"Yes," Special Agent Smith said. "Did Douglas tell you where you could find Heather, Jessica? Is that how you knew to look in the house on the pit road?"

"Oh!" I stood up so fast, my chair tipped over backwards. "That's it. That is so it. End of interview. I am out of here."

"Why are you so angry, Jessica?" Special Agent Johnson, not moving from his chair, asked me. "Could it be perhaps because you think we might be right?"

"In your dreams," I said. "You are not pinning this one on Douglas. No way. Ask Heather. Go ahead. She'll tell you it wasn't Douglas."

"Heather Montrose did not see her attackers," Special Agent Johnson said lightly. "Something heavy was thrown over her head, she says, and then she was locked in a small enclosed space—presumably a car trunk—until some time after nightfall. When she was released, it was by several individuals in ski masks, from whom she attempted to escape—but who dissuaded her most emphatically. She can only say that their voices sounded vaguely familiar. She recalls very little, other than that."

I swallowed. Poor Heather.

Still, as a sister, I had a job to do.

"It wasn't Douglas," I said vehemently. "He doesn't have any friends. And he certainly has never owned a ski mask."

"Well, it shouldn't be hard to prove he had nothing to do with it," Special Agent Smith said. "I suppose he was in his room the whole time, as usual. Right, Jessica?"

I stared at them. They knew. I don't know how, but they knew. They knew Douglas hadn't been in the house when Heather had disappeared.

And they also knew I hadn't the slightest idea where he'd been, either.

"If you guys," I said, feeling so mad it was a wonder smoke wasn't coming out of my nostrils, "even think about dragging Douglas into this, you can kiss good-bye any hope you might have of me ever coming to work for you."

"What are you saying, Jessica?" Special Agent Johnson asked. "That you do, indeed, still have extrasensory perception?"

"How did you know where to find Heather Montrose, Jessica?" Jill asked in a sharp voice.

I went to the door. When I got to it, I turned around to face them.

"You stay away from Douglas," I said. "I mean it. If you go near him—if you so much as look at him—I'll move to Cuba, and I'll tell Fidel Castro everything he ever wanted to know about your undercover operatives over there."

Then I flung the door open and stalked out into the hallway.

Well, they couldn't stop me. I wasn't under arrest, after all.

I couldn't believe it. I really couldn't. I mean, I knew the United States government was eager to have me on its payroll, but to stoop to suggesting that if I did not come to their aid, they would frame my own brother for a crime he most certainly did not commit . . . well, that was low. George Washington, I knew, would have hung his head in shame if he'd heard about it.

When I got to the waiting area, I was still so mad I almost went stalking right through it, right out the door and on down the street. I couldn't see properly, I was so mad.

Or maybe it was because I'd just gone for so long without sleep. Whatever the reason, I stalked right past Rob and my parents, who were waiting for me—on different sides of the room—in front of the duty desk.

"Jessica!"

My mother's cry roused me from my fury. Well, that and the fact that she flung her arms around me.

"Jess, are you all right?"

Caught up in the stranglehold that served as my mother's excuse for a hug, I blinked a few times and observed Rob getting up slowly from the bench he'd been stretched out across.

"What happened?" my mom wanted to know. "Why did they keep you in there for so long? They said something about you finding a girl—another cheerleader. What's this all about? And what on earth were you doing out so late?"

Rob, across the room, smiled at the eye-roll I gave him behind my mother's back. Then he mouthed, "Call me."

Then he—very tactfully, I thought—left.

But not tactfully enough, since my dad went, "Who was that boy over there? The one who just left?"

"No one, Dad," I said. "Just a guy. Let's go home, okay? I'm really tired."

"What do you mean, just a guy? That wasn't even the same boy you were with earlier. How many boys are you seeing, anyway, Jessica? And what, exactly, were you doing out with him in the middle of the night?"

"Dad," I said, taking him by the arm and trying to physically propel him and my mother from the station house. "I'll explain when we get to the car. Now just come on."

"What about the rule?" my father demanded.

"What rule?"

"The rule that states you are not to see any boy socially whom your mother and I have not met."

"That's not a rule," I said. "At least, nobody ever told me about it before."

"Well, that's just because this is the first time anyone's asked you out," my dad said. "But you can bet there are going to be some rules now. Especially if these guys think it's all right for you to sneak out at night to meet with them—"

"Joe," my mother whispered, looking around the empty waiting room nervously. "Not so loud."

