“Quit worrying about it,” John told him.

Georgeanne knew next to nothing about hockey. “What’s a hat trick?”

“It’s when a player scores three goals in one game,” Ernie explained. “And I missed that damn Kings game, too.” He paused to shake his head, his eyes filling with pride as he gazed at his grandson. “That candy-assed Gretzky rode the pines for a good fifteen minutes after you checked him into the boards,” he said, genuinely delighted.

Georgeanne didn’t have the faintest idea what Ernie was talking about, but getting “checked into the boards” sounded painful to her. She’d been born and raised in a state that lived for football, yet she hated it. She sometimes wondered if she was the only person in Texas who abhorred violent sports. “Isn’t that bad?” she asked.

“Hell no!” the older man exploded. “He went up against The Wall and lived to regret it.”

One corner of John’s mouth lifted upward, and he smashed several crackers into his chowder. “I guess I won’t be winning the Lady Bying any time soon.”

Ernie turned to Georgeanne. “That’s the trophy given for gentlemanly conduct, but screw that.” He pounded the table with one fist and raised his spoon to his mouth with the other.

Personally, Georgeanne didn’t think either of them was in danger of winning an award for gentlemanly conduct. “This is wonderful chowder,” she said in an effort to change the subject to something a little less volatile. “Did you make it?”

Ernie reached for the beer next to his bowl. “Sure,” he answered, and raised the bottle to his mouth.

“It’s delicious.” It had always been important to Georgeanne that people like her-never more than now. She figured her friendly overtures were wasted on John, so she turned her considerable charm on his grandfather. “Did you start with a white sauce?” she asked, looking into Ernie’s blue eyes.

“Yeah, sure, but the trick to good chowder is in the clam juice,” he informed her, then between bites, he shared his recipe with Georgeanne. She gave him the appearance of hanging on his every word, of concentrating on him fully, and within seconds, he dropped into the palm of her hand like a ripe plum. She asked questions and commented on his choice of spices, and all the while she was very aware of John’s direct gaze. She knew when he took a bite, raised the beer bottle to his lips, or wiped his mouth with a napkin. She was aware when he shifted his gaze from her to Ernie and back again. Earlier, when he’d woken her from her nap, he’d been almost friendly. Now he seemed withdrawn.

“Did you teach John how to make chowder?” she asked, making an effort to pull him into the conversation.

John leaned back in his chair and crossed his arms over his chest. “No,” was all he said.

“When I’m not here, John goes out to eat. But when I am here, I make sure his kitchen is good and stocked. I like to cook,” Ernie provided. “He doesn’t.”

Georgeanne smiled at him. “I truly believe that people are born either hating it or loving it, and I can just tell that you”-she paused to touch his wrinkled forearm-“have a God-given talent. Not everyone can make a decent white sauce.”

“I could teach you,” he offered with a smile.

His skin felt like warm waxed paper beneath her touch, filling her heart with warm childhood memories. “Thank you, Mr. Maxwell, but I already know how. I’m from Texas and we cream everything, even tuna.” She glanced at John, noticed his frown, and decided to ignore him. “I can make gravy out of just about anything. My grandmother was famous for her redeye, and I’m not talking about a late-night flight, if you know what I mean. When one of our friends or relatives took their final journey to heaven, it was understood that my grandmother would bring the ham and redeye gravy. After all, Grandmother was raised on a hog farm near Mobile, and she was famous on the funeral circuit for her honeyed hams.” Georgeanne had spent her life around elderly people, and talking to Ernie felt so comfortable she leaned closer to him and her smile brightened naturally. “Now, my aunt Lolly is famous as well, but unfortunately not in a flattering way. She’s known for her lime Jell-O because she’ll throw anything into the mold. She got really bad when Mr. Fisher took his final journey. They’re still talking about it at First Missionary Baptist, which in no way should be confused with the First Free Will Baptists, who used to foot-wash, but I don’t believe they practice-”

“Jeez-us,” John interrupted. “Is there a point to any of this?”

Georgeanne’s smile fell, but she was determined to remain pleasant. “I was getting to it.”

“Well, you might want to do that real soon because Ernie isn’t getting any younger.”

“Stop right there,” his grandfather warned.

Georgeanne patted Ernie’s arm and looked into John’s narrowed eyes. “That was incredibly rude.”

“I get a lot worse.” John pushed his empty bowl aside and leaned forward. “The guys on the team and I want to know, can Virgil still get it up, or was it strictly his money?”

