"Apple, pumpkin, pecan, and persimmon," my dad said, sounding equally pleased. Good cooks like people who appreciate their food.

No one, however, that I could tell, appreciated Great-aunt Rose.

"Joseph," she said, the minute we reappeared in the dining room. "Who was that colored man?"

It is really embarrassing having a relative like Great-aunt Rose. It isn't even like she is an alcoholic or anything so you can blame her bad behavior on outside forces. She is just plain mean. A couple of times I have considered hauling off and slugging her, but since she is about one hundred years old (okay, seventy-five, big diff) my parents would probably not take too kindly to this. On top of which I have really been trying to curtail my tendency toward violence, thanks to a lawsuit I got slapped with not too long ago for deviating a certain someone's septum.

Though I still think she deserved it.

"African-American, Rose," my mom said. "And he is our neighbor, Dr. Thompkins. Can I get anyone some more wine? Skip, more Coke?"

Skip is Ruth's twin brother. He is supposed to have a crush on me, but he always forgets about it when Claire Lippman is around. That's because all the boys—including my other brother, Douglas—love Claire. It is like she gives off a pheromone or something that girls like Ruth and I don't have. It is somewhat upsetting.

Not, of course, that I want Skip to like me. Because I don't even like Skip. I like someone else.

Someone who was expecting me for Thanksgiving dinner. Only the way things were going—

"What's wrong with saying colored?" Great-aunt Rose wanted to know. "He is colored, isn't he?"

"Can I get you a little more creamed spinach?" Mr. Abramowitz asked Great-aunt Rose. Being a lawyer, he is used to having to be nice to people he doesn't like.

"What'd Dr. Thompkins want?" Skip asked.

"Oh, nothing," my mother said, a little too brightly. "He was just wondering if any of us had seen Nate. Who'd like more mashed potatoes?"

"What's wrong with saying colored?" Great-aunt Rose was mad because no one was paying any attention to her. Though she probably would have changed her tune if I'd paid the kind of attention to her that I wanted to.

"I heard the only reason Dr. Thompkins took the chief surgeon job over at County Medical was because Nate was getting into trouble at their old school." Claire looked around the table as she dropped this little bombshell. Being an actress, Claire enjoys seeing what kind of reactions her little performances generate. Also, since she babysits for all the rich doctor types when she is not attending rehearsals, she knows all the gossip in town. "I heard Nate was in a gang up in Chicago."

"A gang!" Mrs. Lippman looked upset. "Oh, no! That nice boy?"

"Many a nice boy's fallen in with the wrong crowd," Mr. Abramowitz said mildly.

"But Nate Thompkins." Mrs. Lippman, who was big-time involved with the PTA, shook her head. "Why, he's always been so polite when I've seen him at the Stop and Shop."

"Nate may have been involved with some unsavory individuals back in Chicago," my dad said. "But everybody's entitled to a fresh new start. That's one of the ideals this country was founded on, anyway."

"He's probably out there right now," Great-aunt Rose said, with certain relish, "with his little gang friends, getting high on reefer cigarettes."

Mike, Douglas, and I all exchanged glances. It was always amusing to hear Great-aunt Rose use the word "reefer."

My mom apparently didn't find it very amusing, though, since she said, in a stern voice, "Don't be ridiculous, Rose. There are no drugs here. I mean, not in this town."

I didn't think it would be politic to point out to my mom that the weekend before, at the Hello Dolly cast party (Claire, of course, had gotten the part of Dolly), two kids (not Claire, obviously—she doesn't do drugs, as an actress's body, she informed me, is her temple) had been hauled out by EMTs after imbibing in a little too much Ecstasy. It is better in the long run that my mom be shielded from these things.

"Can I be excused?" I asked, instead. "I have to run over to Joanne's house and get those trig notes I was telling you about."

"May I be excused," my mom said. "And no, you may not. It's Thanksgiving, Jessica. You have three whole days off. You can pick up the notes tomorrow."

"You know somebody graffitied the overpass last week," Mrs. Lippman informed everyone. "You can't even tell what it says. I never thought of it before now, but supposing it's one of those … what do they call them, again? I saw it on Sixty Minutes. Oh, yes. A gang tag. I mean, I'm sure it's not. But what if it is?"

"I can't get the notes tomorrow," I said. "Joanne's going to her grandma's tomorrow. Tonight's the only time I can get them."

"Hush," my mom said.

"Reefer today," Great-aunt Rose said, shaking her head. "Heroin tomorrow."

