“Though it might be said, guv, that it never was that anytime during the last thirty years or so,” Peters could not resist adding.

Thomas muttered darkly to the effect that there would be nothing wrong with his carriage if a certain impudent young ’un, who would remain nameless for the sake of peace, had not passed it when he didn’t ought and then stopped dead in front of it in the middle of the road. And in his day, he added, carriages were made to last.

If Thomas’s coach had not been moving so slowly that it was almost going backward, Peters retorted, and if at that pace it could not stop behind another carriage without slithering into a snowbank, then it was high time a certain coachman who would remain nameless was put out to grass.

Lucius left them to it without attempting any mediation and went back inside the inn and into the kitchen. Frances was in there, busy getting breakfast.

Knowledge hit him like a fist to the stomach. He had been holding that slender body naked in his arms not so long ago.

“If you wish,” he said after giving her the bad news about her own carriage, “we will both remain here another day. It will surely be rescued and roadworthy by tomorrow.”

The suggestion certainly had its appeal—except that the world would find them sometime during the course of the day even if they stayed here. Villagers would come for their ale. The Parkers would return from their holiday. There was no way of recapturing the charm of yesterday’s isolation—or the passion of last night’s.

Time had moved on as it always and inevitably did.

She hesitated, but he could almost read her mind as it turned over the same thoughts and came to the same conclusions.

“No,” she said. “I must get back to the school today somehow. The girls return today, and classes begin tomorrow. There is so much to do before then. I will see if a stagecoach stops somewhere in the village.”

She was not quite looking into his eyes, he noticed. But her face was flushed, and her lips looked soft and slightly swollen, and there was something more than usually warm and feminine about her whole demeanor. She looked like a woman who had been well and thoroughly bedded the night before.

He felt partly aroused again by the sight of her. But last night was over and done with, alas. It ought not to have happened at all, he supposed, though of course he had gone to some pains to see that it did happen. And to say that he had enjoyed the outcome would be to understate the case.

It was simply time to move on.

“There is none,” he said. “I have asked Wally. But if you are willing to leave Thomas here to take your carriage back where it came from tomorrow, you may come with me this morning. I’ll take you to Bath.”

She raised her eyes to his then, and her flush deepened.

“Oh, but I cannot ask that of you,” she said. “Bath must be well out of your way.”

It was. More than that, since yesterday could not be recaptured, he did not really want to prolong this encounter beyond its natural ending. It would have been best this morning if they could simply have kissed, bidden each other a cheerful farewell, and gone their separate ways. It would have all been over within an hour or so.

“Not very much out of the way,” he said. “And you did not ask it of me, did you? I think I ought to see you safely delivered to your school, Frances.”

“Because you feel responsible for what happened to my carriage?” she asked.

“Nonsense!” he said. “If Thomas were my servant, I would set him to digging about the flower beds in a remote corner of my park, where no one would notice if he pulled out the flowers and left the weeds. If he ever was competent at driving a carriage, it must have been at least twenty years ago.”

“He is a loyal retainer to my great-aunts,” she said. “You have no right to—”

He held up a staying hand and then strode toward her and kissed her hard on the mouth.

“I would love to have a good scrap with you again,” he said. “I remember you as a worthy foe. But I would rather not waste good traveling time. I want to take you to Bath in person so that I do not have to worry about your getting there safely.”

The roads might be passable, but there was no doubt that they would be dangerous. Snow, slush, mud—whichever they were fated to encounter, and it seemed probable that it would be all three before the journey was ended—the going would be difficult. He would worry about her if he knew she was alone with the elderly Thomas driving her more-than-elderly carriage. Even tomorrow the roads would not be at their best.

Good Lord! he thought suddenly. He had not gone and fallen in love with the woman, had he? That would be a deuced stupid thing to do.

He had just promised his grandfather that he would begin seriously courting a suitable bride—and a suitable bride in his world meant someone with connections to the aristocracy, someone who had been brought up from the cradle to fill just such a role as that of Countess of Edgecombe.

