It obviously had once been the kitchen of the house, or so she thought. She could see the vestiges there. In the inglenook, behind the electric fire, was the bread oven, a salt box, even the iron upright of the sway which had once held a pot over the fire, all invisible beneath an encrustation of centuries-old soot.

She began on the floral wallpaper, the top layer of about six, pulling it off in great flapping wedges. Then, to tackle the Edwardian brown-painted cupboards, the Fifties light fittings and the damp floor, she decided to call in the help of a local builder. She had already had two quotes when Edwin Fosset appeared.

‘I hear you want some work done.’ He looked down at her gravely from gentle grey eyes. He was tall and thin with a kind, lived-in face, attractive in its way, the kind of face she trusted instinctively. In fact, within seconds she felt she had known him all her life. She found herself showing him inside and went to fetch her sketches.

He looked at them critically. ‘It could be a nice room. No problems as far as I can see. I can get started straight away.’ He shivered. ‘It’s chilly in here. Perhaps I should start by opening up these windows and letting in some sunshine!’

That was one of the problems. The room was extraordinarily cold. And depressing. When she stood in it she could feel all her buoyancy and energy draining out of her, as though someone had pulled a plug in the soles of her feet.

She mentioned it to her first guests, her new neighbours, Bob and Julie, who lived up the lane. They admired the living room and the bedroom, came with her into the kitchen while she made coffee and agreed with her that it was too small, then carried their cups with her into the old dining room. ‘This is such a nice room. Potentially,’ she added.

‘Ah,’ Bob said. ‘Potentially.’

‘And what does that mean?’ Julie said, as she stood looking round. ‘Potentially!’ She echoed his voice. ‘It’s a lovely room! Look at the view across the orchards.’

Roz had her eyes fixed on Bob’s face. ‘Don’t tell me. Someone died in here.’ She tried to make it a joke, but it was a thought that kept on occurring to her with depressing regularity, one that had been suggested by several London friends who, on agreeing to visit at some time in the future and promising to bring food parcels as though there were no Sainsbury’s outside the M25 ring, invariably asked with mock caution if there was a ghost and, if so, was it friendly?

Bob shrugged. ‘I’ve never heard of anyone dying in here. But the Grahams, who you bought it from, never used this room. Betty said it was always cold, even in the summer. One of Jim Fosset’s boys is going to work for you, isn’t he? He would know.’

‘Boy?’ Roz giggled. ‘He must be heading towards forty!’

Bob smiled. ‘But this is a village, Roz. People are defined by generations. And the Fossets have been here hundreds of years. The boys’ grandmother ran the village school, and their great-grandmother was cook up at the hall in the old days. And their great-great grandmother was -?’ He hesitated, glancing at his wife.

‘Don’t tell me. She was a witch?’ Roz looked from one to the other expectantly.

Julie shrugged. ‘Not that I’ve heard. I haven’t any idea what she was. I wonder where your builder fits in. He sounds older than the sons, so he might be the cousin who went off and made good. The one who went to university and is reported, by village gossip, to have made a lot of dosh. If that’s true, why is he back here doing work as a jobbing builder?’

‘I got the impression he is a craftsman,’ Roz put in defensively. ‘Perhaps he likes being a builder.’ She had a sudden depressing vision of her newly-acquired friend leaving her amid piles of hammers and dust-sheets to go and attend to his investments. She was intrigued nevertheless.

She found herself thinking often about Edwin’s strong brown hands as he handled his hammer and shovel. His quiet, reserved charm appealed to her more than that of the more extrovert men who had come and gone in her life up to now. She had to admit she found him very attractive. But she was not in the market for a man. What she wanted was a kitchen.

Only two days later Edwin climbed up the stairs to Roz’s study and tapped on the door as she finished a phone call to New York. ‘Can you come down?’

‘What is it?’ She felt a twinge of anxiety.

‘There’s something I want you to see.’ More than that he would not say, and she had to follow the enigmatically silent figure down the twisting staircase into the dining room where he had been digging up the floor to lay a damp-proof course.

‘You haven’t found a body, have you, Edwin?’ She tried to make it a joke. ‘I’ve been waiting for you to unearth something in here.’

He grinned and his face lightened visibly. ‘No, it’s not a body. Look.’

She peered into the earth and dust. ‘What exactly am I supposed to be looking at?’

He sighed. ‘Look. Here.’ He squatted on his haunches and scraped at the loose soil.

