Shocked by what she said, I tried to meet her eyes and hold them, but she refused to look at me, afraid once she did, she couldn't look away.

Daphne widened her eyes and nodded at my father who shook his head.

"I didn't say you were in trouble. I just said I was disappointed in you two, that's all," he replied. "Ruby," he said, turning back to me. "I know that alcoholic beverages were common in your household."

I started to shake my head.

"But we have a different view of that here. There's a time and a place for imbibing and young girls should never do it on their own. Next thing you know, one of your boyfriends gets drunk and everyone gets into the car with him and . . . I just don't like to think what could happen."

"Or what young girls can be talked into doing after they've consumed alcohol," Daphne added. "Don't forget that aspect," she advised my father. He nodded obediently.

"Your mother is right, girls. It's just not a good idea. Now, I'm willing to forgive everyone, put this bad incident aside, as long as I have your solemn promise, both of your solemn promises, that nothing like this will occur again."

"I promise," Gisselle said quickly. "I didn't want to do it anyway. I had a terrible headache this morning. Some people are used to drinking a lot of alcohol and some are not," she added, throwing a glance at me.

"That's very true," Daphne said, glaring at me. I looked away so that no one would see how much I was fuming inside. The heat that built itself up in my chest felt as if it could burn a hole through me.

"Ruby?" my father asked. I swallowed hard to keep my tears from choking me and forced out the words.

"I promise," I said.

"That's good. Now then," he began, but before he could continue, we heard the door chimes. He looked at his watch. "I expect that is Ruby's art instructor," he said.

"Under the circumstances," Daphne said, "don't you think you should postpone this?"

"Postpone? Well . ." He looked at me and I looked down quickly. "We can't just turn the man away. He's giving his time, traveled here—"

"You shouldn't have been so impulsive," Daphne said. "Next time, I would like you to discuss it with me before you give the girls anything or do anything for them. After all," she said firmly, "I am their mother."

My father pressed his lips together as if to shut up any words in his mouth and nodded.

"Of course. It won't happen again," he assured her.

"Excuse me, monsieur," Edgar said, coming to the doorway, "but a Professor Ashbury has arrived.

His card," he said, handing the card to my father.

"Show him in, Edgar."

"Very good, monsieur," he said.

"I don't think you need me for this," Daphne said. "I have some phone calls to return. As you predicted, everyone and anyone who knows us wants to hear the story of Ruby's disappearance and arrival. Telling the story repeatedly is proving to be exhausting. We should have it printed and distributed," she added, spun on her heels and marched out of the study.

"I've got to go take a couple of aspirins," Gisselle said, sitting up quickly. "You can tell me about your instructor later, Ruby," she said, smiling at me. I didn't smile back. As she left the study, Edgar brought in Professor Ashbury, so I had no time to tell my father the truth about what had occurred the night before.

"Professor Ashbury, how do you do?" my father said, extending his hand.

Looking like he was in his early fifties, Herbert Ashbury stood about five-feet-nine and wore a gray sports jacket, a light blue shirt, a dark blue tie, and a pair of dark blue jeans. He had a lean face, all of his features sharply cut, his nose angular and a bit long, his mouth thin and smooth like a woman's.

"How do you do, Monsieur Dumas," the professor said in what I thought was a rather soft voice. He extended a long hand with fingers that enveloped my father's hand when they shook. He wore a beautifully hand crafted silver ring set with a turquoise on his pinky.

"Fine, thank you, and thank you for coming and agreeing to consider my daughter. May I present my daughter Ruby," Daddy said proudly, turning toward me.

Because of his narrow cheeks and the way his forehead sloped sharply back into his hairline, Professor Ashbury's eyes appeared larger than they were. Dark brown eyes with specks of gray, they seized onto whatever he was gazing at and held so firmly he looked mesmerized. Right now they fixed so tightly on my face, I couldn't help but be self-conscious.

"Hello," I said quickly.

He combed his long thin fingers through the wild strands of his thin light brown and gray hair, driving the strands off' his forehead, and flashed a smile, his eyes flickering for a moment and then growing serious again.

"Where have you had your art instruction up until now, mademoiselle?" he inquired.

"Just a little in public school," I replied.

