I looked down at myself in surprise. "Oh," I said. "School."

"School?" Douglas seemed shocked. "Since when have you ever bothered dressing up for school?"

"I'm turning over a new leaf," I informed him. "No more jeans, no more T-shirts, no more fighting, no more detention."

"Interesting corollary," Douglas said. "Equating jeans with fighting and detention. But I'll bite. Did it work?"

"Not exactly," I said, and told him about my day, leaving out the part about what Heather had said concerning him.

When I was through, Doug whistled, low and long.

"So they're blaming you," he said. "Even though you couldn't possibly have known anything about it?"

"Hey," I said with a shrug. "Amber was in with the popular crowd, and popular kids are not popular for their ability to objectively reason. Just for their looks, mainly. Or maybe their ability to suck up."

"Jeez," Douglas said. "What are you going to do?"

"What can I do?" I asked with a shrug. "I mean, she's dead."

"Couldn't you—I don't know. Couldn't you summon up a picture of her killer? Like in your mind's eye? Like if you really concentrated?"

"Sorry," I said in a flat voice. "It doesn't work like that."

Unfortunately. My psychic ability does not extend itself toward anything other than addresses. Seriously. Show me a picture of anyone, and that night, I'll dream up the person's most current location. But precognitive indications of the lottery numbers? No. Visions of plane crashes, or impending national doom? Nothing. All I can do is locate missing people. And I can only do that in my sleep.

Well, most of the time, anyway. There'd been a strange incident over the summer when I'd managed to summon up someone's location just by hugging his pillow. . . .

But that, I remained convinced, had been a fluke.

"Oh," Douglas said suddenly, leaning over to pull something out from beneath his bed. "By the way, I was in charge of collecting the Abramowitzes' mail while they were away, and I took the liberty of relieving them of this." He presented me with a large brown envelope that had been addressed to Ruth. "From your friend at 1-800-WHERE-R-YOU, I believe?"

I took the envelope and opened it. Inside—as there was every week, mailed to Ruth, since I suspected the Feds were going through my mail, just waiting for something like this to prove I'd been lying to them when I'd said I was no longer psychic—was a note from my operative at the missing children's organization—Rosemary—and a photo of a kid she had determined was really and truly missing . . . not a runaway, who might be missing by choice, or a kid who'd been stolen by his noncustodial parent, who might be better off where he was. But an actual, genuinely missing kid.

I looked at the picture—of a little Asian girl, with buckteeth and butterfly hair clips—and sighed. Amber Mackey, who'd sat in front of me in homeroom every day for six years, might be dead. But for the rest of us, life goes on.

Yeah. Try telling that to Amber's parents.

C H A P T E R

4

When I woke up the next morning, I knew two things: One, that Courtney Hwang was living on Baker Street in San Francisco. And two, that I was going to take the bus to school that day.

Don't ask me what one had to do with the other. My guess would be a big fat nothing.

But if I took the bus to school, I'd have an opportunity that I wouldn't if I let Ruth drive me to school in her Cabriolet: I'd be able to talk to Claire Lippman, and find out what she knew about the activities at the quarry just before Amber went missing.

I called Ruth first. My call to Rosemary would have to wait until I found a phone that no one could connect me to, if 1-800-WHERE-R-YOU happened to trace the call. Which they did every call they got, actually.

"You want to take the bus," Ruth repeated, incredulously.

"It's nothing against the Cabriolet," I assured her. "It's just that I want to have a word with Claire."

"You want to take the bus," Ruth said again.

"Seriously, Ruth," I said. "It's just a one-time thing. I just want to ask Claire a few questions about what was up at the quarry the night Amber disappeared."

"Fine," Ruth said. "Take the bus. See if I care. What have you got on?"

"What?"

"On your body. What are you wearing on your body?"

I looked down at myself. "Olive khaki mini, beige crocheted tank with matching three-quarter-sleeve cardigan, and beige espadrilles."

"The platforms?"

"Yes."

"Good," Ruth said, and hung up.

Fashion is hard. I don't know how those popular girls do it. At least my hair, being extremely short and sort of spiky, didn't have to be blow-dried and styled. That would just about kill me, I think.

Claire was sitting on the stoop of the house where the bus picked up the kids in our neighborhood. I live in the kind of neighborhood where people don't mind if you do this. Sit on their stoop, I mean, while waiting for the bus.

