The Junipero Serra Catholic Academy, grades K-12, had been made co-educational in the eighties, and had, much to my relief, recently dropped its strict uniform policy. The uniforms had been royal blue and white, not my best colors. Fortunately, the uniforms had been so unpopular that they, like the boys-only rule, had been abandoned, and though the pupils still couldn't wear jeans, they could wear just about anything else they wanted. Since all I wanted was to wear my extensive collection of designer clothing – purchased at various outlet stores in New Jersey with Gina as my fashion coordinator – this suited me fine.

The Catholic thing, though, was going to be a problem. Not really a problem so much as an inconvenience. You see, my mother never really bothered to raise me in any particular religion. My father was a non-practicing Jew, my mother Christian. Religion had never played an important part in either of my parents' lives, and, needless to say, it had only served to confuse me. I mean, you would think I'd have a better grasp on religion than anybody, but the truth is, I haven't the slightest idea what happens to the ghosts I send off to wherever it is they're supposed to go after they die. All I know is, once I send them there, they do not come back. Not ever. The end.

So when my mother and I showed up at the Mission School's administrative office the Monday after my arrival in sunny California, I was more than a little taken aback to be confronted with a six foot Jesus hanging on a crucifix behind the secretary's desk.

I shouldn't have been surprised, though. My mom had pointed out the school from my room on Sunday morning as she helped me to unpack. "See that big red dome?" she'd said. "That's the Mission. The dome covers the chapel."

Doc happened to be hanging around – I'd noticed he did that a lot – and he launched into another one of his descriptions, this time of the Franciscans, who were members of a Roman Catholic religious order that followed the rule of St. Francis, approved in 1209. Father Junipero Serra, a Franciscan monk, was, according to Doc, a tragically misunderstood historical figure. A controversial hero in the Catholic church, he had been considered for sainthood at one time, but, Doc explained, Native Americans questioned this move as "a general endorsement of the exploitative colonization tactics of the Spanish. Though Junipero Serra was known to have argued on behalf of the property rights and economic entitlement of converted Native Americans, he consistently advocated against their right to self-governance, and was a staunch supporter of corporal punishment, appealing to the Spanish government for the right to flog Indians."

When Doc had finished this particular lecture, I just looked at him and went, "Photographic memory much?"

He looked embarrassed. "Well," he said. "It's good to know the history of the place where you're living."

I filed this away for future reference. Doc might be just the person I needed if Jesse showed up again.

Now, standing in the cool office of the ancient building Junipero Serra had constructed for the betterment of the natives in the area, I wondered how many ghosts I was going to encounter. That Serra guy had to have a bunch of Native Americans mad at him – particularly considering that corporal punishment thing – and I hadn't any doubt I was going to encounter all of them.

And yet, when my mom and I walked through the school's wide front archway into the courtyard around which the Mission had been constructed, I didn't see a single person who looked as if he or she didn't belong there. There were a few tourists snapping pictures of the impressive fountain, a gardener working diligently at the base of a palm tree – even at my new school there were palm trees – a priest walking in silent contemplation down the airy breezeway. It was a beautiful, restful place – especially for a building that was so old, and had to have seen so much death.

I couldn't understand it. Where were all the ghosts?

Maybe they were afraid to hang around the place. I was a little afraid, looking up at that crucifix. I mean, I've got nothing against religious art, but was it really necessary to portray the crucifixion so realistically, with so many scabs and all?

Apparently, I was not alone in thinking so, since a boy who was slumped on a couch across from the one where my mom and I had been instructed to wait noticed the direction of my gaze and said, "He's supposed to weep tears of blood if any girl ever graduates from here a virgin."

I couldn't help letting out a little bark of laughter. My mother glared at me. The secretary, a plump middle-aged woman who looked as if something like that ought to have offended her deeply only rolled her eyes, and said, tiredly, "Oh, Adam."

Adam, a good-looking boy about my age, looked at me with a perfectly serious face. "It's true," he said, gravely. "It happened last year. My sister." He dropped his voice conspiratorially. "She's adopted."