Georgeanne could feel her eyes widen and her cheeks burn. The idea that her relationship with Virgil had been fodder for locker-room jock talk was beyond humiliating.

“That’s enough, John,” Ernie ordered. “Georgie is a nice girl.”

“Yeah? Well, nice girls don’t sleep with men for their money.”

Georgeanne opened her mouth, but words failed her. She tried to think of something equally hurtful, but she couldn’t. She was sure a perfectly witty and sarcastic response would come to her later, long after she needed it. She took a deep breath and tried to stay calm. It was a sad fact of her life that when she became flustered, words flew from her head-simple words like door, stove, or-as was the case earlier when she’d had to ask John for help-corset. “I don’t know what I’ve done to make you say such cruel things,” she said, placing her napkin on the table. “I don’t know if it’s me, if you hate women in general, or if you’re just terminally bad-tempered, but my relationship with Virgil is none of your business.”

“I don’t hate women,” John assured her, then deliberately lowered his gaze to the front of her T-shirt.

“That’s right,” Ernie broke in. “Your relationship with Mr. Duffy isn’t our business.” Ernie reached for her hand. “The tide is almost out. Why don’t you go on down and look for some tide pools near those big rocks down there. Maybe you can find something from the Washington coast to take back to Texas with you.”

Georgeanne had been raised to respect her elders too much to argue or question Ernie’s suggestion. She glanced at both men, then stood. “I’m truly sorry, Mr. Maxwell. I didn’t mean to cause trouble between y’all.”

Without taking his eyes from his grandson, Ernie answered, “It’s not your fault. This has nothing to do with you.”

It certainly felt like her fault, she thought as she stepped behind her chair and slid it forward. As Georgeanne walked through the narrow, foam green kitchen toward the multipaned back door, she realized that she’d let John’s good looks impair her judgment. He wasn’t pretending to be a jerk. He was one!

Ernie waited until he heard the back door close before he said, “It’s not right for you to take out your bad temper on that little girl.” He watched one brow rise up his grandson’s forehead.

“Little?” John planted his elbows on the table. “By no stretch of the imagination could you ever mistake Georgeanne for a ‘little girl.’ ”

“Well, she can’t be very old,” Ernie continued. “And you were disrespectful and rude. If your mother were here, she’d give your ear a good hard twist.”

A smile curved one corner of John’s mouth. “Probably,” he said.

Ernie stared into his grandson’s face and pain wrenched his heart. The smile on John’s lips didn’t reach his eyes-it never did these days. “It’s no good, John-John.” He placed his hand on John’s shoulder and felt the hard muscles of a man. Before him, he recognized nothing of the happy boy he’d taken hunting and fishing, the boy he’d taught to play hockey and drive a car, the boy he’d taught everything he’d known about being a man. The man before him wasn’t the boy he’d raised. “You have to let it out. You can’t hold it all in, walking around blaming yourself.”

“I don’t have to let anything out,” he said, his smile disappearing altogether. “I told you that I don’t want to talk about it.”

Ernie looked into John’s closed expression, into the blue eyes so much like his own had been before they’d clouded with age. He’d never pressed John about his first wife. He’d figured John would come to terms with what Linda had done on his own. Even though John had been a dumbass and married that stripper six months ago, Ernie had hopes that he’d begun to work things out in his own mind. But tomorrow marked the first anniversary of her death, and John seemed just as angry as the day he’d buried her. “Well, I think you need to talk to someone,” Ernie said, deciding that maybe he should force the issue for John’s own good. “You can’t keep it up, John. You can’t pretend nothing happened, yet at the same time drink to forget what did.” He paused to remember what he’d heard on the television the other day. “You can’t use booze to self-medicate. Alcohol is just a symptom of a greater disease,” he said, pleased that he remembered.

“Have you been watching Oprah again?”

Ernie frowned. “That isn’t the point. What happened is eating a hole in you, and you’re taking it out on an innocent girl.”

John leaned back in his chair and folded his arms over his chest. “I’m not taking anything out on Georgeanne.”

“Then why were you so rude?”

“She gets on my nerves.” John shrugged. “She rambles on and on about absolutely nothing.”

“That’s because she’s a southerner,” Ernie explained, letting the subject of Linda drop. “You just have to sit back and enjoy a southern gal.”

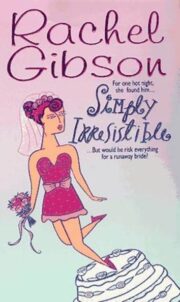

"Simply Irresistible" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Simply Irresistible". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Simply Irresistible" друзьям в соцсетях.