Meredith didn’t move or speak for what seemed like a long time, but then, Connie watched her exhale. She relaxed her grip on the duffel bag and let Connie take it from her. Connie said, “I want you to come see what Dan the power-washer guy looks like.” And she led Meredith to the window.

MEREDITH

Connie came home from the hospital thrift shop a few days later with a dark wig for Meredith, styled in two long pigtails. When Meredith tried it on, she looked like Mary Ann from Gilligan’s Island.

“It’s awful,” Meredith said.

“Awful,” Connie agreed. “But that’s a good thing. We want mousy, and we want anonymous. And we need to do something about your glasses.”

“I love my glasses,” Meredith protested. “I’ve had my glasses since the eighth grade.”

“I know,” Connie said. “I remember the day you got them. But now, they have to go. We aren’t going to stay inside all summer, and we aren’t going to have you accosted by haters, and so you need to travel incognito. The glasses are a dead giveaway. When women dress up as Meredith Delinn for Halloween, they’ll be wearing those glasses.”

“Are women going to dress up as me for Halloween?” Meredith said.

Connie smiled sadly. “The glasses have to go.”

Connie took Meredith’s glasses to Nantucket Eye Center and had a new pair made. While Connie was gone with her glasses, Meredith was left helplessly blind. She desperately wanted to go outside and sit on the deck, but she was terrified to do so without Connie around. She lay upstairs on her bed, but she couldn’t read without her glasses. She stared at the blurry surrounds of the pink guest room.

She was still back on the Main Line in the 1970s with her father and Toby.

Meredith’s parents had been stunned when she told them about her date with Toby. For Chick Martin, the surprise had been mixed with something else. Jealousy? Possessiveness? Meredith feared her father would react the same way that Connie had. But he rose above whatever qualms he had about Meredith’s burgeoning womanhood and acted the role of protective father. When Toby arrived on that first evening to pick Meredith up, Chick asked, “Do you have a clean driving record?”

“Yes, sir,” Toby said.

“You will have Meredith home by eleven, please.”

“Yes, sir, Mr. Martin,” Toby said.

It took Chick a few months to adjust to Meredith’s new persona. Meredith was the same on the outside-studious, obedient, loving toward both her parents, respectful of their rules, grateful for all they did for her-but something had changed. To her father, she supposed, it seemed like she was now focused on Toby. But really, she was focused on herself-her body, her emotions, her sexuality, her capacity to love someone other than her parents.

Whoa! Meredith couldn’t remember ever feeling as alive as she had that summer she turned sixteen, when her romance with Toby raged in her like a fire. She was hot for him-that had been the popular turn of phrase at the time. Many times they skipped the movies and drove to Valley Forge Park and made out in the car. They touched each other through their clothes, and then the clothes started coming off in stages. And then arrived a night when Meredith was naked and Toby had his jeans at his knees and Meredith straddled him and… he stopped her. It was too soon, she was young, it wasn’t time yet. Meredith had cried-partly out of sexual frustration, partly out of anger and jealousy. Toby had had sex with Divinity Michaels and Ravi from Bryn Mawr and probably also the French teacher, Mademoiselle Esme (though Meredith had never been brave enough to ask him)-so why not her?

“This is different,” he said. “This is special. I want to take it slow. I want it to last.”

“Plus,” he said, “I’m afraid of your father.”

“Afraid of my father?” Meredith wailed.

“He spoke to me,” Toby said. “He asked me to respect you. He told me to be a gentleman.”

“A gentleman?” Meredith said. She huddled, shivering, against the passenger-side door. The vinyl seats of the Nova were cold. She hunted for her underwear. She didn’t want a gentleman. She wanted Toby.

Meredith went on a campaign to keep her father and Toby away from each other. But then Chick invited Toby over to help burn the piles of leaves in the yard, then go inside and watch Notre Dame trounce Boston College, and eat pigs in a blanket that Meredith’s mother served along with a dish of spicy brown mustard. At the holidays, Toby was invited to the Martins’ annual Christmas party, which was so crowded with reveling adults that Meredith was certain there would be an opportunity to sneak to her bedroom. But Toby would not be coerced upstairs.

