Three guys got out of the truck and headed for the back of it, two of them starting to lift down the equipment. They looked older, like maybe they were in college, and I stayed frozen on the steps, watching them. I knew that this was an opportunity to try and get some information, but that would involve talking to these guys. I’d been shy from birth, but the last two years had been different. With Sloane by my side, it was like I suddenly had a safety net. She was always able to take the lead if I wanted her to, and if I didn’t, I knew she would be there, jumping in if I lost my nerve or got flustered. And when I was on my own, awkward or failed interactions just didn’t seem to matter as much, since I knew I’d be able to spin it into a story, and we could laugh about it afterward. Without her here, though, it was becoming clear to me how terrible I now was at navigating things like this on my own.

“Hey.” I jumped, realizing I was being addressed by one of the landscapers. He was looking up at me, shielding his eyes against the sun as the other two hefted down a riding mower. “You live here?”

The other two guys set the mower down, and I realized I knew one of them; he’d been in my English class last year, making this suddenly even worse. “No,” I said, and heard how scratchy my voice sounded. I had been saying only the most perfunctory things to my parents and younger brother over the last two weeks, and the only talking I’d really been doing had been into Sloane’s voice mail. I cleared my throat and tried again. “I don’t.”

The guy who’d spoken to me raised his eyebrows, and I knew this was my cue to go. I was, at least in their minds, trespassing, and would probably get in the way of their work. All three guys were now staring at me, clearly just waiting for me to leave. But if I left Sloane’s house—if I ceded it to these strangers in yellow T-shirts—where was I going to get more information? Did that mean I was just accepting the fact that she was gone?

The guy who’d spoken to me folded his arms across his chest, looking impatient, and I knew I couldn’t keep sitting there. If Sloane had been with me, I would have been able to ask them. If she were here, she probably would have gotten two of their numbers already and would be angling for a turn on the riding mower, asking if she could mow her name into the grass. But if Sloane were here, none of this would be happening in the first place. My cheeks burned as I pushed myself to my feet and walked quickly down the stone steps, my flip-flops sliding once on the leaves, but I steadied myself before I wiped out and made this more humiliating than it already was. I nodded at the guys, then looked down at the driveway as I walked over to my car.

Now that I was leaving, they all moved into action, distributing equipment and arguing about who was doing what. I gripped my door handle, but didn’t open it yet. Was I really just going to go? Without even trying?

“So,” I said, but not loudly enough, as the guys continued to talk to each other, none of them looking over at me, two of them having an argument about whose turn it was to fertilize, while the guy from last year’s English class held his baseball cap in his hands, bending the bill into a curve. “So,” I said, but much too loudly this time, and the guys stopped talking and looked over at me again. I could feel my palms sweating, but I knew I had to keep going, that I wouldn’t be able forgive myself if I just turned around and left. “I was just . . . um . . .” I let out a shaky breath. “My friend lives here, and I was trying to find her. Do you—” I suddenly saw, like I was observing the scene on TV, how ridiculous this probably was, asking the landscaping guys for information on my best friend’s whereabouts. “I mean, did they hire you for this job? Her parents, I mean? Milly or Anderson Williams?” Even though I was trying not to, I could feel myself grabbing on to this possibility, turning it into something I could understand. If the Williamses had hired Stanwich Landscaping, maybe they were just on a trip somewhere, getting the yard stuff taken care of while they were gone so they wouldn’t be bothered. It was just a long trip, and they had gone somewhere with no cell reception or e-mail service. That was all.

The guys looked at each other, and it didn’t seem like any of these names had rung a bell. “Sorry,” said the guy who’d first spoken to me. “We just get the address. We don’t know about that stuff.”

I nodded, feeling like I’d just depleted my last reserve of hope. Thinking about it, the fact that landscapers were here was actually a bit ominous, as I had never once seen Anderson show the slightest interest in the lawn, despite the fact that the Stanwich Historical Society was apparently always bothering him to hire someone to keep up the property.

Two of the guys had headed off around the side of the house, and the guy from my English class looked at me as he put on his baseball cap. “Hey, you’re friends with Sloane Williams, right?”