I laughed again, and my mother frowned at me. She had spent most of yesterday explaining to me that it had been really, really hard to convince the school to take me, especially since she couldn't produce any proof that I'd ever been baptized. In the end, they'd only let me in because of Andy, since all three of his boys went there. I imagine a sizeable donation had also played a part in my admittance, but my mother wouldn't tell me that. All she said was that I had better behave myself, and not hurl anything out of any windows – even though I reminded her that that particular incident hadn't been my fault. I'd been fighting with a particularly violent young ghost who'd refused to quit haunting the girls' locker room at my old school. Throwing him through that window had certainly gotten his attention, and convinced him to trod the path of righteousness ever after.

Of course, I'd told my mother that I'd been practicing my tennis swing indoors, and the racket had slipped from my hands – an especially unbelievable story, since a racket was never found.

It was as I was reliving this painful memory that a heavy wooden door opened, and a priest came out and said, "Mrs. Ackerman, what a pleasure to see you again. And this must be Susannah Simon. Come in, won't you?" He ushered us into his office, then paused, and said to the boy on the couch, "Oh, no, Mr. McTavish. Not on the first day of a brand new semester."

Adam shrugged. "What can I say? The broad hates me."

"Kindly do not refer to Sister Ernestine as a broad, Mr. McTavish. I will see to you in a moment, after I have spoken with these ladies."

We went in, and the principal, Father Dominic – that was his name – sat and chatted with us for a while, asking me how I liked California so far. I said I liked it fine, especially the ocean. We had spent most of the day before at the beach, after I'd finished unpacking. I had found my sunglasses, and even though it was too cold to swim, I had a great time just lying on a blanket on the beach, watching the waves. They were huge, bigger than on Baywatch, and Doc spent most of the afternoon explaining to me why that was. I forget now, since I was so drugged by the sun, I was hardly even listening. I found that I loved the beach, the smell of it, the seaweed that washed up on shore, the feel of the cool sand between my toes, the taste of salt on my skin when I got home. Carmel might not have had a Bagel Bob's, but Manhattan sure didn't have no beach.

Father Dominic expressed his sincere hope that I'd be happy at the Mission Academy, and went on to explain that even though I wasn't Catholic, I shouldn't feel unwelcome at Mass. There were, of course, Holy Days of Obligation, when the Catholic students would be required to leave their lessons behind and go to church. I could either join them, or stay behind in the empty classroom, whatever I chose.

I thought this was kind of funny, for some reason, but I managed to keep from laughing. Father Dominic was old, but what you'd probably call spry, and he struck me as sort of handsome in his white collar and black robes – I mean, handsome for a sixty-year-old. He had white hair, and very blue eyes, and well-maintained fingernails. I don't know many priests, but I thought this one might be all right – especially since he hadn't come down hard on the boy in the outer office who'd called that nun a broad.

After Father Dominic had described the various offenses I could get expelled for – skipping class too many times, dealing drugs on campus, the usual stuff – he asked me if I had any questions. I didn't. Then he asked my mother if she had any questions. She didn't. So then Father Dominic stood up and said, "Fine then. I'll say goodbye to you, Mrs. Ackerman, and walk Susannah to her first class. All right, Susannah?"

I thought it was kind of weird that the principal, who probably had a lot to do, was taking time out to walk me to my first class, but I didn't say anything about it. I just picked up my coat – a black wool trench by Esprit, trés chic (my mom wouldn't let me wear leather my first day of school) – and waited while he and my mother shook hands. My mom kissed me good-bye, and reminded me to find Sleepy at three, since he was in charge of driving me home – only she didn't call him Sleepy. Once again, a woeful lack of public transportation meant that I had to bum rides to and from school with my stepbrothers.

Then she was gone, and Father Dominic was walking me across the courtyard after having instructed Adam to wait for him.

"No prob, Padre," was Adam's response. He leered at me behind the father's back. It isn't often I get leered at by boys my own age. I hoped he was in my class. My mother's wishes for my social life just might be realized at last.

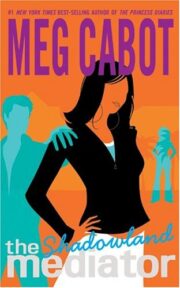

"Shadowland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Shadowland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Shadowland" друзьям в соцсетях.