"What's going on, Officer?" Rob wanted to know, all casual-like. You could tell he, like me, was worried about the whole driving without a license thing. But what kind of police force would set up a roadblock to catch license-less drivers on Thanksgiving? I mean, that was going way above and beyond the call of duty, if you asked me.

"Oh, we got a tip a little while ago," the cop said to Rob. "Regarding some suspicious activity out here. Came out to have a look around." I noticed he hadn't taken out his little ticket book to write me up. Maybe, I thought. Maybe this isn't about me.

Especially considering the floodlight. I could see people traipsing out from and then back into the cornfield. They appeared to be carrying things, toolboxes and stuff.

"You see anything strange?" the police officer asked me. "When you were driving out here from town?"

"No," I said. "No, I didn't see anything."

It was a clear night. . . . Cold, but cloudless. Overhead was a moon, full, or nearly so. You could see pretty far, even though it was only about an hour shy of midnight, by the light of that moon.

Except that there wasn't much to see. Just the big cornfield, stretching out from the side of the road like a dark, rustling sea. Rising above it, off in the distance, was a hill covered thickly in trees. The backwoods. Where my dad used to take us camping, before Douglas got sick, and Mikey decided he liked computers better than baiting fishhooks, and I developed a pretty severe allergy to going to the bathroom out of doors.

People lived in the backwoods … if you wanted to call the conditions they endured there living. If you ask me, anything involving an outhouse is on the same par with camping.

But not everyone who got laid off when the plastics factory closed was as lucky as Rob's mom, who found another job—thanks to me—pretty quickly. Some of them, too proud to accept welfare from the state, had retreated into those woods, and were living in shacks, or worse.

And some of them, my dad once told me, weren't even living there because they didn't have the money to move somewhere with an actual toilet. Some of them lived there because they liked it there.

Apparently not everyone has as fond an attachment as I do to indoor plumbing.

"When you drove through, coming from town," the police officer said, "what time would that have been?"

I told him I thought it had been after eight, but well before nine. He nodded thoughtfully, and wrote down what I said, which was not much, considering I hadn't seen anything. Rob, standing by my mom's car, blew on his gloved hands. It was pretty cold, sitting there with the window rolled down. I felt especially bad for Rob, who was just going to have to climb back on his motorcycle when we were through being questioned and ride behind me all the way into town and then back to his house, without even a chance to get warmed up. Unless of course I invited him into my mom's car. Just for a few minutes. You know. To defrost.

Suddenly I noticed that those police officers, hurrying in and out of that cornfield? Yeah, those weren't toolboxes they were carrying. No, not at all.

Suddenly my palms were sweaty for a whole different reason than before.

Let me just say that in Indiana, they are always finding bodies in cornfields. Cornfields seem to be the preferred dumping ground for victims of foul play by Midwestern killers. That's because until the farmer who owns the field cuts down all the stalks to plant new rows, you can't really see what all is going on in there.

Well, suddenly I had a pretty good idea what was going on in this particular cornfield.

"Who is it?" I asked the policeman, in a high-pitched voice that didn't really sound like my own.

The cop was still busy writing down what I'd said about not having seen anyone. He didn't bother to pretend that he didn't know what I was talking about. Nor did he try to convince me I was wrong.

"Nobody you'd know," he said, without even looking up.

But I had a feeling I did know. Which was why I suddenly undid my seatbelt and got out of the car.

The cop looked up when I did that. He looked more than up. He looked pretty surprised. So did Rob.

"Mastriani," Rob said, in a cautious voice. "What are you doing?"

Instead of replying, I started walking toward the harsh white glow of the floodlight, out in the middle of that cornfield.

"Wait a minute." The cop put away his notebook and pen. "Miss? Um, you can't go over there."

The moon was bright enough that I could see perfectly well even without all the flashing red-and-white lights. I walked rapidly along the side of the road, past clusters of cops and sheriff's deputies. Some of them looked up at me in surprise as I breezed past. The ones who did look up seemed startled, like they'd seen something disturbing. The disturbing thing appeared to be me, striding toward the floodlight in the corn.

"Whoa, little missy." One of the cops detached himself from the group he was in, and grabbed my arm. "Where do you think you're going?"

