator who hates confrontation. I pick up a pen and tap it against the edge of my desk. I hear my mother telling me not to fidget. I put the pen down and stare at the blinking light. The woman demands that a decision be made with respect to this message-I must replay it, save it, or delete it.

What does he want to talk about? What is there to say? I replay, expecting the answers to come to me in the sound of his voice, his cadence. But he gives nothing away. I replay again and again until his voice starts to sound distorted, just as a word changes in your mouth when you repeat it enough times. Egg, egg, egg, egg. That used to be my favorite. I'd say it over and over until it seemed that I had the altogether wrong word for the yellow substance I was about to eat for breakfast.

I listen to Dex one final time before I delete him. His voice definitely sounds different. This makes sense because in some ways, he is different. We both are. Because even if I try to block out what happened, even if Dex drops the Incident after a brief, awkward telephone call, we will forever be on one another's List-that list every person has, whether recorded in a secret spiral notebook or memorized in the back of the mind. Whether short or long. Whether ranked in order of performance or importance or chronology. Whether complete with first, middle, and last names or mere physical descriptions, like Darcy's List: "Delta Sig with killer delts…"

Dex is on my List for good. Without wanting to, I suddenly think of us in bed together. For those brief moments, he was just Dex-separate from Darcy. Something he hadn't been in a very long time. Something he hadn't been since the day I introduced the two.

I met Dex during our first year of law school at NYU. Unlike most law students, who come straight from college when they can think of nothing better to do with their stellar undergrad transcripts, Dex Thaler was older, with real-life experience. He had worked as an analyst at Goldman Sachs, which blew away my nine-to-five summer internships and office jobs filing and answering phones. He was confident, relaxed, and so gorgeous that it was hard not to stare at him. I was positive that he would become the Doug Jackson and Blaine Conner of law school. Sure enough, we were barely into our first week of class when the buzz over Dexter began, women speculating about his status, noting either that his left ring finger was unadorned or, alternatively, worrying that he was too well dressed and handsome to be straight.

But I dismissed Dex straightaway, convincing myself that his outward perfection was boring. Which was a fortunate stance, because I also knew that he was out of my league. (I hate that expression and the presumption that people choose mates based so heavily upon looks, but it is hard to deny the principle when you look around-partners generally share the same level of attractiveness, and when they do not, it is noteworthy.) Besides, I wasn't borrowing thirty thousand dollars a year so that I could find a boyfriend.

As a matter of fact, I probably would have gone three years without talking to him, but we randomly ended up next to each other in Torts, a seating-chart class taught by the sardonic Professor Zigman. Although many professors at NYU used the Socratic method, only Zigman used it as a tool to humiliate and torture students. Dex and I bonded in our hatred of our mean-spirited professor. I feared Zigman to an irrational extreme, whereas Dexter's reaction had more to do with disgust. "What an asshole," he would growl after class, often after Zigman had reduced a fellow classmate to tears. "I just want to wipe that smirk off his pompous face."

Gradually, our grumbling turned into longer talks over coffee in the student lounge or during walks around Washington Square Park. We began to study together in the hour before class, preparing for the inevitable-the day Zigman would call on us. I dreaded my turn, knowing that it would be a bloody massacre, but secretly couldn't wait for Dexter to be called on. Zigman preyed on the weak and flustered, and Dex was neither. I was sure that he wouldn't go down without a fight.

I remember it well. Zigman stood behind his podium, examining his seating chart, a schematic with our faces cut from the first-year look book, practically salivating as he picked his prey. He peered over his small, round glasses (the kind that should be called spectacles) in our general direction, and said, "Mr. Thaler."

He pronounced Dex's name wrong, making it rhyme with "taller."

"It's 'Thaa-ler,' " Dex said, unflinching.

I inhaled sharply; nobody corrected Zigman. Dex was really going to get it now.

"Well, pardon me, Mr. Thaaa-ler," Zigman said, with an insincere little bow. "Palsgraf versus Long Island Railroad Company."

Dex sat calmly with his book closed while the rest of the class nervously flipped to the case we had been assigned to read the night before.

