Not here. Everybody here was just way calm.

And I guess I could see why. I mean, it didn't look to me like there was anything to get upset about. Outside, the sun was beating down on those palm trees I'd seen from the sky. There were seagulls – not pigeons, but actual big white and grey seagulls – scratching around in the parking lot. And when we went to get my bags, nobody even checked to see if the stickers on them matched my ticket stubs. No, everybody was just like, "Buh-bye! Have a nice day!"

Unreal.

Gina – she was my best friend back in Brooklyn; well, okay, my only friend, really – told me before I left that I'd find there were advantages to having three stepbrothers. She should know since she's got four – not steps, but real brothers. Anyway, I didn't believe her anymore than I'd believed people about the palm trees. But when Sleepy picked up two of my bags, and Dopey grabbed the other two, leaving me with exactly nothing to carry, since Andy had my shoulder bag, I finally realized what she was talking about: brothers can be useful. They can carry really heavy stuff, and not even look like it's bothering them.

Hey, I packed those bags. I knew what was in them. They were not light. But Sleepy and Dopey were like, No problem here. Let's get moving.

My bags secure, we headed out into the parking lot. As the automatic doors opened, everyone – including my mom – reached into a pocket and pulled out a pair of sunglasses. Apparently, they all knew something I didn't know. And as I stepped outside, I realized what it was.

It's sunny here.

Not just sunny, either, but bright – so bright and colorful, it hurts your eyes. I had sunglasses, too, somewhere, but since it had been about forty degrees and sleeting when I left New York, I hadn't thought to put them anywhere easily accessible. When my mother had first told me we'd be moving – she and Andy decided it was easier for her, with one kid and a job as a TV news reporter, to relocate than it would be for Andy and his three kids to do it, especially considering that Andy owns his own business – she'd explained to me that I'd love Northern California. "It's where they filmed all those Goldie Hawn, Chevy Chase movies!" she told me.

I like Goldie Hawn, and I like Chevy Chase, but I never knew they made a movie together.

"It's where all those Steinbeck stories you had to read in school took place," she said. "You know, The Red Pony."

Well, I wasn't very impressed. I mean, all I remembered from The Red Pony was that there weren't any girls in it, although there were a lot of hills. And as I stood in the parking lot, squinting at the hills surrounding the San Jose International Airport, I saw that there were a lot of hills, and the grass on them was dry and brown.

But dotting the hills were these trees, trees not like any I'd ever seen before. They were squashed on top as if a giant fist had come down from the sky and given them a thump. I found out later these were called cyprus trees.

And all around the parking lot, where there was evidently a watering system, there were these fat bushes with these giant red flowers on them, mostly squatting down at the bottom of these impossibly tall, surprisingly thick palm trees. The flowers, I found out, when I looked them up later, were hibiscus. And the strange looking bugs that I saw hovering around them, making a brrr-ing noise, weren't bugs at all. They were hummingbirds.

"Oh," my mom said when I pointed this out. "They're everywhere. We have feeders for them up at the house. You can hang one from your window if you want."

Hummingbirds that come right up to your window? The only birds that ever came up to my window back in Brooklyn were pigeons. My mom never exactly encouraged me to feed them.

My moment of joy about the hummingbirds was shattered when Dopey announced suddenly, "I'll drive," and started for the driver's seat of this huge utility vehicle we were approaching.

"I will drive," Andy said, firmly.

"Aw, Dad," Dopey said. "How'm I ever going to pass the test if you never let me practice?"

"You can practice in the Rambler," Andy said. He opened up the back of his Land Rover, and started putting my bags into it. "That goes for you, too, Suze."

This startled me. "What goes for me, too?"

"You can practice driving in the Rambler." He wagged a finger jokingly in my direction. "But only if there's someone with a valid license in the passenger seat."

I just blinked up at him. "I can't drive," I said.

Dopey let out this big horse laugh. "You can't drive?" He elbowed Sleepy, who was leaning against the side of the truck, his face turned toward the sun. "Hey, Jake, she can't drive!"

"It isn't at all uncommon, Brad," Doc said, "for a native New Yorker to lack a driver's license. Don't you know that New York City boasts the largest mass transit system in North America, serving a population of thirteen point two million people in a four thousand square mile radius fanning out from New York City through Long Island all the way to Connecticut? And that one point seven billion riders take advantage of their extensive fleet of subways, buses, and railroads every year?"