Toby was also invited over on New Year’s eve, a night that Meredith had traditionally spent alone with her parents. They always ate dinner at the General Wayne Inn and always saw a movie at the cinemas in Frazer, then they always returned home for a bottle of Tattinger champagne (Meredith had been given her first sip at age thirteen) and chocolate truffles while watching Dick Clark in Times Square on TV. Toby came along for all of it-the dinner, the movie, the champagne, the chocolates, and the ball dropping at midnight. At twelve fifteen, Chick shook Toby’s hand and said, “I want you out of this house in one hour. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’m not coming back down, so I’ll need your word.”

“You have my word, sir.”

“Very good,” Chick said. “Please tell your parents we say ‘happy New Year.’ ” And he closed the door to the library with a click.

Meredith remembered sitting still as a statue on the library sofa, holding her breath, believing that it was some kind of trick. But then she heard her parents’ footsteps on the stairs and their footsteps treading down the second floor hall above them. They were going to bed, leaving Toby and Meredith in the plush comfort of the library for a whole hour.

Toby approached the sofa cautiously. Meredith pulled him down on top of her.

Toby said, “Meredith, stop.”

Meredith said, “He basically gave you his permission.” She would not be deterred. It was a new year, and she was going to lose her virginity-not in the front seat of Toby’s ’69 Nova, and not in the grass of Valley Forge Park-but right here in her own house by the library fire.

Quietly.

In the spring, Toby graduated, but because he had underperformed on his SATs, he took a year off to boost his prospects for college. During the summer, he and Meredith went to the O’Briens’ summer house in Cape May, where they sailed every day and hung out on the boardwalk at night eating chili dogs and kettle corn. They had their picture taken in a photo booth and kept the strips in the back pockets of their jeans. They bought matching white rope bracelets.

In the fall, Toby took two classes at Delaware County Community College and worked as a waiter at Minella’s Diner. He was around for everything Meredith’s senior year, and although Meredith’s parents grew concerned-was it a good idea for Meredith to be so serious about someone in high school?-they had no grounds for complaint. Meredith was at the top of her class at Merion Mercy, and she was placing first and second in all her diving competitions. She was a National Merit finalist, and everything else besides.

Because he worked at Minella’s, Toby was sometimes the one who delivered the subs to the Martin house for Chick’s monthly poker games, and one night, Chick invited Toby to come back after his shift and join the game. This night fostered a new bond between Chick and Toby; Meredith figured her father either liked Toby, or he was embracing the if-you-can’t-beat-’em-join-’em philosophy. Chick invited Toby down to his law offices, and the two of them went out for lunch at the City Tavern. He took Toby and Meredith to Sixers games. He and Deidre and Toby and Meredith went to see the lights at Longwood Gardens at Christmastime, they went to hear the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Academy of Music, they went out to dinner at Bookbinders and to brunch at the Green Room in the Hotel du Pont.

“You do all this old-people stuff,” Connie said. “How do you stand it?”

“We like it,” Meredith said. She refrained from telling Connie that what she wanted most in the world was to marry Toby. She pictured the two of them having kids and settling down on the Main Line, in a life not so different from that of her own parents.

To this day, Meredith couldn’t explain how the whole thing fell apart, but fall apart it did.

Toby broke up with Meredith on the night of her high-school graduation. The O’Briens threw a huge party for Connie; the party was tented and catered and there was free-flowing alcohol for the adults, which inevitably trickled down to the teenagers. Toby was drinking Coke and Wild Turkey, but because Meredith’s parents were in attendance, she was sipping lukewarm Tab. Connie was drinking gin and tonics like her mother. She had given up on her romance with Matt Klein and was now dating the star of the Radnor lacrosse team, Drew Van Dyke, who was headed to Johns Hopkins in the fall. Connie and Drew disappeared from the party at ten o’clock, and Toby wanted to ditch, too-he suggested skinny-dipping in the pool at Aronimink, then making love on the rolling hill behind the ninth tee. But this was too dangerous for Meredith; Chick was the president of the board at Aronimink, and if Meredith and Toby got caught, her father would be humiliated, which wasn’t something Meredith was willing to risk. She told Toby she wanted to stay and dance to the band.

Toby said, “What are you, a hundred years old?”

It was true that the people remaining at the party were all older, friends of Bill and Veronica O’Brien.

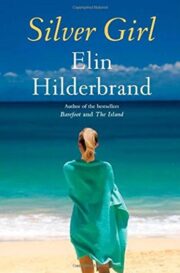

"Silver Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Silver Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Silver Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.