Claire was eating an apple and reading what looked to be a script. Claire, a senior, was the reigning leading lady of Ernie Pyle High's drama club. In the bright morning sunlight, her red bob shined. She had definitely blow-dried and styled just minutes before.

Ignoring all the freshmen geeks and car-less rejects that were gathered on the sidewalk, I said, "Hi, Claire."

She looked up, squinting in the sun. Then she swallowed what she'd been chewing and said, "Oh, hi, there, Jess. What are you doing here?"

"Oh, nothing," I said, sitting down on the step beneath the one she'd appropriated. "Ruth had to leave early, is all." I prayed Ruth wouldn't drive by as I said this, and that if she did, she wouldn't tootle the horn, as she was prone to when we passed what we've always considered the rejects at the bus stop.

"Huh," Claire said. She glanced admiringly down at my bare leg. "You've got a great tan. How'd you get it?"

Claire Lippman has always been obsessed with tanning. It was because of this obsession, actually, that my brother Mike had become obsessed with her. She spent almost every waking hour of the summer months on the roof of her house, sunbathing … except when she could get someone to drive her to the quarries. Swimming in the quarries was, of course, against the law, which was why everyone did it, Claire Lippman more than anyone. Though, as a redhead, her hobby must have been a particularly frustrating one for her, since it took almost a whole summer of exposure to turn her skin even the slightest shade darker. Sitting beside her, I felt a little like Pocahontas. Pocahontas hanging out with The Little Mermaid.

"I worked as a camp counselor," I explained to her. "And then Ruth and I spent two weeks at the dunes, up at Lake Michigan."

"You're lucky," Claire said wistfully. "I've just been stuck at the stupid quarries all summer."

Pleased by this smooth entré into the subject I'd been longing to discuss with her, I started to say, "Hey, yeah, that's right. You must have been there, then, the day Amber Mackey went missing—"

That's what I started to say, anyway. I didn't get a chance to finish, however. That was because, to my utter disbelief, a red Trans Am pulled up to the bus stop, and Ruth's twin brother Skip leaned out of the T-top to call, "Jess! Hey, Jess! What are you doing here? D’ju and Ruth have another fight?"

All the geeks—the backpack patrol, Ruth and I called them, because of their enormous, well, backpacks—turned to look at me. There is nothing, let me tell you, more humiliating than being stared at by a bunch of fourteen-year-old boys.

I had no choice but to call back to Skip, "No, Ruth and I did not get into a fight. I just felt like riding the bus today."

Really, in the history of the bus stop, had anyone ever uttered anything as lame as that?

"Don't be an idiot," Skip said. "Get in the car. I'll drive you."

All the nerds, who'd been staring at Skip while he spoke, turned their heads to look expectantly at me.

"Um," I said, feeling my cheeks heating up and thankful my tan hid my blush. "No, thanks, Skip. Claire and I are talking."

"Claire can come, too." Skip ducked back inside the car, leaned over, and threw open the passenger door. "Come on."

Claire was already gathering up her books.

"Great!" she squealed. "Thanks!"

I followed more reluctantly. This was so not what I'd had in mind.

"Come on, Claire," Skip was saying as I approached the car. "You can get in back—"

I saw Claire, who was a willowy five-foot-nine if she was an inch, hesitate while looking into the cramped recesses of Skip's backseat. With a sigh, I said, "I'll get in back."

When I was wedged into the dark confines of the Trans Am's rear seat, Claire threw the passenger seat back and climbed in.

"This is so sweet of you, Skip," she said, checking out her reflection in his rearview mirror. "Thanks a lot. The bus is okay, and all, but, you know. This is much better."

"Oh," Skip said, fastening his seatbelt. "I know. You all right back there?" he asked me.

"Fine," I said. I had, I knew, to turn the conversation back to the subject of the quarries. But how?

"Great." Skip threw the car into gear and we were off, leaving the geeks in our dust. Actually, that part I sort of enjoyed.

"So," Skip said, "how are you ladies this morning?"

See? This is the problem with Skip. He says things like "So, how are you ladies this morning?" How are you supposed to take a guy who says things like that seriously? Skip's not ugly, or anything—he looks a lot like Ruth, actually: a chubby blond in glasses. Only, of course, Skip doesn't have breasts.

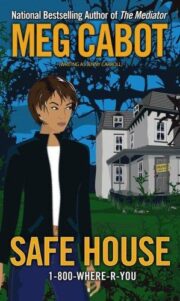

"Safe House" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Safe House". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Safe House" друзьям в соцсетях.