"Sit," the old lady commanded. Nina nodded at the easy chair on our left and I went to it. She went to the other.

"Nina . . ." I began.

"Shh," she said and closed her eyes. "Just wait." A moment later, from somewhere else in the house, I heard the sound of a drum. It was a low, steady beat. I couldn't help but become nervous and afraid. Why had I allowed myself to be brought here?

Suddenly, the blanket that hung in the doorway in front of us parted and a much younger looking black woman appeared. She had long, silky black hair gathered in thick ropelike strands around her head, over which she wore a red tignon with seven knots whose points all stuck straight up. She was tall and wore a black robe that flowed all the way down to her bare feet. I thought she had a pretty face, lean with high cheekbones and a nicely shaped mouth, but when she turned to me, I shuddered. Her eyes were as gray as granite.

She was blind.

"Mama Dede, I come for big help," Nina said. Mama Dede nodded and entered the room, moving as if she weren't blind, swiftly and gracefully sitting herself on the settee. She folded her hands in her lap and waited, those seemingly dead eyes turning toward me. I didn't move; hardly breathed.

"Speak of it, sister," she said.

"This little girl here, she's got a twin sister, jealous and cruel, who does bad things to her causing much pain and grief."

"Give me your hand," Mama Dede said to me, and held hers out. I looked at Nina who nodded. Slowly, I put mine into Mama Dede's. She closed her fingers firmly over mine. They felt hot.

"Your sister," Mama Dede said to me. "You don't know her long and she don't know you long?"

"Yes, that's right," I said amazed.

"And your mother, she can't help you none?"

"No."

"She be dead and gone to the other side," she said, nodding and then she released my hand and turned to Nina.

"Papa La Bas, he eating on her sister's heart," Nina said. "Making her hateful, somethin' terrible. Now we got to protect this baby, Mama. She believes. Her Grandmère was a Traiteur lady in the bayou."

Mama Dede nodded softly and then held out her hand again, this time—palm up. Nina dug into her pocket and pulled out a silver dollar. She put it in Mama Dede's hand. Mama Dede closed her palm and then turned to the doorway where the old lady stood watching. She came forward and took the silver coin and dropped it in a pocket in her sack dress.

"Burn two yellow candles," she prescribed. The old lady moved to the cartons and plucked out two yellow candles. She set them in holders and then lit their wicks. I thought that might be all there was to it, but suddenly, Mama Dede reached out and seized the top of the ornate box. She lifted it gently and put it beside her on the settee. Nina looked very happy. I waited as Mama Dede concentrated and then dipped her hands into the box. When she brought them up, I nearly fainted.

She was clutching a young python snake. It seemed asleep, barely moving, its eyes just two slits. I gulped to keep down a scream as Mama Dede brought the snake to her face.

Instantly, the snake's tongue jetted out and it licked her cheek. As soon as it had, Mama Dede returned it to the box and covered the box again.

"From the snake, Mama Dede gets the power and the vision," Nina whispered. "Old legend say, first man and first woman entered the world blind and were given sight by the snake."

"What's your sister's name, child?" Mama Dede asked. My tongue tightened. I was afraid to give it, afraid now that something terrible might occur.

"You must be the one to give the name," Nina instructed. "Give Mama Dede the name."

"Gisselle," I said. "But . . ."

"Eh! Eh bomba hen hen!" Mama Dede began to chant. As she chanted, she turned and twisted her body under the robe, writhing to the sound of the drum and the rhythm of her own voice.

"Canga bafie te. Danga moune de te. Canga do ki Gisselle!" she ended with a shout.

My heart was pounding so hard, I had to press the palm of my hand against my breast. Mama Dede turned toward Nina again. She reached into her pocket and produced what I recognized as one of Gisselle's hair ribbons. That was why she had first gone upstairs before we left. I wanted to reach out and stop her before she put it into Mama Dede's hand, but I was too late. The voodoo queen clutched it tightly.

"Wait," I cried, but Mama Dede opened the box and dropped the ribbon into it.

Then she writhed again and began a new chant.

"L'appe vini, Le Grand Zombi. L'appe vini, pou fe gris-gris."

"He is coming," Nina translated. "The Great Zombi, he is coming, to make gris-gris."

