I like to think that the same could be said of him. And you know, the way he'd reacted when he'd heard I'd been out with another guy was kind of indicative that maybe he did like me as more than just a friend.

But I could no sooner rejoice over this realization than I could enjoy our ride. That, of course, was because of what I knew lay at the end of it. The road, I mean.

We did not encounter a single other vehicle along the way. Not until we reached the turnoff for the quarry, and saw a lone squad car sitting there with its interior light on as the officer within studied something attached to a clipboard. Rob slowed automatically as we approached—a speeding ticket he did not need—but didn't stop. His distrust of law enforcement agents is almost as finely honed as mine, only with better reason, since he'd actually been on the inside.

When we'd gotten far enough past the sheriff's deputy that we could pull over without him seeing us, Rob did say, keeping the motor running as he asked, "You want to ask him to join us?"

"Not yet," I said. "I'd rather … I want to make sure first."

Even though I was sure. Unfortunately, I was really sure.

"All right," Rob said. "Where to now?"

I pointed into the thick woods off to the side of the road. The thick, dark, seemingly impenetrable woods to the side of the wood.

"Great," Rob said without enthusiasm. Then he put down his helmet's visor again and said, "Hang on."

It was slow going. The floor of the woods was soft with decaying leaves and pine needles, and the trees, only a few feet apart, made a challenging obstacle course. We could only see what was directly in front of the beam from the Indian's headlamp, and basically, all that was was trees, and more trees. I pulled back the sleeve of Rob's leather jacket and pointed whenever we needed to change directions.

Don't ask me, either, how I knew where we going, me—who can't read a map to save my life and who's managed to flunk my driving test twice. God knew I had never been in these woods before. I was not allowed, like Claire Lippman, to swim in the quarries, and had never been to them before. There was a reason swimming here was illegal, and that was because the dark, inviting water was filled with hidden hazards, like abandoned farm equipment with sharp spikes sticking up, and car batteries slowly leaking acid into the county's groundwater.

Sounds like paradise, huh? Well, to a bunch of teenagers who weren't allowed to drink beside their parents' pools, it was.

So even though I had never been here before, it was like . . . well, it was like I had. In my mind's eye, as Douglas would say, I had been here, and I knew where we going. I knew exactly.

Still, when we hit the road again, I was surprised. It wasn't even a road, exactly, just a strip of land that, decades before, had become flattened by the heavy limestone-removing equipment that had passed over it, day after day. Now it was really just a grass-strewn pair of ruts. Ruts that led up to a dirty, abandoned-looking house, all of the windowpanes of which were dark—and busted out—and which had a DANGER—KEEP OUT sign attached to the front door.

I signaled for Rob to stop, and he did. Then we both sat and stared at the house in the beam from his headlight.

"You have got," Rob said, switching off the engine, "to be kidding me."

"No," I said. I took off my helmet. "She's in there. Somewhere."

Rob pulled his own helmet from his head and sat for a minute, staring at the house. No sound came from it—or from anywhere, actually—except the chirping of crickets and the occasional hoo-hoo of an owl.

"Is she dead?" Rob asked. "Or alive?"

"Alive," I said. Then I swallowed. "I think."

"Is anybody in there with her?"

"I don't … I don't know."

Rob looked at the house for a minute more. Then he said, "Okay," and swung off the bike. He went to the back storage compartment and dug around in it. In the glow of the bike's head lamp and the dim light afforded from the tiny sliver of moon, I saw him pull out the flashlight, and something else.

A lug wrench.

He noticed the direction of my gaze.

"It never hurts," he said, "to be prepared."

I nodded, even though I doubted he could see this small gesture in the minimal moonlight.

"Okay," he said, closing the lid to the storage compartment and turning around to face me. "Here's how it's going to go down. I'm going to go in there and look around. If you don't hear from me in five minutes—oh, here, take my watch—you get on this bike and you go for that cop car we saw. Understand?"

I took his watch, but shook my head as I slipped it into the pocket of his leather jacket.

"No," I said. "I'm coming with you."

Rob's expression—what I could see of it, anyway—was eloquent with disapproval.

"Mastriani," he said. "Wait here. I'll be all right."

