The same day the news was making its way around town, I received two phone calls. One was from Bobby’s mother, who demanded that I come to her house and explain myself. There was some unwritten rule that Mamie Lenehan had a right to poke her nose into everybody’s business, and for some reason, everyone went along with it. The second call was from Father Lynch, and he wanted to see me in the rectory office.

Sadie said she wished that she could be a fly on the wall in the pastor’s office. “I’d love to hear how you’re going to explain this.”

I decided not to explain it. I didn’t go to see Father Lynch, nor did I rush down to Mamie’s to make some sort of confession. I had been out of Minooka for four years, and I was not going to run a gauntlet when I hadn’t done anything wrong. However, in order to be on the safe side, I called my uncle, Father Shea, whose parish was in a small coal town buried deep in the mountains, but who bought his scotch in Scranton.

Raised jointly by my grandmother and Aunt Marie, John Shea was the cigar-smoking, card-playing type of priest, who had worked among the poor of coal country’s mining towns since he had been ordained thirty-five years earlier. In that time, he had shaved his theology down to the two great commandments: Love God and love your neighbor. “Everything else is commentary.” He didn’t preach; he comforted.

I asked him if I was going to go to hell for defying Father Lynch, and he said, “Don’t worry, lass. I’ll give Father Lynch a call and get him to back off. As for Mamie Lenehan, she’ll have enough to think about when she learns Bobby is dating the Mateo girl.”

Michael, who had studied Hinduism, seemed nonplussed by the complexities of the Catholic Church. He left me to sort out the details and went to Judge’s for a beer with Patrick. Before leaving, he said, “It’ll give you an opportunity to bring your father up to speed on why you are marrying me and not Rob, and while you’re at it, see if you can discourage your grandfather from putting me on an IRA hit list.”

After Michael left, I knocked on Grandpa’s bedroom door and asked if I could come in. He was sitting in the shadows smoking his pipe. When my grandmother had died three years earlier, he had started to spend more and more time in his room. In profile, I could see his expansive chest — one of the signs of emphysema — his reward for forty years of working underground.

“So which one will ye be marrying?” he asked.

“Michael, the one with the black hair,” I answered.

Grandpa pointed his pipe at his chest of drawers.

“Go and open Mam’s sewing box.”

I did what he said, but I didn’t know what I was looking for.

“Them silver coins. They washed up on Omey from a Spanish ship. Your Mam’s father give ’em to her before we come to America, saying to sell them if need be. Say what ye will, I be putting food on the table even in the worst of times.” I picked up five silver coins with irregular edges worn down by time and the sea. “Take them. I’ll not be seeing you again.”

Before dismissing me, he spoke at length in Irish, but listening to this ancient tongue spoken by a wheezing man with no teeth, I wasn’t quite getting what he was saying. But my father, who was sitting near the door, later boiled the speech down to one sentence: “Your mother is not always right.”

When I left Grandpa’s room, my mother said her brother had called back. “Father Lynch has agreed to let your uncle handle this situation. But Father Shea wants to talk to you tomorrow afternoon here at the house.” All of this was said in the dispassionate tone she had been using since my return from New York.

“Mom, do you like Michael?” I asked. I believed if she would only give him a chance, she would see what a kind and decent man I was in love with.

“It doesn’t matter what I think. You made that clear when you went to New York. But since you’ve asked, I’ll tell you what I think happened. When you were in England, Rob called it quits on you, so you set your sights on Michael because he’s the one who can make sure you get to stay over there.”

I have never back talked my mother. She didn’t deserve it, and even though what she had said was incredibly hurtful, I was not going to get into an argument with someone who already had too much pain in her life. I took a dish towel out of the drawer and started to dry the dishes. “What if Michael and I had a lengthy engagement? Would that help put your mind at ease?”

Wiping her hands on her apron, she said, “Remember when Suzie Luzowski wanted to marry that Jewish boy? She told her mother that she would stay a Catholic and he would stay Jewish. But the Jewish priest didn’t go for it, saying one was a fish and the other a fowl.” She went back to washing the dishes.

