Mark opened his own driver's side door, reached inside his car, and pulled out a duffel bag. Then he closed the door again and locked it. At our glances, which I suppose he perceived as curious—though in my case, it was merely glazed—he went, "Football practice," then shouldered the bag, and headed off in the direction of the gym.

"Jess," Ruth said when he was out of earshot. "Did I hear that correctly? Did Mark Leskowski just ask you out?"

"Yeah," I said.

"So that's how many people who've asked you out today? Two?"

"Yeah," I said, climbing into the passenger seat after she unlocked it from the inside.

"Jeez, Jess," she said. "That's like a record, or something. Why aren't you happier?"

"Because," I said, "one of the guys who asked me out today was, up until recently, a suspect in his own girlfriend's murder, and the other one is your brother."

Ruth went, "Yeah, but isn't Mark off the hook now, on account of what happened to Heather?"

"I guess so," I said. "But...."

"But what?" Ruth asked.

"But . . . Ruth, Tisha says they all knew about that house. Almost like . . . they're the ones who hang out there."

"Meaning?"

"Meaning it must have been one of them."

"One of who?"

"The in crowd," I said, gesturing toward the football field, where we could see the cheerleaders and some of the players already out there, practicing.

"Not necessarily," Ruth said. "I mean, Tisha knew about the house. She didn't say she'd ever been in there partying, did she?"

"Well," I said. "No. Not exactly. But—"

"I mean, come on. Don't you think those guys could find a nicer place to party? Like Mark Leskowski's parents' rec room, for instance? I mean, I hear the Leskowskis have an indoor/outdoor pool."

"Maybe Mr. and Mrs. Leskowski disapprove of Mark's friends bringing their girlfriends over for a quickie in their rec room."

"Puh-lease," Ruth said as we cruised out of the parking lot and turned onto High School Road. "Why would any of them kill Amber? Or try to kill Heather? They're all friends, right?"

Right. Ruth was right. Ruth was always right. And I was always wrong. Well, almost always, anyway.

I guess I didn't really believe—in spite of what Tisha had told me, about all of them knowing about the house on the pit road—that they'd actually been involved in Amber's murder and Heather's attack. I mean, seriously: Mark Leskowski, wrapping his hands around his girlfriend's neck and strangling her? No way. He'd loved her. He'd cried in the guidance office in front of me, he'd loved her so much.

At least, I think that's why he'd been crying. He certainly hadn't been crying about his chances at winning a scholarship being endangered by his status as a murder suspect. I mean, that would have been just plain cold. Right?

And what about Heather? Did I suppose that Jeff Day or someone else on the team had tied Heather up and left her in that bathtub to die? Why? So she wouldn't narc on Mark?

No. It was ridiculous. Tisha's theory about the deranged hillbillies made more sense. Maybe the cheerleaders and the football team parried in the house on the pit road, but they weren't the ones who'd left Heather there. No, that had been the work of someone else. Some sick, perverted individual.

But not—absolutely not—my brother.

I made sure of that, the second I got home. Not, of course, that I'd had any reason to doubt it. I just wanted to set the record straight. I stalked up the stairs—my mother wasn't home, thank God, so I didn't have to listen to any more lectures about how unsuitable it was of me to sneak out in the middle of the night with a boy who worked in a garage—and banged once on Douglas's bedroom door. Then I threw it open, because Douglas's bedroom door doesn't have a lock. My dad took the lock off, after he slit his wrists in there and we had to break the door down to get to him.

He's so used to me barging in, he doesn't even look up anymore.

"Get out," he said, without lifting his gaze from the copy of Starship Troopers he was perusing.

"Douglas," I said. "I have to know. Where were you last night from five o'clock until eight, when you came back to the house?"

He looked up at that. "Why do I have to tell you?" he wanted to know.

"Because," I said.

I wanted to tell him the truth, of course. I wanted to say, Douglas, the Feds think you may have had something to do with Amber Mackey's murder, and Heather Montrose's attack. I need you to tell me you didn't do it. I need you to tell me that you have witnesses who can verify your whereabouts at the time these crimes occurred, and that your alibi is rock solid. Because unless you can tell me these things, I may have to take an after-school job working with some particularly nasty people.

In other words, the FBI.