"I'll talk as loud as I want," my dad said. "I'm a taxpayer, aren't I? I paid for this building. Now I want to know, Toni. I want to know who this boy is our daughter is sneaking out of the house to meet...."

"God," I said. "It's Rob Wilkins." I was more glad than I could say that Rob wasn't around to hear this. "Mrs. Wilkins's son. Okay? Now can we go?"

"Mrs. Wilkins?" My dad looked perplexed. "You mean Mary, the new waitress at Mastriani's?"

"Yes," I said. "Now let's—"

"But he's much too old for you," my mother said. "He's graduated already. Hasn't he graduated already, Joe?"

"I think so," my dad said. You could tell he was totally uninterested in the subject now that he knew he employed Rob's mother. "Works over at the import garage, right, on Pike's Creek Road?"

"A garage?" my mother practically shrieked. "Oh, my God—"

It was, I knew, going to be a long drive home.

"This," my father said, "had better have been one of those ESP things, young lady, or you—"

And an even longer day.

C H A P T E R

14

I didn't get to school until fourth period.

That's because my parents, after I'd explained about rescuing Heather, let me sleep in. Not that they were happy about it. Good God, no. They were still excessively displeased, particularly my mother, who did NOT want me hanging out anymore with a guy who had no intention, now or ever, of going to college.

My dad, though … he was cool. He was just like, "Forget it, Toni. He's a nice kid."

My mom was all, "How would you know? You've never even met him."

"Yeah, but I know Mary," he said. "Now go get some sleep, Jessica."

Except that I couldn't. Sleep, that is. In spite of the fact that I lay in my bed from five, when I finally crawled back into it, until about ten thirty. All I could think about was Heather and that house. That awful, awful house.

Oh, and what Special Agent Johnson had said, too. About Douglas, I mean.

All Douglas's voices ever do is tell him to kill himself, not other people.

So it didn't make sense, what Special Agent Johnson was suggesting. Not for a minute.

Besides, Douglas didn't even drive. I mean, he had a license and a car and all.

But since that day they'd called us—last Christmas, when Douglas had had the first of his episodes, up where he was going to college—and we went to get him, and Mike drove his car back, it had sat, cold and dead, under the carport. Even Mike—who'd have given just about anything for a car of his own, having stupidly asked for a computer for graduation instead of a car, with which he might have enticed Claire Lippman, his lady love, on a date to the quarries—wouldn't touch Douglas's car. It was Douglas's car. And Douglas would drive it again one day.

Only he hadn't. I knew he hadn't because when I went outside, after Mom offered to give me a lift to school, I checked his tires. If he'd been driving around out by that pit house, there'd have been gravel in them.

But there wasn't. Douglas's wheels were clean as a whistle.

Not that I'd believed Special Agent Johnson. He'd just been saying that about Douglas to see if I maybe knew who the real killer was and just wasn't telling, for some bizarre reason. As if anybody who knew the identity of a murderer would go around keeping it a secret.

I am so sure.

I got to Orchestra in the middle of the strings' chair auditions. Ruth was playing as I walked in with my late pass in hand. She didn't notice me, she was so absorbed in what she was playing, which was a sonata we'd learned at music camp that summer. She would, I knew, get first chair. Ruth always gets first chair.

When she was done, Mr. Vine said, "Excellent, Ruth," and called the next cellist. There were only three cellists in Symphonic Orchestra, so it wasn't like the competition was particularly rough. But we all had to sit there and listen while people auditioned for their chairs, and let me tell you, it was way boring. Especially when we got to the violins. There were about fifteen violinists, and they all played the same thing.

"Hey," I whispered, as I pretended to be rooting around in my backpack for something.

"Hey," Ruth whispered back. She was putting her cello away. "Where were you? What's going on? Everyone is saying you saved Heather Montrose from certain death."

"Yeah," I said modestly. "I did."

"Jeez," Ruth said. "Why am I always the last to know everything? So where was she?"

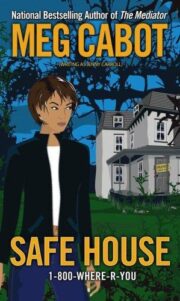

"Safe House" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Safe House". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Safe House" друзьям в соцсетях.