Mama Dede paused suddenly and screamed a piercing cry that made my heart stop for a moment. I thought it had risen into my throat. I couldn't swallow; I could barely breathe. She froze and then she fell back against the settee, dropping her head to the side, her eyes closed. For a moment no one moved, no one spoke. Then Nina tapped me on the knee and nodded toward the door. I rose quickly. The old lady moved ahead and opened the front door for us.

"Thank Mama, please, Grandmère," Nina said. The old lady nodded and we left.

My heart didn't stop racing until we reached home again. Nina was so confident everything would be all right now. I couldn't imagine what to expect. But when Gisselle returned from school, she wasn't a bit changed. In fact, she bawled me out for running away and blamed me for everything that happened as a result.

"Because you ran off like that, Beau got into a fight with Billy and they were both taken to the principal," she said, stopping in the doorway of my room. "Beau's parents have to come to school before he can return.

"Everyone thinks you're crazy now. It was all just a joke. But I got called into the principal's office, too, and he's going to call Daddy and Mommy, thanks to you. Now we'll both be in trouble."

I turned to her slowly, my heart so full of anger, I didn't think I would be able to speak without screaming. But I surprised myself and frightened her with the control in my voice.

"I'm sorry Beau got into a fight and into trouble. He was only trying to protect me. But I'm not sorry about you.

"It's true, I lived in a world that most would consider quite backward compared to the one you've lived in, Gisselle. And it's true the people are simpler and things happen that city people think are terrible, crude, and even immoral.

"But the cruel things you've done to me and permitted others to do to me make anything I've seen in the bayou look like child's play. I thought we could be sisters, real sisters who looked out for each other and cared for each other, but you're determined to hurt me any way you can and whenever you can," I said. Tears were streaming down my cheeks now, despite my effort not to cry in front of her.

"Sure," she replied, moans in her voice, too. "You're making me out to be the bad one now. But you're the one who just appeared on our doorstep and turned our world topsy-turvy. You're the one who got everyone to like you more than they like me. You stole Beau, didn't you?"

"I didn't steal him. You told me you didn't care about him anymore anyway," I said.

"Well . . . I don't, but I don't like someone stealing him away," she added. She stood there, fuming for a few moments. "You better not get me in trouble when the principal calls," she warned and marched off.

Dr. Storm did call. After breaking up the fight between Beau and Billy, a teacher had taken the photograph and brought it to the principal. Dr. Storm told Daphne about the picture and she called Gisselle and me into the study just before dinner. She was so full of anger and embarrassment, her face looked distorted: her eyes large and furious, her mouth stretched into a grimace and her nostrils wide.

"Which one of you allowed such a picture to be taken?" she demanded. Gisselle looked down quickly.

"Neither of us allowed it, Mother," I said. "Some boys snuck into Claudine's house without any of us knowing and while I was changing into a costume for a game we were playing, they snapped the picture of me."

"We're the laughingstock of the school community by now, I'm sure," she said. "And the Andreas have to see the principal. I just got off the phone with Edith Andreas. She's beside herself. This is the first time Beau has gotten into serious trouble. And all because of you," she accused.

"But . . ."

"Did you do these sorts of things in the swamp?"

"No. Of course not," I replied quickly.

"I don't know how you get yourself involved in one terrible thing after another so quickly, but you apparently do. Until further notice, you are not to go anywhere, no parties, no dates, no expensive dinners, nothing. Is that understood?"

I choked back my tears. Defending myself was useless. All she could see was how she had been disgraced.

"Yes, Mother."

"Your father doesn't know about this yet. I will tell him calmly when he returns. Go upstairs and remain in your room until it's time to come down for dinner."

I left and went upstairs, feeling strangely numb. It was as if I didn't care anymore. She could do whatever she wanted to do to me. It didn't matter.

Gisselle paused in my doorway on the way back to her room. She flashed a smile of self-satisfaction, but I didn't say a word to her. That night, we had the quietest dinner since I had arrived. My father was subdued by his disappointment and by what I was sure was Daphne's rage. I avoided his eyes and was happy when Gisselle and I were excused. She couldn't wait to get to her telephone to spread the news of what had occurred.

I went to sleep that night, thinking about Mama Dede, the snake, and the ribbon. How I wished there was something to it all. My desire for vengeance was that strong.

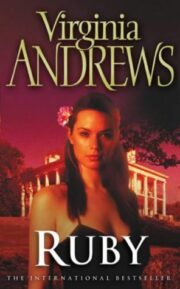

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.