God, human beings are resilient, Connie thought.

We are resilient!

Dan filleted the bass, and Connie set out cheese and crackers on a plate. Toby and Meredith were sitting side by side on the blanket, not touching, not talking, but they were definitely coexisting more peacefully now. Or was she imagining this?

It was high school over and over and over again.

There was a noise. Connie looked up to see a forest-green pickup truck coming their way. Although it had been a nearly perfect day, they had seen very few people-a couple of lone fishermen on foot, a handful of families in rental Jeeps who approached their spot then backed up, for fear of infringing. But this truck drove toward the camp, then stopped suddenly, spraying sand on Toby and Meredith’s blanket. There was white writing on the side of the truck. Trustees of the Reservation. A man poked his head out the window. He was wearing a green cap. It was Bud Attatash.

He stepped out of the truck. “You folks doing all right?”

Dan was monitoring the progress of the striped bass on the grill. He said, “We’re doing great, Bud. Couldn’t have asked for a better day.”

“I’ll agree with you there,” Bud said. He stood with his hands in his pockets, an uncomfortable air about him. He hadn’t come to talk about the weather. Was he upset about the grill? Or about the fire? Dan had gotten a fire permit; it was in the glove compartment of the Jeep. Was he going to scold them for having an open container? One open beer?

“You headed home?” Dan asked. He had explained that, as ranger, Bud Attatash spent the summer living in a cottage out here on the point.

“Yep,” Bud said. “I just wanted to stop by and see how you folks were doing.”

“We’re cooking up this striped bass,” Dan said. “It was legal, half inch over.”

“They’ve been big this summer,” Bud said. He cleared his throat. “Listen, after you folks headed out, I got to thinking about what you said about that dead seal on the south shore being a more complicated issue than it appeared. So I called up Chief Kapenash, and he told me about it. He said that you, Dan, were a part of that whole thing.” Here, he looked, not at Dan, but at Meredith, whose face had gone scary blank. “And I realized that I said some inappropriate things.” He nodded at Meredith. “Are you Mrs. Delinn?”

Meredith stared. Toby said, “Please, sir, if you don’t mind…”

“Well, Mrs. Delinn, I just want to apologize for my callous words earlier. And for perhaps sounding like I cared more about a dead seal than I did for your welfare. What those people did was inexcusable. No doubt, you’ve been through enough in your private life without these hooligans trying to scare you.”

Meredith pressed her lips together. Toby said, “That’s right, you’re right, she’s been through enough.”

“So if anyone ever bothers you again, you let me know.” He gazed out over the dark water at the twinkling lights of town. “Nantucket is supposed to be a safe haven.”

Dan came over to shake Bud’s hand. “Thanks, Bud. Thank you for coming all the way out here to say that. You didn’t have to.”

“Oh, I know, I know,” Bud said. “But I didn’t want any of you to get the wrong idea about me. I’m not coldhearted or vindictive.”

“Well, thanks again,” Dan said. “You have a good night.”

Bud Attatash tipped his cap at Meredith and then again at Connie, and then he climbed into his truck and drove off into the darkness.

“Well,” Meredith said after a minute. “That was a first.”

They ate the grilled fish with some sliced fresh tomatoes that Dan had gotten at Bartlett’s Farm. Then they each put a marshmallow on a stick and roasted it over the fire. Meredith went back in the water, and Toby stood to join her, but Meredith put a hand up and said, “Don’t even think about it.” Toby plopped back down on his towel. “Yeah,” he said. “She wants me.” Connie climbed into Dan’s lap and listened to the splashing sound of Meredith swimming. Dan kissed her and said, “Let’s get out of here.”

Yes! she thought.

She and Dan started breaking down the camp and packing everything up. Meredith emerged from the water with her teeth chattering, and Connie handed her the last dry towel. She collected the trash and stowed everything in the coolers. She folded up the blankets and the chairs while Dan dealt with the cooling grill and doused the fire. Toby put away the fishing poles, and Meredith collected the horseshoes. A seagull landed for the remains of the striped bass. Connie found the plastic bat in the sand and tucked it into the back of the Jeep. The Wiffle ball was still out there somewhere, Connie thought, tucked into the eelgrass like a seagull’s egg, a memento of one of the small triumphs of the day.

The days zipped by. Connie spent nearly every night at Dan’s house. She left a toothbrush there, and she bought half-and-half for her coffee (Dan, health nut, had only skim milk) and kept it in the fridge. She had met both of Dan’s younger sons-Donovan and Charlie-though they had little more to say to her than “Hey.” Dan relayed the funny things they said to him after Connie left.

