"Wait a minute," Rob said. "Dr. Krantz? When did you talk to Krantz? Was that him just now?"

"I'm sorry, Rob," I said. I could see Mickey and Claire looking at me with growing concern. I knew I'd have to pull myself together soon, or Mike would go get my mother. "Look, I've got to go—"

But Rob, as usual, was already taking charge of the situation.

"What's the connection?" Rob wanted to know. "What does Krantz say?"

All I wanted to do was hang up the phone, go upstairs to my room, and climb into bed. Yes, that was it. That was what I needed to do. Go back to sleep, and wake up again tomorrow, so that all of this would just seem like a bad dream.

"Mastriani!" Rob yelled in my ear. "What's the connection?"

"It's the symbol, okay?" I couldn't believe he was yelling at me. I mean, I wasn't the one who'd shot a cop, or anything. "The one that was on Nate's chest. It's the same thing that was spray-painted onto the headstones at the synagogue."

"What does it look like?" Rob wanted to know. "This symbol?"

Look, Rob is my soul mate and all, but that doesn't mean that there aren't times when I don't feel like hauling off and decking him. Now was one of those times.

"Jeez, Rob," I said. "You were there in that cornfield with me, remember?" This caused a pointed look to be exchanged between my brother and his girlfriend, but I ignored them. "Didn't you notice what Nate had on his chest?"

Rob's voice was strangely quiet. "No, not really," he said. "I didn't … I didn't actually look. That kind of thing … well, I don't really do too well, you know, at the sight of …"

Blood. He didn't say it, but then, he didn't have to. All my annoyance with him dissipated. Just like that.

Well, love will do that to you.

"It was this squiggly line," I explained. "With an arrow coming out of one end."

"An arrow," Rob echoed.

"Yeah," I said. "An arrow."

"An M? The squiggly line. Was it shaped like a M, only on its side?"

"I don't know," I said. "I guess so. Look, Rob, I don't feel so good. I gotta go—"

Then Rob said a strange thing. Something that got my attention right away, even though I was feeling so lousy, like I was going to pass out, practically.

He said, "It's not an arrow."

I had been about to press the Talk button and hang up the phone. When he said that, however, I stopped myself. "What do you mean, it's not an arrow?"

"Jess," he said. The fact that he used my first name made me realize the situation was far from normal. "I think I might know who these people are. The people who are doing this stuff."

I didn't even hesitate. It was like all of a sudden, the blood that had seemed frozen in my veins was flowing again.

"I'll meet you at the Stop and Shop," I said. "Come pick me up."

"Mastriani—"

"Just be there," I said, and hung up. Then I threw down the phone, got up, and started for the stairs.

"Jess, wait," Michael called. "Where are you going?"

"Out," I called back. "Tell Mom I'll be home soon."

And then, after struggling into my hat and coat, I was tearing off down the street. I couldn't help noticing as I jogged that while our own driveway was still full of snow, the Thompkinses' driveway had been shoveled so clean, you could practically have played basketball on it. All the snow that had been shoveled away was piled along the curb, as neatly as if a plow had pushed it there.

But it hadn't been the work of a plow. Oh, no. It was the work of a person. Namely, my brother Douglas.

Love. It makes people do the craziest things.

C H A P T E R

10

Chick—owner and proprietor of Chick's Bar and Motorcycle Club—looked down at the drawing I had made and went, "Oh, sure. The True Americans."

I looked at the squiggle. It was kind of hard to see in the dark gloom of the bar.

"Are you sure?" I asked. "I mean … you really know what this is?"

"Oh, yeah." Chick was eating a meatball sandwich he'd made for himself back in the kitchen. He'd offered one to each of us, as well, but we'd declined the invitation. Our loss, Chick had said.

Now a large piece of meatball escaped from between the buns Chick clutched in one of his enormous hands, and it dropped down onto the drawing I'd made. Chick brushed it away with a set of hairy knuckles.

"Yeah," he said, squinting down at the drawing in the blue-and-red neon light from the Pabst Blue Ribbon sign behind the bar. "Yeah, that's it, all right. They all got it tattooed right here." He indicated the webbing between his thumb and index finger. "Only you got it sideways, or something."

He turned the drawing so that instead of looking like

"There," Chick said. There was sauce in his goatee, but he didn't seem to know it … or care, anyway. "Yeah. That's how it's supposed to look. See? Like a snake?"

"Don't tread on me," Rob said.

"Don't what?" I asked.

