"Was that Tasha Thompkins I just saw leaving here?" Ruth wanted to know.

"Yes," I said. "That was her all right."

"I didn't know you two were so friendly," Ruth said to me, as she began to unwind her scarf from her neck. "That was nice of you to ask her over."

"I didn't," I said.

Ruth looked confused. "Then what was she doing here?"

"Ask him," I said, tilting my head in Douglas's direction.

He ducked back over his computer, but I could still see the tips of his ears reddening.

"What's a guy have to do," he wanted to know, "to get some privacy around here?"

C H A P T E R

8

When I woke up the next morning, I knew where Seth Blumenthal was.

And where Seth Blumenthal was wasn't good. It wasn't good at all.

Having the psychic power to find anyone, anyone at all, isn't an easy thing to live with. I mean, look at how, just by seeing his picture on the wall of Mrs. Wilkins's bedroom, I now knew this thing about Rob's dad. I would have traded anything in the world not to have been in possession of that little piece of information, let me tell you.

Just as I would have traded anything in the world not to have to do what I knew I had to next.

No big deal, right? Just pick up the phone and dial 911, right?

Not. So not.

Normally when I am contacted about a missing kid, it goes like this: I make sure, before I call anyone, that the kid really does want to be found. This is on account of how once I found a kid who was way better off missing than with his custodial parent, who was a bonafide creep. Ever since then, I have really gone out of my way to make sure the kids I find aren't better off missing.

But in Seth's case, there was no question. No question at all.

But I couldn't simply pick up the phone, dial 911, and go, "Oh, yeah, hi, by the way, you'll find Seth Blumenthal on blankity-blank street; hurry up and get him, his mom's missing him a lot," and hang up, click.

Because ever since this whole psychic thing started, and the U.S. government began expressing its great desire to put me on the payroll, I've been having to pretend like I don't have my powers anymore. So how would it look if I called 911 from my bedroom phone and went, "Oh, yeah, Seth Blumenthal? Here's where to find him."

Not cool. Not cool at all.

So I had to get up and go find a pay phone somewhere so that at least I could give the semblance of a denial the next time Cyrus Krantz accuses me of lying about my "specially abled-ness."

But let me tell you, if there'd ever been a day I considered giving up on the whole subterfuge thing, it was this one. That's because when I stumbled out of my bed, heading for the space heater I always turned off before I went to sleep, only to wake with ice chips practically formed in my nostrils, I happened to look out the window, and noticed that Lumbley Lane was completely carpeted in white.

That's right. It had started snowing around four in the afternoon the day before, and apparently, it had not stopped. There had to be a foot and a half at least of fluffy white stuff already on the ground, and more was falling.

"Great," I muttered, as I hastily donned an extra pair of socks and all the flannel I could find. "Just great."

With that much snow, there'd naturally be a hush over everything outside. But there seemed to be an equal silence inside the house. As I came down the stairs, I noticed that neither Douglas nor Mikey's rooms were occupied. And when I got to the kitchen, the only person sitting there, unfortunately, was Great-aunt Rose.

"I hope you don't think you're going to go out looking like that," she said, over the steaming cup of coffee she was holding. "Why, you look like you just pulled some old clothes on over your pajamas."

Since this was exactly what I had done, I was not exactly ruffled by this statement.

"I'm just going to the convenience store," I said. I went over to the mudroom and started tugging on some boots. "I'll be right back. You want anything?"

"The convenience store?" Great-aunt Rose looked shocked. "You have a refrigerator stocked with every kind of food imaginable, and you still can't find something to eat? What could you possibly need from the convenience store?"

"Tampons," I said, to shut her up.

It didn't work, though. She just started in about toxic shock syndrome. She'd seen an episode of Oprah about it once.

"And by the time they got to her," Great-aunt Rose was saying, as I stomped around, looking for a pair of mittens, "her uterus had fallen out!"

I knew someone whose uterus I wished would fall out. I didn't say so, though. I pulled a ski cap over my bed-head hair and went, "I'll be right back. Where is everybody, anyway?"

"Your brother Douglas," Great-aunt Rose said, "left for that ridiculous job of his in that comic book store. What your parents can be thinking, allowing him to fritter away his time in a dead-end job like that, I can't imagine. He ought to be in school. And don't tell me he's sick. There isn't a single thing wrong with Douglas except that your parents are coddling him half to death. What that boy needs isn't pills. It's a swift kick in the patootie."