"Public school?" he said, turning down the corners of his mouth as if I had said "reform school." He turned to my father for an explanation.

"That's why I thought it would be of great benefit to her at this time to have private instruction from a reputable and highly respected teacher," my father said.

"I don't understand, monsieur. I was told your daughter has had some of her works accepted by one of our art galleries. I just assumed . . ."

"That's true," my father replied, smiling. "I will show you one of her pictures. Actually, the only one in my possession at the moment."

"Oh?" Professor Ashbury said, a look of perplexity on his face. "Only one?"

"That's another story, Professor. First things first. Right this way," he instructed, and led the professor to his office where my picture of the blue heron still remained on the floor against his desk.

Professor Ashbury stared at it a moment and then stepped forward to pick it up.

"May I?" he asked Daddy.

"By all means, please."

Professor Ashbury lifted the picture and held it out at arm's length for a moment. Then he nodded and put it down slowly.

"I like that," he said, then turned to me. "You caught a sense of movement. It has a realistic feel and yet . . . there's something mysterious about it. There's an intelligent use of shading. The setting is rather well captured, too . . . Have you spent time in the bayou?"

"I lived there all of my life," I said.

Professor Ashbury's eyes lit with interest. He shook his head and turned to Daddy. "Forgive me, monsieur," he said, "I don't mean to sound like an interrogator, but I thought you had introduced Ruby as your daughter."

"I did and she is," Daddy said. "She didn't live with me until now."

"I see," he said, gazing at me again. He didn't seem shocked or surprised by the information, but he felt he had to continue to justify his interest in our personal lives. "I like to know something about my students, especially the ones I take on privately. Art, real art, comes from inside," he said, placing the palm of his right hand over his heart. "I can teach her the mechanics, but what she brings to the canvas is something no teacher can create or teach. She brings herself, her life, her experience, her vision," he said. "Do you understand, monsieur?"

"Er . . . yes," Daddy said. "Of course. You can learn all about her if you like. The main question is do you believe as some already have exhibited they do, that she has talent?"

"Absolutely," Professor Ashbury said. He looked at my picture again and then turned back to me. "She might be the best student I've ever had," he added.

My mouth gaped open and my father's face lit with pride. He beamed a broad smile and nodded.

"I thought so, even though I'm no art expert."

"It doesn't take an art expert to see what potential lies here," Professor Ashbury said, looking at my painting once more.

"Let me show you the studio then," my father said, and led Professor Ashbury and me down the corridor. The professor was very impressed, as anyone would be, I imagined.

"It's better than what I have at the college," he whispered as if he didn't want the college trustees to hear.

"When I believe in something or someone, Professor Ashbury, I commit myself fully," my father declared.

"I can see that. Very well, monsieur," he said with some pomposity, "I accept your daughter as one of my students. Provided, of course," he added, shifting his eyes to me, "she is willing to accept my tutelage completely and without question."

"I'm sure she is. Ruby?"

"What? Oh, yes. Thank you," I said quickly. I was still absorbing Professor Ashbury's earlier compliments.

"I will take you through the fundamentals once again," he warned. "I will teach you discipline, and only when I think you are ready, will I turn you loose on your own imaginative powers. Many are born with talent," he declared, "but few have the discipline to develop it properly."

"She does," my father assured him.

"We'll see, monsieur."

"Come to my office, Professor, and we will discuss the financial arrangements," my father said. Professor Ashbury, his eyes still fixed on me, nodded. "When can she have her first lesson with you, Professor?"

"This coming Monday, monsieur," he replied. "Although she has one of the finest home studios in the city, I might ask her to come to mine from time to time," he added.

"That won't be a problem."

"Trés Bien," Professor Ashbury said. He nodded at me and left with my father.

My heart was pounding with excitement. Grandmère Catherine had always been so positive about my artistic talent. She had no formal schooling and knew little about art, and yet she was convinced down to her soul that I would be a success. How many times had she assured me of this, and now, an art instructor, a professor at a college, had taken one look at my work and declared me very possibly his best candidate.

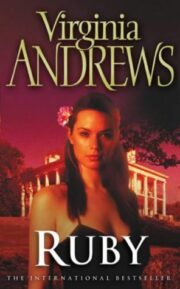

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.