I guess on the West Coast you aren't supposed to say buh-bye to the principal, or waggle your fingers at him, since when I turned around to face my new classmates, they were all staring at me with their mouths hanging open.

Maybe it was my outfit. I had worn a little bit more black than usual, due to nerves. When in doubt, I always say, wear black. You can never go wrong with black.

Or maybe you can. Because as I looked around at the gaping faces, I didn't see a single black garment in the lot. A lot of white, a few browns, and a heck of a lot of khaki, but no black.

Oops.

Mr. Walden didn't seem to notice my discomfort. He introduced me to the class, and made me tell them where I came from. I told them, and they all stared at me blankly. I began to feel sweat pricking the back of my neck. I have to tell you, sometimes I prefer the company of the undead to the company of my peers. Sixteen-year-olds can be really scary.

But Mr. Walden was a good guy. He only made me stand there a minute, under all those stares, and then he told me to take a seat.

This sounds like a simple thing, right? Just go and take a seat. But you see, there were two seats. One was next to this really pretty tanned girl, with thick, curly honey-blond hair. The other was way in the back, behind a girl with hair so white, and skin so pink, she could only be an albino.

No, I am not kidding. An albino.

Two things influenced my decision. One was that when I saw the seat in the back, I also happened to see that the windows, directly behind that seat, looked out across the school parking lot.

Okay, not such an inspiring view, you might say. But beyond the parking lot was the sea.

I am not kidding. This school, my new school, had a view of the Pacific that was even better than the one in my bedroom since the school was so much closer to the beach. You could actually see the waves from my homeroom's windows. I wanted to sit as close to the window as possible.

The second reason I sat there was simple: I didn't want to take the seat by the tan girl and have the albino girl think I'd done it because I didn't want to sit near anyone as weird looking as she was. Stupid, right? Like she'd even care what I did. But I didn't even hesitate. I saw the sea, I saw the albino, and I went for it.

As soon as I sat down, of course, this girl a few seats away snickered and went, under her breath, but perfectly audibly, "God, sit by the freak, why don't you."

I looked at her. She had perfectly curled hair and perfectly made-up eyes. I said, not talking under my breath at all, "Excuse me, do you have Tourette's?"

Mr. Walden had turned around to write something on the board, but the sound of my voice stopped him. Everybody turned around to look at me, including the girl who'd spoken. She blinked at me, startled. "What?"

"Tourette's Syndrome," I said. "It's a neurological disorder that causes people to say things they don't really mean. Do you have it?"

The girl's cheeks had slowly started turning scarlet. "No."

"Oh," I said. "So you were being purposefully rude."

"I wasn't calling you a freak," the girl said, quickly.

"I'm aware of that," I said. "That's why I'm only going to break one of your fingers after school, instead of all of them."

She spun around real fast to face the front of the classroom. I settled back into my chair. I don't know what everybody started buzzing about after that, but I did see the albino's scalp – which was plainly visible beneath the white of her hair – turn a deep magenta with embarrassment. Mr. Walden had to call everyone to order, and when people ignored him, he slammed his fist down on his desk and told us that if we had so damned much to say, we could say it in a thousand word essay on the battle at Bladensburg during the War of 1812, double-spaced, and due on his desk first thing tomorrow morning.

Oh well. Good thing I wasn't in school to make friends.

CHAPTER 7

And yet I did. Make friends, I mean.

I didn't try to. I didn't even really want to. I mean, I have enough friends back in Brooklyn. I have Gina, the best friend anybody could have. I didn't need any more friends than that.

And I really didn't think anybody here was going to like me – not after having been assigned a thousand word essay because of what happened when I sat down. And especially not after what happened when we were informed that it was time for second period – there was no bell system at the Mission School, we changed class on the hour, and had five minutes to get to where we were going. No sooner had Mr. Walden dismissed us than the albino girl turned around in her seat and asked, her purple eyes glowing furiously behind the tinted lenses of her glasses, "Am I supposed to be grateful to you, or something, for what you said to Debbie?"

"You," I said, standing up, "aren't supposed to be anything, as far as I'm concerned."

She stood up, too. "But that's why you did it, right? Defended the albino? Because you felt sorry for me?"

"I did it," I said, folding my coat over my arm, "because Debbie is a troll."

I saw the corners of her lips twitch. Debbie had swept up her books and practically run for the door the minute Mr. Walden had dismissed us. She and a bunch of other girls, including the pretty tanned one who'd had the empty seat next to her, were whispering amongst themselves and casting me dirty looks over their Ralph Lauren sweater-draped shoulders.