Logic was never my mother’s strong suit. It was part of the reason why she and Dad had such a strained relationship. He had a university education while my mother had left school in the tenth grade to go to work. His was the world of reasoned debate; hers was all emotion based on an innate sense of what was right. But even for my mother, this argument didn’t make sense. Suzie and Seth had gotten married and moved to Philadelphia where he was going to medical school. They had successfully overcome all obstacles, and to the best of my knowledge, were doing well. I decided to leave it alone. Michael was a Protestant, and for someone whose daily life was tied to the Church calendar, it wouldn’t have made a bit of difference anyway.

After telling Michael about my conversation with my mother, he agreed we needed to hold off on a wedding. “I understand why your mother is upset, but I think if she has an opportunity to see the two of us together, she’ll realize how well-suited we are for each other. I’ll just have to stay in Minooka for a few weeks.”

My first reaction was, “Hell no!” But after calming down, I didn’t see any other way to reassure Mom that Michael and I belonged together.

When Father Shea arrived at the house the next morning, I thought he was going to talk to us about laying the foundation for a good Catholic marriage and the importance of bringing the children up in the Church. Instead, he asked Michael about India and the new country of Pakistan. Did Michael think a bloodbath could be avoided between the two countries? As a young priest, my uncle had wanted to be a missionary, and he closely followed international affairs. When Michael took a bathroom break, I hurried after him and told him we needed to get the conversation back on track. Solving Pakistan and India’s problems could wait.

“Father, would you like to go for a walk?” I asked in a pleading voice. Although he was my uncle, we were never allowed to call him anything other than Father Shea.

As soon as we got clear of the house, my uncle asked, “Will you be needing to speak to your Uncle John or Father Shea?”

“Both, I think.”

We were walking up Birney Avenue to the city line when my uncle asked Michael if he attended church regularly. I thought, “Holy crap!”

“Regularly? No, I don’t. When I was in Malta, I occasionally attended chapel. However, there was little opportunity to do so in Germany. Since I’ve been discharged from the service, I haven’t been to church at all.” There was nothing defensive about this statement, and I was wondering how my uncle would react to someone who didn’t apologize for “not keeping holy the Sabbath day.”

“I see,” Father said, clearly not pleased with the answer.

“But what I think you are asking me, Father, is if I honor the Creator and his creation, and I most certainly do and plan to continue doing so through medicine.”

I looked at my uncle to see if that answer satisfied him. He said nothing, and we kept walking. We were nearly to the city line when he finally said, “Michael, I’ve worked among miners for most of my adult life. Their occupation of clawing ore out of a mountain is dehumanizing, so they either turn to the Church or they turn to drink. My goal has been to keep them within the arms of the Holy Mother Church because, without it, they descend into a life of alcoholism and abuse. The Church helped my sister to get through the poverty of her childhood and an abusive stepfather. It has comforted her in the loss of a child. It has given her the strength to live in a household with a mean-spirited old man, an alcoholic husband, and a son with the remarkable ability to find trouble where there was none. You, young man, pose a threat to the very thing that has kept her whole.

“Here’s what I’m going to do. I’ll tell Delia that we spoke at length, and I am convinced your beliefs run deep. I will reassure her that Maggie will continue to attend church.” Father looked at me to see if that would be the case, and I nodded eagerly. “I ask that you delay marrying for at least a year because you come from very different backgrounds. If you agree to a year’s engagement, I think that it will go a long way to putting my sister’s mind at ease. And, Michael, you must understand there is absolutely no divorce in the Catholic Church. Maggie will be your wife in the eyes of the Church until her death.”

After crossing into Scranton, my uncle pointed to Mateo’s Bar and said, “Now, there is a matter of much greater concern — a possible alliance between Bobby Lenehan and Teresa Mateo. Your difficulties pale in comparison.”

Winking at me, my uncle let me know that things would turn out all right. I only hoped that he was right.

Chapter 47

My uncle had barely reached the safety of his mountain parish before a storm came barreling out of the Midwest hitting the Lackawanna Valley with a foot and a half of snow. After digging out our house, Michael took his shovel and went down to Mamie’s where he was bunking out during the Minooka part of our courtship. Bobby had practically begged Michael to stay at his house as a buffer between his mother and him. News of his courtship with Teresa had finally reached his mother, and her reaction had been as expected. A loud, “Hell no!” But Bobby was holding his ground, and Michael’s presence was preventing Mamie from killing him.

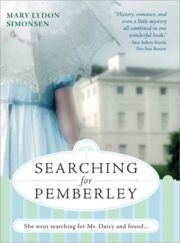

"Searching for Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Searching for Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Searching for Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.