Except that I’ve been to the college gym, and it’s scary. There are all these really skinny girls there, flinging their stick-like arms around in aerobics classes and yoga and stuff. Seriously, one of these days, one of them is going to put someone’s eye out.

Anyway, if I lose enough weight, Rachel says, I’ll definitely get a hot boyfriend, the way she’s planning to, just as soon as she finds a guy in the Village who isn’t gay, has a full set of hair, and makes at least a hundred thousand a year.

But how on earth could anyone ever give up cold sesame noodles? Even for a guy who makes a hundred thousand dollars a year?

Plus, um, as I frequently remind Rachel, size 12 is not fat. It is the size of the average American woman. Hello. And there are plenty of us (size 12s) who have boyfriends, thank you very much.

Not me, necessarily. But plenty of other girls my size, and even larger.

But though Rachel and I have different priorities—she wants a boyfriend; I’d just take a BA, at this point—and can’t seem to agree on what constitutes a meal—her, lettuce, no dressing; me, falafel, extra tahini, with a pita ’n’ hummus starter and maybe an ice cream sandwich for dessert—we get along okay, I guess. I mean, Rachel seems to understand the look I shoot her about Mrs. Allington, anyway.

“Mrs. Allington,” she says. “Let’s get you home, shall we? I’ll take you upstairs. Would that be all right, Mrs. Allington?”

Mrs. Allington nods weakly, her interest in my career change forgotten. Rachel takes the president’s wife by the arm as Pete, who has been hovering nearby, holds back a wave of firemen to make room for her and Mrs. A. on the elevator they’ve turned back on especially for her. I can’t help glancing nervously at the elevator’s interior as the doors open. What if there’s blood? I know they said they’d found her at the bottom of the shaft, but what if part of her was still on the elevator?

But there’s no blood that I can see. The elevator looks the same as ever, imitation mahogany paneling with brass trim, into which hundreds of undergraduates have scratched their initials or various swear words with the edges of their room keys.

As the elevator doors close, I hear Mrs. Allington say, very softly, “The birds.”

“God,” Magda says, as we watch the numbers above the elevator doors light up as the car moves toward the penthouse. “I hope she doesn’t throw up again in there.”

“Seriously,” I agree. That would make the ride up twenty flights pretty much suck.

Magda shakes herself, as though she’s thought of some thing unpleasant—most likely Mrs. A.’s vomit—and looks around. “It’s so quiet,” she says, hugging herself. “It hasn’t been this quiet around here since before all my little movie stars checked in.”

She’s right. For a building that houses so many young people—seven hundred, most still in their teens—the lobby is strangely still just then. No one is grumbling about the length of time it takes the student workers to sort the mail (approximately seven hours. I’d heard that Justine could get them to do it in under two. Sometimes I wonder if maybe Justine had some sort of secret pact with Satan); no one is complaining about the broken change machines down in the game room; no one is Rollerblading on the marble floors; no one is arguing with Pete over the guest sign-in policy.

Not that there isn’t anybody around. The lobby is jumping. Cops, firemen, college officials, campus security guards in their baby blue uniforms, and a smattering of students—all resident assistants—are milling around the mahogany and marble lobby, grim-faced…

… but silent. Absolutely silent.

“Pete,” I say, going up to the guard at the security desk. “Do you know who it was?”

The security guards know everything that goes on in the buildings they work in. They can’t help it. It’s all there, on the monitors in front of them, from the students who smoke in the stairwells, to the deans who pick their noses in the elevators, to the librarians who have sex in the study carrels…

Dishy stuff.

“Of course.” Pete, as usual, is keeping one eye on the lobby and the other on the many television monitors on his desk, each showing a different part of the dorm (I mean, residence hall), from the entranceway to the Allingtons’ penthouse apartment, to the laundry room in the basement.

“Well?” Magda looks anxious. “Who was it?”

Pete, with a cautious glance at the reception desk across the way to make sure the student workers aren’t eavesdropping, says, “Kellogg. Elizabeth. Freshman.”

I feel a spurt of relief. I have never heard of her.

Then I berate myself for feeling that way. She’s still a dead eighteen-year-old, whether she was one of my student workers, or not!

“How did it happen?” I ask.

Pete gives me a sarcastic look. “How do you think?”

“But,” I say. I can’t help it. Something is really confusing me. “Girls don’t do that. Elevator surf, I mean.”

“This one did.” Pete shrugs.

“Why would she do something like that?” Magda wants to know. “Something so stupid? Was she on drugs?”