I could tell the albino girl wanted to laugh at my calling Debbie a troll, but she wouldn't let herself. She said, fiercely, "I can fight my own battles, you know. I don't need your help, New York."

I shrugged. "Fine with me, Carmel."

She couldn't help smiling then. When she did, she revealed a mouthful of braces that winked as brightly as the sea outside the window. "It's Cee Cee," she said.

"What's Cee Cee?"

"My name. I'm Cee Cee." She stuck out a milky-white hand, the nails of which were painted a violent orange. "Welcome to the Mission Academy."

At nine o'clock, Mr. Walden had dismissed us. By nine-oh-two, Cee Cee had introduced me to twenty other people, most of whom trotted after me as we moved to our next class, wanting to know what it was like to have lived in New York City.

"Is it really," one horsey-looking girl asked, wistfully, "as... as... " She struggled to think of the word she was looking for. "As... metropolitan as they all say?"

These girls, I probably don't have to add, were not the class lookers. They were not, I saw at once, on speaking terms with the pretty tanned girl and the one whose fingers I'd threatened to break after school, who were the ones so well-turned out in their sweater sets and khaki skirts. Oh, no. The girls who came up to me were a motley bunch, some acned, some overweight, or way, way too skinny. I was horrified to see that one was wearing open-toe shoes with reinforced toe pantyhose. Beige pantyhose, too. And white shoes. In January!

I could see I was going to have my work cut out for me.

Cee Cee appeared to be the leader of their little pack. Editor of the school paper, the Mission News, which she called "more of a literary review than an actual newspaper," Cee Cee had been in earnest when she'd informed me she did not need me to fight her battles for her. She had plenty of ammunition of her own, including a pretty packed arsenal of verbal zingers and an extremely serious work ethic. Practically the first thing she asked me – after she got over being mad at me – was if I'd be interested in writing a piece for her paper.

"Nothing fancy," she said, airily. "Maybe just an essay comparing East Coast and West Coast teen culture. I'm sure you must see a lot of differences between us and your friends back in New York. Whaddaya say? My readers would be plenty interested – especially girls like Kelly and Debbie. Maybe you could slip in something about how on the East Coast being tan is like a faux pas."

Then she laughed, not sounding evil, exactly, but definitely not innocent, either. But that, I soon realized, was Cee Cee, all bright smiles – made brighter by those wicked looking braces – and bouncy good humor. She was as famous, apparently, for her wise-cracking as for her big horselaugh, which sometimes bubbled out of her when she couldn't control it, and rang out with unabashed joy, and was inevitably hushed by the prissy novices who acted as hall monitors, keeping us from bothering the tourists who came to snap pictures of Junipero Serra being fawned over by those poor bronze Indian women.

The Mission Academy was a small one. There were only seventy sophomores. I was thankful that Dopey and I had conflicting schedules, so that the only period we shared in common was lunch. Lunch, by the way, was conducted in the schoolyard, which was to one side of the parking lot, a huge grassy playground overlooking the sea, with seniors slumping on the same benches as second graders, and seagulls converging on anyone foolish enough to toss out a fry. I know because I tried it. Sister Ernestine – the one Adam, who was in my social studies class, it turned out, had called a broad – came up to me and told me never to do it again. As if I hadn't gotten the point the minute fifty giant squawking gulls came swooping down from the sky and surrounded me, the way the pigeons used to in Washington Square Park if you were foolish enough to throw out a bit of pretzel.

Anyway, Sleepy and Doc shared my lunch period, too. That was the only time I saw any of the Ackermans at school. It was interesting to observe them in their native environment. I was pleased to see that I had been correct in my estimation of their characters. Doc hung with a crowd of extremely nerdy-looking kids, most of whom wore glasses and actually balanced their lap top computers on their laps, something I'd never thought was actually done. Dopey hung with the jocks, around whom flocked – the way the seagulls had flocked around me – the pretty tanned girls in our class, including the one I'd eschewed sitting beside. Their conversation seemed to consist of what they'd gotten for Christmas, this being their first day back from winter break, and who'd broken the most limbs skiing in Tahoe.

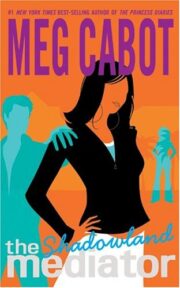

"Shadowland" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Shadowland". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Shadowland" друзьям в соцсетях.