Everybody looked at Doc. Then my mother said, carefully, "I never kept a car in the city."

Andy closed the doors to the back of the Land Rover. "Don't worry, Suze," he said. "We'll get you enrolled in a driver's ed course right away. You can take it and catch up to Brad in no time."

I looked at Dopey. Never in a million years had I ever expected that someone would suggest that I needed to catch up to Brad in any capacity whatsoever.

But I could see I was in for a lot of surprises. The palm trees had only been the beginning. As we drove to the house, which was a good hour away from the airport – and not a quick hour, either, with me wedged in between Sleepy and Dopey, with Doc in the "way back," perched on top of my luggage, still expounding on the glories of the New York City Transportation Authority – I began to realize that things were going to be different – very, very different – than I had anticipated, and certainly different from what I was used to.

And not just because I was living on the opposite side of the continent. Not just because everywhere I looked, I saw things I'd never have seen back in New York: roadside stands advertising artichokes or pomegranates, twelve for a dollar; field after field of grapevines, twisting and twisting around wooden arbors; groves of lemon and avocado trees; lush green vegetation I couldn't even identify. And arcing above it all, a sky so blue, so vast, that the hot air balloon I saw floating through it looked impossibly small – like a button at the bottom of an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

There was the ocean, too, bursting so suddenly into view that at first I didn't recognize it, thinking it was just another field. But then I noticed that this field was sparkling, reflecting the sun, flashing little Morse code SOSs at me. The light was so bright, it was hard to look at without sunglasses. But there it was, the Pacific Ocean... huge, stretching almost as wide as the sky, a living, writhing thing, pushing up against a comma-shaped strip of white beach.

Being from New York, my glimpses of ocean – at least the kind with a beach – had been few and far between. I couldn't help gasping when I saw it. And when I gasped, everybody stopped talking – except for Sleepy, who was, of course, asleep.

"What?" my mother asked, alarmed. "What is it?"

"Nothing," I said. I was embarrassed. Obviously, these people were used to seeing the ocean. They were going to think I was some kind of freak that I was getting so excited about it. "Just the ocean."

"Oh," said my mother. "Yes, isn't it beautiful?"

Dopey went, "Good curl on those waves. Might have to hit the beach before dinner."

"Not," his father said, "until you've finished that term paper."

"Aw, Dad!"

This prompted my mother to launch into a long and detailed account of the school to which I was being sent, the same one Sleepy, Dopey, and Doc attended. The school, named after Junipero Serra, some Spanish guy who came over in the 1700s and forced the Native Americans already living here to practice Christianity instead of their own religion, was actually a huge adobe mission that attracted twenty thousand tourists a year, or something.

I wasn't really listening to my mother. My interest in school has always been pretty much zero. The whole reason I hadn't been able to move out here before Christmas was that there had been no space for me at the Mission School, and I'd been forced to wait until second semester started before something opened up. I hadn't minded – I'd gotten to live with my grandmother for a few months, which hadn't been at all bad. My grandmother, besides being a really excellent criminal attorney, is an awesome cook.

I was sort of still distracted by the ocean, which had disappeared behind some hills. I was craning my neck, hoping for another glimpse, when it hit me. I went, "Wait a minute. When was this school built?"

"The eighteenth century," Doc replied. "The mission system, implemented by the Franciscans under the guidelines of the Catholic Church and the Spanish government, was set up not only to Christianize the Native Americans, but also to train them to become successful tradespeople in the new Spanish society. Originally, the mission served as a – "

"Eighteenth century?" I said, leaning forward. I was wedged between Sleepy – whose head had slumped forward until it was resting on my shoulder, enabling me to tell, just by sniffing, that he used Finesse shampoo – and Dopey. Let me tell you, Gina hadn't mentioned a thing about how much room boys take up, which, when they're both nearly six feet tall, and in the two hundred pound vicinity, is a lot. "Eighteenth century?"

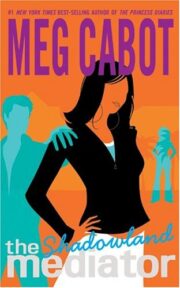

"Shadowland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Shadowland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Shadowland" друзьям в соцсетях.