The case involved a railroad accident. While rushing to board a train, a railroad employee knocked a package of dynamite out of a passenger's hand, causing injury to another passenger, Mrs. Palsgraf. Justice Car-dozo, writing for the majority, held that Mrs. Palsgraf was not a "foreseeable plaintiff" and, as such, could not recover from the railroad company. Perhaps the railroad employees should have foreseen harm to the package holder, the Court explained, but not harm to Mrs. Palsgraf.

"Should the plaintiff have been allowed recovery?" Zigman asked Dex.

Dex said nothing. For a brief second I panicked that he had frozen, like others before him. Say no, I thought, sending him fierce brain waves. Go with the majority holding. But when I looked at his expression, and the way his arms were folded across his chest, I could tell that he was only taking his time, in marked contrast to the way most first-year students blurted out quick, nervous, untenable answers as if reaction time could compensate for understanding.

"In my opinion?" Dex asked.

"I am addressing you, Mr. Thaler. So, yes, I am asking for your opinion."

"I would have to say yes, the plaintiff should have been allowed recovery. I agree with Justice Andrew's dissent."

"Ohhhh, really?" Zigman's voice was high and nasal.

"Yes. Really."

I was surprised by his answer, as he had told me just before class that he didn't realize crack cocaine had been around in 1928, but Justice Andrews surely must have been smoking it when he wrote his dissent. I was even more surprised by Dexter's brazen "really" tagged onto the end of his answer, as though to taunt Zigman.

Zigman's scrawny chest swelled visibly. "So you think that the guard should have foreseen that the innocuous package measuring fifteen inches in length, covered with a newspaper, contained explosives and would cause injury to the plaintiff?"

"It was certainly a possibility."

"Should he have foreseen that the package could cause injury to anybody in the world?" Zigman asked, with mounting sarcasm.

"I didn't say 'anybody in the world.' I said 'the plaintiff.' Mrs. Pals-graf, in my opinion, was in the danger zone."

Zigman approached our row with ramrod posture and tossed his Wall Street Journal onto Dex's closed textbook.

"Care to return my newspaper?"

"I'd prefer not to," Dex said.

The shock in the room was palpable. The rest of us would have simply played along and returned the paper, mere props in Zigman's questioning.

"You'd prefer not to?" Zigman cocked his head.

"That's correct. There could be dynamite wrapped inside it."

Half of the class gasped, the other half snickered. Clearly, Zigman had some tactic up his sleeve, some way of turning the facts around on Dex. But Dex wasn't falling for it. Zigman was visibly frustrated.

"Well, let's suppose you did choose to return it to me and it did contain a stick of dynamite and it did cause injury to your person. Then what, Mr. Thaler?"

"Then I would sue you, and likely I would win."

"And would that recovery be consistent with Judge Cardozo's rationale in the majority holding?"

"No. It would not."

"Oh, really? And why not?"

"Because I'd sue you for an intentional tort, and Cardozo was talking about negligence, was he not?" Dex raised his voice to match Zigman's.

I think I stopped breathing as Zigman pressed his palms together and brought them neatly against his chest as though he were praying. "I ask the questions in this classroom. If that's all right with you, Mr. Thaler?"

Dex shrugged as if to say, have it your way, makes no difference to me.

"Well, let's suppose that I accidentally dropped my paper onto your desk, and you returned it and were injured. Would Mr. Cardozo allow you full recovery?"

"Sure."

"And why is that?"

Dex sighed to show that the exercise was boring him and then said swiftly and clearly, "Because it was entirely foreseeable that the dynamite could cause injury to me. Your dropping the paper containing dynamite into my personal space violated my legally protected interest. Your negligent act caused a hazard apparent to the eye of ordinary vigilance."

I studied the highlighted portions of my book. Dex was quoting sections of Cardozo's opinion verbatim, without so much as glancing at his book or notes. The whole class was spellbound-nobody did this well, and certainly not with Zigman looming over him.

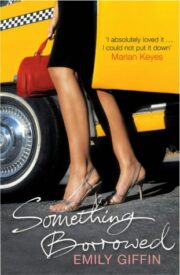

"Something borrowed" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Something borrowed". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Something borrowed" друзьям в соцсетях.