But I wasn't sure I could say these things to Douglas. I wasn't sure I could say these things to Douglas because it was hard to tell anymore what might set off one of his episodes. Most of the time, he seemed normal to me. But every once in a while, something would upset him—something seemingly stupid, like that we were out of Cheerios—and suddenly the voices—Douglas's voices—were back.

On the other hand, this was something serious. It wasn't about Cheerios or reporters from Good Housekeeping magazine standing in our yard wanting to interview me. Not this time. This time, it was about people dying.

"Douglas," I said. "I mean it. I need to know where you were. There's this rumor going around—I don't believe it or anything—but there's this rumor going around that you killed Amber Mackey, and that last night you kidnapped Heather Montrose and left her to die."

"Whoa." Douglas, who was lying on his bed, put down his comic book. "And how did I do this, supposedly? Using my superpowers?"

"No," I said. "I think the theory is that you snapped."

"I see," Douglas said. "And who is promoting this theory?"

"Well," I said, "Karen Sue Hankey in particular, but also most of the junior class of Ernie Pyle High, along with some of the seniors, and, um, oh, yeah, the Federal Bureau of Investigation."

"Hmmm." Douglas considered this. "I find that last part particularly troubling. Does the FBI have proof or something that I killed these girls?"

"It's just one girl that's dead," I said. "The other one just got beat up."

"Well, why can't they ask her who beat her up?" Douglas wanted to know. "I mean, she'll tell them it wasn't me."

"She doesn't know who did it," I said. "She said they wore masks. And I figure even if she did know, she's not going to say. I am assuming whoever did this to her told her he'd finish the job if she talked."

Douglas sat up. "You're serious," he said. "People really do suspect me of doing this?"

"Yeah," I said. "And the thing is, the Feds are saying that unless I, you know, become a junior G-man, they're going to pin this thing on you. So before I sign up for my pension plan, I need to know. Have you got any kind of alibi at all?"

Douglas blinked at me. His eyes, like mine, were brown.

"I thought," he said, "that you'd told them you lost your psychic abilities."

"I did," I said. "I think my finding Heather Montrose in the middle of nowhere last night kind of tipped them off that maybe I hadn't been completely up front with them on that particular subject."

"Oh." Douglas looked uncomfortable. "The thing is, what I was doing last night . . . and the night that other girl disappeared . . . well, I was sort of hoping nobody would find out."

I stared at him. My God! So he had been up to something! But not, surely, lying in wait at that house on the pit road for an innocent cheerleader to go strolling by. . . .

"Douglas," I said. "I don't care what you were doing, so long as it didn't involve anything illegal. I just need something—preferably the truth—to tell Allan and Jill, or my butt is going to have 'Property of the U.S. Government' on it for the foreseeable future. So long as they have something on you, they own me. So I have to know. Do they have something on you?"

"Well," Douglas said, slowly. "Sort of...."

I could feel my world tilting, slowly … so slowly . . . right off its axis. My brother, Douglas. My big brother Douglas, whom all my life, it seemed, I'd been defending from others, people who called him retard, and spaz, and dorkus. People who wouldn't sit near him when we went to the movies as kids because sometimes he shouted things—that usually didn't make sense to everyone else—at the screen. People who wouldn't let their kids swim in the pool near him, because sometimes Douglas simply stopped swimming and just sank to the bottom, until a lifeguard noticed and fished him out. People who, every time a bike, or a dog, or a plaster yard gnome disappeared from the neighborhood, accused Douglas of having been the one who'd taken it, because Douglas . . . well, he wasn't all there, was he?

Only of course they were wrong. Douglas was all there. Just not in the way they considered normal.

But maybe, all this time … maybe they'd been right. Maybe this time Douglas really had done something wrong. Something so wrong, he didn't even want to tell me about it. Me, his kid sister, the one who'd learned how to swing a punch when she turned seven, just so that she could knock the blocks off the kids down the street who were calling him a freakazoid every time he passed by their house on the way to school.

"Douglas," I breathed, finding that my throat had suddenly, and inexplicably, closed. "What did you do?"

"Well," he said, unable to meet my gaze. "The truth is, Jess . . . the truth is . . ." He took a deep breath.

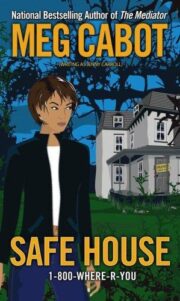

"Safe House" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Safe House". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Safe House" друзьям в соцсетях.