It was weird to be sitting in a bar with Rob. Well, it would have been weird to have been sitting in a bar with anyone, seeing as how I am only sixteen and not actually allowed in bars. But it was particularly weird to be in this bar, and with Rob. It was the same bar Rob had taken me to that first time he'd given me a ride home from detention, nearly a year earlier, back when he hadn't realized I was jailbait. We hadn't imbibed or anything—just burgers and Cokes—but it had been one of the best nights of my entire life.

That was because I had always wanted to go to Chick's, a biker bar I had been passing every year since I was a little kid, whenever I went with my dad to the dump to get rid of our Christmas tree. Far outside of the city limits, Chick's held mystery for a Townie like me—though Ruth, and most of the rest of the other people I knew, called it a Grit bar, filled as it was with bikers and truckers.

That night, however—even though it was a Saturday—the place was pretty much devoid of customers. That was on account of all the snow. It was no joke, trying to ride a motorcycle through a foot and a half of fresh powder. Rob thankfully hadn't even tried it, and had come to get me instead in his mother's pickup.

But he had been one of the few to brave the mostly unplowed back countryroads. With the exception of Rob and me, Chick's was empty, of both clientele and employees. Neither the bartender nor the fry cook had made it in. Chick hadn't been too happy about having to make his own sandwich. But mostly, if you ask me, because he was so huge, he didn't fit too easily in the small galley kitchen out back.

"Don't tread on me," Rob repeated, for my benefit. "Remember? That was printed on one of the first American flags, along with a coiled snake." He held up my drawing, but tilted it the way Chick had. "That thing on the end isn't an arrow. It's the snake's head. See?"

All I saw was still just a squiggly line with an arrow coming out of it. But I went, "Oh, yeah," so I wouldn't seem too stupid.

"So, these True Americans," I said. "What are they? A motorcycle gang, like the Hell's Angels, or something?"

"Hell, no!" Chick exploded, spraying bits of meatball and bread around. "Ain't a one of 'em could ride his way out of a paper bag!"

"They're a militia group, Mastriani," Rob explained, showing a bit more patience than his friend and mentor, Chick. "Run by a guy who grew up around here … Jim Henderson."

"Oh," I said. I was trying to appear worldly and sophisticated and all, since I was in a bar. But it was kind of hard. Especially when I didn't understand half of what anybody was saying. Finally, I gave up.

"Okay," I said, resting my elbows on the sticky, heavily graffitied bar. "What's a militia group?"

Chick rolled his surprisingly pretty blue eyes. They were hard to notice, being mostly hidden from view by a pair of straggly gray eyebrows.

"You know," he said. "One of those survivalist outfits, live way out in the backwoods. Won't pay their taxes, but that don't seem to stop 'em from feeling like they got a right to steal all the water and electricity they can."

"Why won't they pay their taxes?" I asked.

"Because Jim Henderson doesn't approve of the way the government spends his hard-earned money," Rob said. "He doesn't want his taxes going to things like education and welfare … unless the right people are the ones receiving the education and welfare."

"The right people?" I looked from Rob to Chick questioningly. "And who are the right people?"

Chick shrugged his broad, leather-jacketed shoulders. "You know. Your basic blond, blue-eyed, Aryan types."

"But …" I fingered the smooth letters of a woman's name—BETTY—that had been carved into the bar beneath my arms. "But the true Americans are the Native Americans, right? I mean, they aren't blond."

"It ain't no use," Chick said, with his mouth full, "arguin' semantics with Jim Henderson. To him, the only true Americans're the ones that climbed down offa the Mayflower … white Christians. And you ain't gonna tell 'im differently. Not if you don't want a twelve gauge up your hooha."

I raised my eyebrows at this. I wasn't sure what a hooha was. I was pretty sure I didn't want to know.

"Oh," I said. "So they killed Nate …"

"… because he was black," Rob finished for me.

"And they burned down the synagogue …"

"… because it's not Christian," Rob said.

"So the only true Americans, according to Jim Henderson," I said, "are people who are exactly like … Jim Henderson."

Chick finished up his last bite of meatball sandwich. "Give the girl a prize," he said, with a grin, revealing large chunks of meat and bread trapped between his teeth.

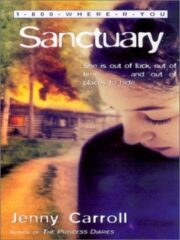

"Sanctuary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sanctuary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sanctuary" друзьям в соцсетях.