Someone perfect in every way.

Someone like Portia Hunt.

Not someone like a schoolteacher from Bath who taught music and French.

It was a harsh reality but a reality nonetheless. It was the way his world worked.

“I would be very grateful, then,” she said, turning away to finish cooking their breakfast. “Thank you.”

She was cool and aloof this morning—except for the flushed cheeks and swollen lips. He wondered if she regretted last night, but he would not ask her. There was no point in regretting what was done, was there? And she had certainly not been regretting it while it was happening. She had loved with hunger and enthusiasm—a thought he had better not pursue further.

He wished there were a stagecoach coming through the village. He needed to get away from her.

But less than an hour later, having eaten and washed the dishes and left money and instructions with Thomas and a generous payment with Wally for their stay at the inn, Lucius’s carriage set out on its way to Bath with Frances Allard as a passenger.

There had been some argument, of course, over who should make the payments. He had prevailed, but he knew that giving in had been painful, even humiliating, to her. If his guess was correct—and he was almost certain it was—her reticule did not contain vast riches. Her pride was doubtless stung. She sat in stiff silence for the first mile or two, looking out through the window beside her.

Lucius found himself wishing again that they could relive yesterday—just exactly as it had been except perhaps for the afternoon, which they had wasted by spending apart in a vain attempt to avoid what had probably been inevitable from the moment of their meeting. It must be years since he had frolicked as he had with her out in the snow just for the simple enjoyment of frolicking. It was years since he had danced voluntarily. Indeed, he did not believe he had ever done so before last evening. And he still felt relaxed and satiated after a night of good, vigorous sex.

Damnation, but he was not ready to say good-bye to her yet.

And why should he say it? The Season would not begin in any earnest until after Easter. There was not much he could do about fulfilling his promise until then. And despite what his mother and sisters seemed to believe, he had not yet committed himself to Portia Hunt. In fact, he had always been very careful in her presence and in that of Balderston, her father, and most especially in that of Lady Balderston not to commit himself in any way, not to say anything that might be construed as a marriage offer. He had not even promised his grandfather that she would be the one.

Honor was not at stake here, then. Not yet, anyway. He had not been unfaithful to anyone last night.

Why should he say good-bye?

He was rationalizing, of course. He knew that. There was no realistic future for him and Frances Allard. But he went on trying to devise one anyway.

He had little experience with not getting whatever he wanted.

Why could there not have been a stagecoach passing through the village?

Or why could she not simply have said that she would wait alone for her great-aunts’ carriage to be ready tomorrow? But he would not, she was sure, have been willing to leave her alone at the inn. And, truth to tell, she could not have borne to be left alone there, to watch his carriage drive away from the inn and disappear to view. The emptiness of the inn, the silence, would have been unbearable.

It was what would happen in Bath, though. The thought caused a painful churning of her stomach that made her sorry she had eaten any breakfast.

The best solution, of course, would have been to say good-bye this morning after breakfast and to have both left in a different carriage—to go in the same direction for a while. His carriage would soon have outpaced hers, though. Anyway, that had not been an option.

Ah, there was no easy way to say good-bye.

What on earth had possessed her last night? She had never come close to giving in to such temptation before.

She had given herself to a stranger. She had made love with him and spent all night in bed with him. They had coupled three separate times, the third time hot and swift and wonderful just before he got up and left her room, wearing only his pantaloons and carrying the rest of his clothes.

And now she was going to have to suffer all the considerable emotional consequences. She was already suffering them even though she was still with him. She could feel his body close to hers on the carriage seat. She could feel his body heat down her right side. But it was the end. Soon—at the end of this slow, dreary journey past snow fields that looked gray rather than pristine white today—soon they would be saying good-bye, and she would never see him again.

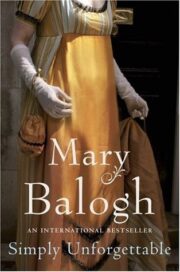

"Simply Unforgettable" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Simply Unforgettable". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Simply Unforgettable" друзьям в соцсетях.