“How should I know?” Pete seems annoyed by our barrage of questions, but I know it is only because he is as freaked as we are. Which is weird, because you’d think he’s seen it all: He’s been working at the college for twenty years. Like me, he’d taken the job for the benefits: A widower, he has four children who are assured of a great—and free—college education, which is the main reason he’d gone to work for an academic institution after a knee injury got him assigned to permanent desk duty in the NYPD. His oldest, Nancy, wants to be a pediatrician.

But that doesn’t keep Pete’s face from turning beet red every time one of the students, bitter over not being allowed into the building with their state-of-the-art halogen lamps (fire hazard), refers to him as a “rent-a-cop.” Which isn’t fair, because Pete is really, really good at his job. The only time pizza delivery guys ever make it inside Fischer Hall to stick menus under everyone’s door is when Pete’s not on duty.

Not that he doesn’t have the biggest heart in the world. When kids come down from their rooms, disgustedly holding glue traps on which live mice are trapped, Pete has been known to take the traps out to the park and pour oil onto them to free their little paws and let them go. He can’t stand the idea of anyone—or anything—dying on his watch.

“Coroner’ll run tests for alcohol and drugs, I’m sure,” he says, trying to sound casual, and failing. “If he ever gets here, that is.”

I’m horrified.

“You mean she… she’s still here? I mean, it—the body?”

Pete nods. “Downstairs. Bottom of the elevator shaft. That’s where they found her.”

“That’s where who found her?” I ask.

“The fire department,” Pete says. “When someone reported seeing her.”

“Seeing her fall?”

“No. Seeing her lying there. Someone looked down the crack—you know, between the floor and the elevator car—and saw her.”

I feel shaken. “You mean nobody reported it when it happened? The people who were with her?”

“What people?” Pete wants to know.

“The people she was elevator surfing with,” I say. “She had to be with someone. Nobody plays that stupid game alone. They didn’t come down to report it?”

“Nobody said nothing to me,” Pete says, “until this morning when a kid saw her through the crack.”

I am appalled.

“You mean she could have been lying down there for hours?” I ask, my voice cracking a little.

“Not alive,” Pete says, getting my drift right away. “She landed headfirst.”

“Santa Maria,” Magda says, and crosses herself.

I am only slightly less appalled. “So… then how’d they know who it was?”

“Had her school ID in her pocket,” Pete explains.

“Well, at least she was thinking ahead,” Magda says.

“Magda!” I’m shocked, but Magda just shrugs.

“It’s true. If you are going to play such a stupid game, at least keep ID on you, so they can identify your body later, right?”

Before either Pete or I can reply, Gerald, the dining director, comes popping out of the cafeteria, looking for his wayward cashier.

“Magda,” he says, when he finally spots her. “Whadduyadoing? Cops said they’re gonna let us open up again any minute and I got no one on the register.”

“Oh, I’ll be right there, honey,” Magda calls to him. Then, as soon as he’s stomped out of earshot, she adds, “Dickhead.” Then, with an apologetic waggle of her nails at Pete and me, Magda goes back to her seat behind the cash register in the student cafeteria around the corner from the guard’s desk.

“Heather?”

I look around, and see one of the student workers at the reception desk gesturing to me desperately. The reception desk is the hub of the building, where the residents’ mail is sorted, where visitors can call up to their friends’ rooms, and where all building emergencies are supposed to be reported. One of my first duties after being hired had been to type up a long list of phone numbers that the reception desk employees were to refer to in the event of an emergency of any kind (apparently, Justine had been too busy using college funds to buy ceramic heaters for all of her friends ever to get around to this).

Fire? The number for the fire station was listed.

Rape? The number for the campus’s rape hotline was listed.

Theft? The number for the Sixth Precinct.

People falling off the top of one of the elevators? There’s no number for that.

“Heather.” The student worker, Tina, sounds as whiny today as she did the first day I met her, when I told her she couldn’t put people on hold while she finished the round of Tetris she was playing on her Game Boy (Justine had never had a problem with this, I was told). “When’re they gonna get rid of that girl’s body? I’m losing it, knowing she’s, like, still DOWN there.”

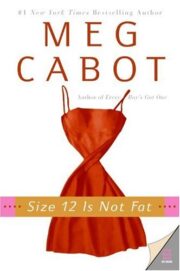

"Size 12 Is Not Fat" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Size 12 Is Not Fat". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Size 12 Is Not Fat" друзьям в соцсетях.