"I'm going to look," I said. I recognized this police officer, too, only not from the fire at Mastriani's. I recognized this one from Joe Junior's, where I sometimes bussed tables on weekends. He always got a large pie, half sausage and half pepperoni.

"I don't think so," said Half-Sausage, Half-Pepperoni. "We got everything under control. Why don't you get back in your car, like a good little girl, and go on home."

"Because," I said, my breath coming out in white puffs. "I think I might know him."

"Come on now," Half-Sausage, Half-Pepperoni said, in a kindly voice. "There's nothing to see. Nothing to see at all. You go on home like a good girl. Son?" He said this last to Rob, who'd come hurrying up behind him. "This your little girlfriend? You be a good boy, now, and take her on home."

"Yes, sir," Rob said, taking hold of my arm the same way the police officer had. "I'll do that, sir." To me, he hissed, "Are you nuts, Mastriani? Let's go, before they ask to see your license."

Only I wouldn't budge. Being only five feet tall and a hundred pounds, I am not exactly a difficult person to lift up and sling around, as Rob had illustrated a couple of times. But I had gotten pretty mad upon both those occasions, and Rob seemed to remember this, since he didn't try it now. Instead, he followed me with nothing more than a deep sigh as I barreled past the police officers, and toward that white light in the corn.

None of the emergency workers gathered around the body noticed me, at first. The ones on the outskirts of the crime scene hadn't exactly been expecting gawkers this far out from town, and on Thanksgiving night, no less. So it wasn't like they'd been looking out for rubber neckers. There wasn't even any yellow emergency tape up. I breezed past them without any problem. . . .

And then halted so suddenly that Rob, following behind, collided into me. His oof drew the attention of more than a few officers, who looked up from what they were doing, and went, "What the—"

"Miss," a sheriff's deputy said, getting up from the cold hard soil upon which he'd been kneeling. "I'm sorry, miss, but you need to stand back. Marty? Marty, what are you thinking, letting people through here?"

Marty came hurrying up, looking red-faced and ashamed.

"Sorry, Earl," he said, panting. "I didn't see her, she came by so fast. Come on, miss. Let's go—"

But I didn't move. Instead, I pointed.

"I know him," I said, looking down at the body that lay, shirtless, on the frozen ground.

"Jesus." Rob's soft breath was warm on my ear.

"That's my neighbor," I said. "Nate Thompkins."

Marty and Earl exchanged glances.

"He went to get whipped cream," I said. "A couple of hours ago." When I finally tore my gaze from Nate's bruised and broken body, there were tears in my eyes. They felt warm, compared to the freezing air all around us.

I felt one of Rob's hands, heavy and reassuring, on my shoulder.

A second later, the county sheriff, a big man in a red plaid jacket with fleece lining came up to me.

"You're the Mastriani girl," he said. It wasn't really a question. His voice was deep and gruff.

When I nodded, he went, "I thought you didn't have that psychic thing anymore."

"I don't," I said, reaching up to wipe the moisture from my eyes.

"Then how'd you know"—He nodded down at Nate, who was being covered up with a piece of blue plastic—"he was here?"

"I didn't," I said. I explained how Rob and I had come to be there. Also how Dr. Thompkins had been over at my house earlier, looking for his son.

The sheriff listened patiently, then nodded.

"I see," he said. "Well, that's good to know. He wasn't carrying any ID, least that we could find. So now we have an idea who he is. Thank you. You go on home now, and we'll take it from here."

Then the sheriff turned around to supervise what was going on beneath the flood lamp.

Except that I didn't leave. I wanted to, but somehow, I couldn't. Because something was bothering me.

I looked at Marty, the sheriff's deputy, and asked, "How did he die?"

The deputy shot a glance at the sheriff, who was busy talking to somebody on the EMS team.

"Look, miss," Marty said. "You better—"

"Was it from those marks?" I had seen that there'd been some kind of symbol carved into Nate's naked chest.

"Jess." Now Rob had hold of my hand. "Come on. Let's go. These guys have work to do."

"What were those marks, anyway?" I asked Marty. "I couldn't tell."

Marty looked uncomfortable. "Really, miss," he said. "You'd better go."

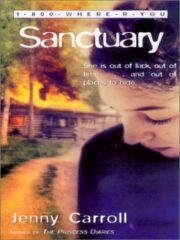

"Sanctuary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sanctuary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sanctuary" друзьям в соцсетях.