‘You’re quite a philosopher, do you know that?’

He shrugged. ‘I’d have to be, to work here.’

She watched him walk away, then she turned back to the glass case and stared down at the wide-eyed blank stare of the mummy. She couldn’t get the memory of the thin, vulnerable bones of the child she had held so briefly in her arms out of her head. He had been outwardly all that she detested in children. Noisy. Aggressive. Challenging. Somehow out of control, and yet beneath that exterior he had been hurting so badly; pleading for reassurance. And he had come to her.

Slowly she slipped the sketchbook into her bag. One of the sketches would be right for the article. She had done enough. In the corner of the gallery the attendant was talking to a group of women. There were several French students clustered near her now. The school party had long gone.

She thought suddenly of Dan – his quiet pleading, his patience as he tried to explain how much he wanted a child, his anger when she refused even to discuss it. Did he feel this strange need to bring security and love to a small vulnerable human being?

She turned towards the entrance, glancing towards the attendant again and she saw him smile and lift a hand. She hadn’t changed her mind. It wasn’t that easy. Too many strange things had happened in the space of the last hour even to comprehend them all. But maybe, just maybe, it would make her think again.

‘Bye!’ She didn’t realise she had spoken out loud to the mummy in the sterile glass case till she saw someone a few paces away glance up at her, startled. She shrugged apologetically.

The murmured farewell in her ear had been after all, surely, purely in her imagination.

Day Trip

This story is true. Well, more or less. But you must look away, gentle reader, if rude words offend you, for this story can only be told as it happened, with the real dialogue. Asterisks just will not do! It happened one day in autumn.

As Caroline pocketed her car keys and made her way onto the platform her heart sank. It was a small station; often she was the only person to board the train here, especially when she left for London mid-morning, but today the worst happened. There was another passenger waiting as the train drew in – James Campbell, the owner of the huge, immaculate house at the end of the winding lane where Caroline’s cottage stood in its quarter acre of wild garden. There was no time to walk to the other end of the platform. The train was stopping. He was already opening a door, smiling at her with that cold superior smile of his, and bowing slightly to indicate she should enter the carriage ahead of him.

It is hard to incline one’s head graciously while carrying a shoulder bag, a heavy tapestry portmanteau and an A1 black plastic portfolio, especially while dressed in a long flapping skirt which threatened to tangle with her sexy high-heeled boots, but she managed it. With a creditable attempt at dignity she walked to the only set of empty seats and sat down, facing what used in days of old to be called the engine. If he had any tact at all, any discretion, any sense of decency and good manners he would move to the other end of the carriage.

He didn’t. He came and sat down opposite her.

She wasn’t sure quite when her antagonism for this man had begun to develop. The day she moved into the cottage probably. Independence meant an enormous amount to her. This was her first real home and no one, but no one, was going to interfere in the way she decorated it. Or lived her life in it.

She had had an idyllic childhood in her parents’ home. She would be the first to admit that she really had no grounds for complaint at all. No abuse. No deprivation. But she had not at any time been allowed to express her own personality in the decoration of her room. Her nursery, her bedroom, her teenage den – the same room, different incarnations – had all been decorated and furnished to her domineering mother’s taste. Which was attractive. Stylish even. In anyone else’s home she would have admired it. In her own it represented oppression of her individuality and her spirit. Her marriage had been to an interior designer. Perhaps inevitably, given her longing to create her own environment, it had been a disaster. In the house she shared with him she wasn’t even allowed to choose the colour of her own toothbrush. The marriage lasted no time at all.

And then at last she was free. Her mother, her father and even, for heaven’s sake, her ex-husband offered to help her house hunt. When she found the cottage all three felt she had made a mistake. Her mother thought it too twee for words, her father felt it was hopelessly impractical and a bad investment and Phil, her ex, had just one word for the thatch, the honeysuckle, the small leaded windows. Naf.

Undeterred (in fact, if truth were known, greatly encouraged), she embarked on an orgy of do-it-yourself. Decorating, embellishing, improving. Rejecting the share of tasteful furniture due to her as the marital home was divided she settled instead for a dollop of wonderful cash and began to haunt antique shops and car boot sales, country craft fairs and rural art galleries. That was when she discovered she could paint – and, to her astonishment, sell – the wild colourful amazing tangles of flowers which rampaged round her garden.

The first and, to be honest, only dampener on her exuberance outside her own family had been: James Campbell.

‘I trust you intend to do something about those thistles, Mrs Evans.’ His patrician profile had appeared over her gate one day as she was sitting, her face shaded by a broad-brimmed straw hat, sketching the offending plants. He had spotted her and them from his Range Rover and stopped especially to speak to her. No, hello; no, I hope you’re settling in OK; no, welcome to the neighbourhood. Just instant criticism followed by a curt nod before he turned back to his barouche.

Seething, she planned to make a midnight visit to his own regimented acres at dead of night later in the summer. With pockets full of thistle down.

Their relationship from that moment on had steadily deteriorated, his only remarks on the rare occasions they met were patronising and critical and on one occasion were actually conveyed via a formal complaint about her flowering hedges to the Parish Council. Apparently her blackthorn and her holly, her roses and her honeysuckle were scratching the barouche as he drove past.

The train stopped at the next station and several more people boarded. To her relief James Campbell did not look up. He had immediately on sitting down opened his Financial Times. She was spared the horror of having to make polite conversation with him as she produced her own reading – a rather shabby copy of Mrs Leyel’s Herbal Delights. His refusal to further acknowledge her presence was perhaps intended as a slight. If it was it sadly misfired. She was intensely relieved.

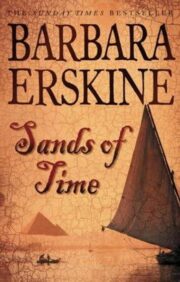

"Sands of Time" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sands of Time". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sands of Time" друзьям в соцсетях.