"I don't want to wait here." I couldn't, I knew very well, send him in to do what by rights should only have been done by me. I'd had the vision. I should be the one to go into the creepy house to see if the vision was real. "I want to come with you."

"Jess," Rob said. "Don't do this."

"I'm coming with you," I said. To my surprise, my voice broke. Really. Just like Tisha's had, when she'd gone into hysterics outside the Chocolate Moose. Was I, I wondered, going into hysterics?

If Rob heard the break in my voice, he gave no sign.

"Jess," he said, "you're staying here with the bike, and that's final."

"And what if," I asked, the break having turned into a throb, "they come back—if they aren't in there now—and find me out here all alone?"

I did not, of course, even remotely believe that this might happen, or that, in the unlikely event that it did, I would not be able to get away on the Indian, which went from zero to sixty in mere seconds, thanks to Rob's dedicated tinkering.

My question did, however, have the desired effect on Rob, in that he sighed and, hooking the lug wrench through one of the belt loops of his jeans, reached out and took my hand.

"Come on," he said, though he didn't look too happy about it.

The steps to the house's tiny front porch were nearly rotted through. We had to step carefully as we climbed them. I wondered who had lived here, if anyone. It might, I thought, have served as the management office during the time the limestone had been carved out of the quarry down the road. Certainly no one had lived in it for years. . . .

Though someone had certainly been inside recently, because the door, which had been nailed shut, swung easily under Rob's palm. In the bright beam from the Indian's headlamp, I could see the shiny points of the nails gleaming where they'd been pried from the wood, while their heads were nearly rusted through with weather and age.

Rob, shining his flashlight into the dank blackness past the door, muttered, "I have a really bad feeling about this."

I didn't blame him. I had a pretty creepy feeling about it myself. All I could hear were the crickets outside and the drumming of my own heart. And one other sound, much fainter than the other two. But, unfortunately, familiar. A dripping sound. Like water from a faucet that had not been properly shut off.

The drip, drip, drip from my dream.

I mean, my nightmare. Heather's reality.

Rob took a firmer grip on my hand, and we stepped inside.

We were not the first ones to have done so recently. Not by a long shot. In the first place, animals had clearly been making use of the space, leaving scattered droppings and nests of leaves and sticks all over the rotting wooden floor.

But raccoons and opossums weren't the dilapidated building's most recent tenants. Not if the many beer bottles and crumpled bags of chips on the floor were any indication. Someone had been doing some major partying. I could even smell, faintly, the intoxicating scent of human vomit.

"Nice," Rob said as we picked our way across the floor toward the only door, which hung crazily on its hinges. He paused and, letting go of my hand for a second, stooped to pick up a beer bottle.

"Imported," he said, reading the label by flashlight. Then he put the bottle down again. "Townies," he said, taking my hand again. "It figures."

The next room had apparently been a kitchen, but all of the fixtures were gone, except for a few rusted-out cabinets and a gas oven that looked beyond repair. There were less animal droppings in the kitchen, but more beer bottles, and, interestingly, a pair of pants. They were too big—and unstylish—to have belonged to Heather, so we continued our tour.

The kitchen led to the third and what I thought was the final room. This one had a fireplace, in which rested an empty keg.

"Someone," Rob said, "didn't care whether or not he got his deposit back."

That's when I noticed the stairs and tightened my grip on Rob's hand.

He followed the direction of my gaze, and sighed.

"Of course," he said. "Let's go."

The stairs were in only a little better condition than the porch steps. We climbed them slowly, taking care where we put each foot. One wrong step, and we'd have fallen through. As we climbed, the dripping sound grew steadily louder. Please, I prayed. Don't let that be blood.

The second floor consisted of three rooms. The first, to the left, had obviously been a bedroom at one time. There was still a mattress on the floor, though a mattress covered with so many stains and discolorations that I'd have only touched it with latex gloves on. A crunching noise beneath our feet revealed that my fears had not been ill-founded. There were condom wrappers everywhere.

"Well," Rob remarked, "at least they're practicing safe sex."

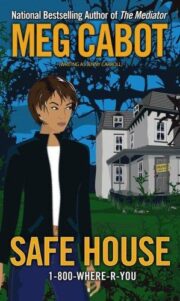

"Safe House" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Safe House". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Safe House" друзьям в соцсетях.