Donovan, who was sixteen, had said, “Glad you’re getting laid on a regular basis again, Dad. Can I borrow the Jeep?”

Charlie, the youngest, said, “She’s pretty hot for an older lady.”

“Older lady!” Connie exclaimed.

“Older than him, he means,” Dan said. “And he’s fourteen.”

On the days that Dan had to work, Connie and Meredith and Toby walked the beach and then sat on the deck and read their books and discussed what they wanted to do for dinner. These were the moments when Toby acted like an adult. But more and more often, there were moments when Toby acted like an adolescent. He would mess up Meredith’s hair or throw stones at the door of the outdoor shower while she was in there, or he would steal her glasses, forcing her to come stumbling blindly after him.

“Look at you,” he’d say to her. “You’re chasing me.”

Connie said to Dan, “I can’t tell if that’s going to happen or not.”

Toby asked if he could stay another week.

“Another week?” Connie said. “Or longer?”

“I don’t start at the Naval Academy until after Labor Day,” he said.

“So what does that mean?” Connie asked. “You’ll stay until Labor Day?”

“Another week,” Toby said. “But maybe longer. If that’s okay with you?”

“Of course, it’s okay with me,” Connie said. “I’m just wondering what I did to deserve the honor of your extended presence?” What she wanted him to say was that he was staying because of Meredith.

“This is Nantucket,” Toby said, “Why would I want to be anywhere else?”

MEREDITH

On the morning of the twenty-third of August, Meredith was awakened by the phone. Was it the phone? She thought it was, but the phone was in Connie’s room, far, far away, and Meredith was in the grip of a heavy, smothering sleep. Connie would answer it. The phone kept ringing. Really? Meredith tried to lift her head. The balcony doors were shut tight-even with Toby across the hall, she didn’t feel safe enough to sleep with them open-and her room was sweltering. She couldn’t move. She couldn’t answer the phone.

A little while later, the phone rang again. Meredith woke with a start. Connie would get it. Then she remembered that Connie wasn’t home. Connie was at Dan’s.

Meredith got out of bed and padded down the hall. Toby probably hadn’t even heard the phone; he slept like a corpse. Meredith liked to believe this was a sign that he had a clean conscience. Freddy had jolted awake at the slightest sound.

Connie didn’t have an answering machine, and so the phone rang and rang. It’s probably Connie, Meredith thought, calling from Dan’s house with some kind of plan for the day-a lunch picnic at Smith’s Point or a trip to Tuckernuck in Dan’s boat. Meredith’s heart quickened. She had fallen in love with Nantucket-and yet in a few weeks, she would have to leave. She was trying not to think about where she would go or what she would do.

The caller ID said, NUMBER UNAVAILABLE, and Meredith’s brain shouted out a warning, even as she picked up the phone and said hello.

A female voice said, “Meredith?”

“Yes?” Meredith said. It wasn’t Connie, but the voice sounded like she knew her, and Meredith thought, Oh, my God. It’s Ashlyn!

The voice said, “This is Rae Riley-Moore? From the New York Times?”

Meredith was confused. Not Ashlyn. Someone else. Someone selling something? The paper? The voice sounded familiar to Meredith because that was how telemarketers did it now; they acted like you were an old friend. Meredith held the phone in two fingers, ready to drop it like a hot potato.

“I’m sorry to bother you at home,” Rae Riley-Moore said.

At home. This wasn’t Meredith’s home. If this was a telemarketer, she wouldn’t have asked for Meredith. She would have asked for Connie.

Meredith said nothing. Rae Riley-Moore was undeterred.

“And so early. I hope I didn’t wake you.”

Meredith swallowed. She looked down the hall to the closed door of Toby’s room. He would still be fast asleep. But a few days ago, he’d said, If you need to come into this room for any reason, just walk right in. I am here for you, Meredith. Whatever you need.

At the time she had thought, Here for me? Ha!

Meredith said, “I’m sorry. What can I do for you?”

“I’m calling about the news that broke this morning?” Rae Riley-Moore said. “In regard to your husband?”

Meredith spoke without thinking. “Is he dead?” Suddenly, the world stopped. There was no bedroom, no old boyfriend, no beautiful island, no $50 billion Ponzi scheme. Meredith was suspended in a white-noise vacuum, waiting for an answer to come through the portal that was the phone in her hand.

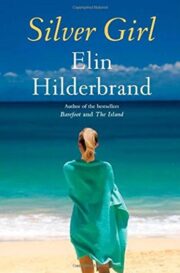

"Silver Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Silver Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Silver Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.