“Yes,” I said immediately. This was my identity at school, but I’d never minded it—and now, I’d never been so happy to be recognized that way. Maybe he knew something, or had heard something. “Sloane’s actually who I’m looking for. This is her house, so . . .”

The guy nodded, then gave me an apologetic shrug. “Sorry I don’t know anything,” he said. “Hope you find her.” He didn’t ask me what my name was, and I didn’t volunteer it. What would be the point?

“Thanks,” I managed to say, but a moment too late, as he’d already joined the other two. I looked at the house once more, the house that somehow no longer even felt like Sloane’s, and realized that there was nothing left to do except leave.

I didn’t head right home; instead I stopped in to Stanwich Coffee, on the very off chance that there would be a girl in the corner chair, her hair in a messy bun held up with a pencil, reading a British novel that used dashes instead of quotation marks. But Sloane wasn’t there. And as I headed back to my car I realized that if she had been in town, it would have been unthinkable that she wouldn’t have called me back. It had been two weeks; something was wrong.

Strangely, this thought buoyed me as I headed for home. When I left the house every morning, I just let my parents assume that I was meeting up with Sloane, and if they asked what my plans were, I said vague things about applying for jobs. But I knew now was the moment to tell them that I was worried; that I needed to know what had happened. After all, maybe they knew something, even though my parents weren’t close with hers. The first time they’d met, Milly and Anderson had come to collect Sloane from a sleepover at my house, two hours later than they’d been supposed to show up. And after pleasantries had been exchanged and Sloane and I had said good-bye, my dad had shut the door, turned to my mother, and groaned, “That was like being stuck in a Gurney play.” I hadn’t known what he’d meant by this, but I could tell by his tone of voice that it hadn’t been a compliment. But even though they hadn’t been friends, they still might know something. Or they might be able to find something out.

I held on to this thought tighter and tighter as I got closer to my house. We lived close to one of the four commercial districts scattered throughout Stanwich. My neighborhood was pedestrian-friendly and walkable, and there was always lots of traffic, both cars and people, usually heading in the direction of the beach, a ten-minute drive from our house. Stanwich, Connecticut, was on Long Island Sound, and though there were no waves, there was still sand and beautiful views and stunning houses that had the water as their backyards.

Our house, in contrast, was an old Victorian that my parents had been fixing up ever since we’d moved in six years earlier. The floors were uneven and the ceilings were low, and the whole downstairs was divided into lots of tiny rooms—originally all specific parlors of some kind. But my parents—who had been living, with me, and later my younger brother, in tiny apartments, usually above a deli or a Thai place—couldn’t believe their good fortune. They didn’t think about the fact that it was pretty much falling down, that it was three stories and drafty, shockingly expensive to heat in the winter and, with central air not yet invented when the house was built, almost impossible to cool in the summer. They were ensorcelled with the place.

The house had originally been painted a bright purple, but had faded over the years to a pale lavender. It had a wide front porch, a widow’s walk at the very top of the house, too many windows to make any logical sense, and a turret room that was my parents’ study.

I pulled up in front of the house and saw that my brother was sitting on the porch steps, perfectly still. This was surprising in itself. Beckett was ten, and constantly in motion, climbing up vertiginous things, practicing his ninja moves, and biking through our neighborhood’s streets with abandon, usually with his best friend Annabel Montpelier, the scourge of stroller-pushing mothers within a five-mile radius. “Hey,” I said as I got out of the car and walked toward the steps, suddenly worried that I had missed something big in the last two weeks while I’d sleepwalked through family meals, barely paying attention to what was happening around me. But maybe Beckett had just pushed my parents a little too far, and was having a time-out. I’d find out soon enough anyway, since I needed to talk to them about Sloane. “You okay?” I asked, climbing up the three porch steps.

He looked up at me, then back down at his sneakers. “It’s happening again.”

“Are you sure?” I crossed the porch to the door and pulled it open. I was hoping Beckett was wrong; after all, he’d only experienced this twice before. Maybe he was misreading the signs.

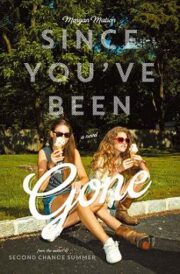

"Since You’ve Been Gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Since You’ve Been Gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Since You’ve Been Gone" друзьям в соцсетях.