I could see why none of Great-aunt Rose's own kids ever invited her over anymore for the holidays. She was a real joy to have around.

"What about my mom and dad?" I asked. "Where are they?"

"Your father went to one of those restaurants of his," Great-aunt Rose said, in tones of great disapproval. Restauranting was probably, in her opinion, another example of time frittered away. "And your other brother went with your mom."

"Oh, yeah?" I pulled on the biggest, heaviest coat I could find. It was my dad's old ski parka. It was about ten sizes too big for me, but it was warm. Who cared if I looked like Nanook of the North? I certainly wasn't trying to impress the guys at the Stop and Shop. "Where'd they go?"

"To the fire," Great-aunt Rose said, and turned back to the newspaper that was spread out in front of her. LOCAL RESIDENT FOUND DEAD, screamed the headline. FOUL PLAY SUSPECTED. Uh, no duh.

I thought Great-aunt Rose had finally gone round the bend. You know, Alzheimer's. Because the fire that had burned down the restaurant had been nearly three months ago.

"You mean Mastriani's?" I asked. "They went to the job site?" It didn't make much sense that they'd go there, especially on a day like today. The contractors who were rebuilding the restaurant had knocked off for the winter. They said they'd finish the place in the spring, when the ground wasn't so hard.

So what were my mom and Michael doing at an empty lot?

"Not that fire," Great-aunt Rose said, disparagingly. "The new one. The one at that Jewish church."

Now Great-aunt Rose had my full attention. I stared at her dumbfounded. "There's a fire at the synagogue?"

"Synagogue," Great-aunt Rose said. "That's what they call it. Whatever. Looks like a church to me."

"There's a fire at the synagogue?" I repeated, more loudly.

Great-aunt Rose gave me an irritated look. "That's what I said, didn't I? And there's no need to shout, Jessica. I may be old, but I'm not—"

Deaf, is what she probably said. I wouldn't know, since I booked out of there before she could finish her sentence.

A fire at the synagogue. This was not a good thing. I mean, not that I go to temple, not being Jewish.

Still, Ruth and her family go to temple. They go to temple a lot.

And if the fire was big enough that my mom and Mikey had felt compelled to go …

Oh, yes. The fire was big enough. I saw the dark plume of smoke in the air before I even got to the end of Lumbley Lane. This was not good.

I slogged through the snow, heading for the Stop and Shop, which was fortunately in the same direction as the synagogue. They have plows in my town, but it takes forever for them to get around to the residential streets. They do all the roads around the hospital and courthouse first, then the residential areas … if they don't have to go back and do the important roads again, which, in a storm like this, they'd need to. They never bothered with rural routes at all. A big storm tended to guarantee that everyone who lived outside the city limits was snowed in for days. Which was good for kids—no school—but not so good for adults, who had to get to work. Lumbley Lane had not been plowed. Only our driveway had been shoveled. Mr. Abramowitz, the champion shoveler in the neighborhood, had barely made a dent in his driveway. . . . Only enough had been shoveled so that he could get the car out, undoubtedly so that he and his family could head over to the synagogue and see what they could do to help, the way my mom and Mikey had. In a small town, people tend to pitch in. This can be a good thing, but it can also be a bad thing. For instance, people are also eager to pitch in with the latest gossip. Which—case in point, Nate Thompkins—was not always so helpful.

By the time I got to the Stop and Shop, which was only a few streets away from my house, I was panting from the exertion of wading through so much snow. Plus my face felt frozen on account of the wind whipping into it, despite my dad's voluminous hood.

Still, I couldn't go inside to warm up. I had a call to make on the pay phone over by the air hose.

"Yeah," I said, when the emergency operator picked up. "Can you please let the police know that the kid they've been looking for, Seth Blumenthal, is at Five-sixty Rural Route One, in the second trailer to the right of the Mr. Shaky's sign?"

The operator, stunned, went, "What?"

"Look," I said. This was really just my luck. You know, getting a brain-dead emergency services operator, on top of a freaking snowstorm. "Get a pen and write it down." I repeated my message one more time. "Got it?"

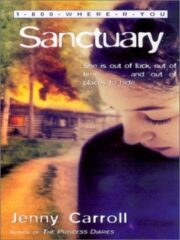

"Sanctuary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sanctuary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sanctuary" друзьям в соцсетях.