"You don't know anybody named Joanne," Douglas leaned over to whisper in my ear.

"Mom," I said, ignoring Douglas. Which was kind of mean, on account of it had taken a lot for him even to come down to dinner at all. Douglas is not what you'd call the most sociable guy. In fact, antisocial is more the word for it, really. But he's gotten a little better since he started a job at a local comic book store. Well, better for him, anyway.

"Come on, Mom," I said. "I'll be back in less than an hour." This was a total lie, but I was hoping that she'd be so busy with her guests and everything, she wouldn't even notice I wasn't home yet.

"Jessica," my dad said, signaling for me to help him start gathering people's plates. "You'll miss pie."

"Save a piece of each for me," I said, reaching out to grab the plates nearest me, then following him into the kitchen. "Please?"

My dad, after rolling his eyes at me a little, finally tilted his head toward the driveway. So I knew it was okay.

"Take Ruth with you," my dad said, as I was pulling my coat down from its hook by the garage door.

"Aw, Dad," I said.

"You have a learner's permit," my dad said. "Not a license. You may not get behind the wheel without a licensed driver in the passenger seat."

"Dad." I thought my head was going to explode. "It's Thanksgiving. There is no one out on the streets. Even the cops are at home."

"It's supposed to snow," he said.

"The forecast said tomorrow, not tonight." I tried to look my most dependable. "I will call you as soon as I get there, and then again, right before I leave. I swear."

"Well, Joe." Mr. Lippman walked into the kitchen. "May I extend my compliments to the chef? That was the best Thanksgiving dinner I've had in ages."

My dad looked pleased. "Really, Burt? Well, thank you. Thank you so much."

"Dad," I said, standing by the heart-shaped key peg by the garage door.

My dad barely looked at me. "Take your mother's car," he said to me. Then, to Mr. Lippman, he went, "You didn't think the mashed potatoes were a little too garlicky?"

Victorious, I snatched my mom's car keys—on a Girl Scout whistle key chain, in case she got attacked in the parking lot at Wal-Mart; no one had ever gotten attacked there before, but you never knew. Besides, everybody had gotten paranoid since Mastriani's burnt down, even though they'd caught the perps—and I bolted.

Free at last, I thought, as I climbed behind the wheel of her Volkswagen Rabbit. Free at last. Thank God almighty, I am free at last.

Which is an actual historical quote from a famous person, and probably didn't really apply to the current situation. But believe me, if you'd been cooped up all evening with Great-aunt Rose, you'd have thought it, too.

About the license thing. Yeah, that was kind of funny, actually. I was virtually the only junior at Ernie Pyle High who didn't have a driver's license. It wasn't because I wasn't old enough, either. I just couldn't seem to pass the exam. And not because I can't drive. It's just this whole, you know, speed limit thing. Something happens to me when I get behind the wheel of a car. I don't know what it is. I just need—I mean really need—to go fast. It must be like a hormonal thing, like Mike and Claire Lippman, because I fully can't help it.

So really, my parents have no business letting me use the car. I mean, if I got into a wreck, no way was their insurance going to cover the damages.

But the thing was, I wasn't going to get into a wreck. Because except for the lead foot thing, I'm a good driver. A really good driver.

Too bad I suck at pretty much everything else.

My mother's car is a Rabbit. It doesn't have nearly the power of my dad's Volvo, but it's got punch. Plus, with me being so short, it's a little easier to maneuver. I backed out of the driveway—piece of cake, even in the dark—and pulled out onto empty Lumbley Lane. Across the street, all the lights in the Hoadley place—I mean, the Thompkins place—were blazing. I looked up, at the windows directly across the street from my bedroom dormers. Those, I knew, from having seen her in them, were Tasha Thompkins's bedroom windows. The Thompkinses, who had grandparents visiting—I knew because they'd turned down my mom and dad's invitation to Thanksgiving dinner on account of their already having their own guests—had eaten earlier than we had, if Nate had been sent out two hours ago for whipped cream. Tasha, I could see, was upstairs in her room already. I wondered what she was doing. I hoped not homework. But Tasha sort of seemed like the homework-after-Thanksgiving-dinner kind of girl.

Unlike me. I was the sneak-out-to-meet-her-boyfriend-after-Thanksgiving-dinner kind of girl.

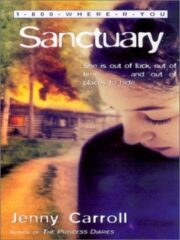

"Sanctuary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sanctuary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sanctuary" друзьям в соцсетях.