She crouched beside him and stared. ‘It looks like old brick.’

‘It is.’ He smiled up at her. ‘Well, tiles, actually. This house is supposed to have medieval foundations, and this is the old floor.’

She knelt to touch the red tiles. ‘I had no idea the house was that old. They are beautiful. Can we expose them and use them, do you think?’ She glanced up. ‘Do you mind my asking? Is it true that you have a degree?’

‘I have.’

‘Am I allowed to ask what in?’

‘History of Architecture.’ He frowned. She had touched on forbidden territory.

She retreated to more neutral ground. ‘So, you would know if we have to report it or anything?’

He relaxed. ‘Yes, I would know.’

Encouraged, she dared to ask the question she had been brooding on. ‘I am going to be nosy. Can I ask why, if you have an architecture degree, you are working on my kitchen?’

He shrugged. ‘It’s a job.’

‘Not a very academic one.’

‘I’m not an academic.’ He picked up the trowel with which he had been digging. ‘Did you mention a cup of tea?’

‘You know I did not.’ She smiled again. ‘But I can take a hint.’

It was half past two in the morning when she was awakened by the sound of shouting. Struggling up from an exhausted sleep, she stared round the room, disorientated. It was silent now, but she was sure the noise hadn’t been part of her dream. Climbing out of bed, she tiptoed to the door and listened. The cottage was completely silent. Outside the open window she heard the call of an owl hunting along the hedge behind the hollyhocks, then all was silent again as the smell of roses drifted up to her.

Pulling open the door as silently as she could, she stepped out onto the landing and crept on bare feet to the top of the stairs. The tiny hairs on her arms, she realised suddenly, were standing on end and she shivered in spite of the warmth of the night.

She could see the moonlight shining from the window of the dining room across the black chasm of the floor and out across the hall towards the staircase. The silence was suddenly oppressive. She took a deep breath and, plucking up courage, forced herself to go down. At the bottom she stopped again, staring into the room as she realised that there was an indistinct figure standing by the fireplace. She stared at it in astonishment.

‘Edwin?’ Her voice came out as a breathless croak.

The figure turned to face her and she was conscious of the pale, drawn face, gentle grey eyes and the worn brown jerkin. Then, as she watched, the figure seemed to fade and disappear. Not Edwin, but someone so like him.

For a moment, total silence still surrounded her, then she became aware of the usual cottage noises. The clock in the hall was ticking, she could hear a tap dripping from the kitchen and suddenly, from the window, came the pure delicate notes of a nightingale.

Abruptly, she sat down on the stairs and buried her face in her arms. She was shaking but it was, she realised, with shock rather than fear. There had been nothing at all frightening about him.

‘I’m dreaming.’ She spoke the words out loud. Taking a deep breath, she stood up and went to the door of the dining room. It was completely empty, the moonlight lying like a silver carpet over the dust and bricks and soil and scatter of tools. She took a few steps into the room, looking round. The figure had been standing in front of the fireplace, staring down into the earth in front of him. She looked down as well. There was nothing there.

When Edwin arrived next morning she was in her office on the telephone. She stood looking down at him as he walked up the path from his van, her concentration only half on what she was saying. Without realising it, she shivered.

When she finally went downstairs, half the floor had been uncovered.

‘Good morning.’ He smiled at her without stopping work.

‘Edwin.’ She hesitated. The face in her dream – if it was a dream – was still haunting her, but how could she admit to dreaming about someone who looked so like him?

‘How long do you think it will take?’ she finished lamely.

‘Not long.’

And with that she had to be content.

Three nights later she was woken up again by the sound of laughter and shouting from downstairs. She stared round in the darkness. There was no moon tonight and she could hear the gentle patter of rain on the roses below her window, filling her room with the sweet scent of wet earth. She lay still for a few seconds, her heart thumping with fear, then slowly and unwillingly she sat up, swinging her legs over the side of the bed.

At the door she paused and frowned. She could smell beer. The sound of talk and laughter grew louder and she could hear the clinking of glasses coming from the dining room.

Creeping downstairs, she tiptoed across the hall and, taking a deep breath, she pushed open the door.

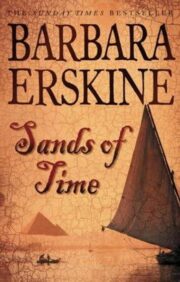

"Sands of Time" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sands of Time". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sands of Time" друзьям в соцсетях.