"Of course it is," she replied. "What do you think love is . . . bells ringing, music in the breeze, a handsome, gallant man sweeping you off your feet with poetic promises he can't possibly keep? I thought you Cajuns were more practical minded," she said with that same tight smile. I felt my face turn zed, both from anger and embarrassment. Whenever she had something negative to say, I was a Cajun, but whenever she had something nice to say, I was a Creole blue blood, and she made Cajuns sound like such clods, especially the women.

"Up until now, I bet you've only had poor boyfriends. The most expensive gift they could probably give you was a pound of shrimp. But the boys who will be coming around now will be driving expensive automobiles, wearing expensive clothing, and casually be giving you presents that will make your Cajun eyes bulge," she said, and laughed.

"Look at the rings on my hand!" she exclaimed, lifting her right hand off the steering wheel. Every finger had a ring on it. There seemed to be one for every valuable jewel: diamonds, emeralds, rubies, and sapphires all set in gold and platinum. Her hand looked like a display in a jewelry shop window.

"Why I bet the amount of money I have on this hand would buy the houses and food for a year for ten swamp families."

"They would," I admitted. I wanted to add and that seems unfair, but I didn't.

"Your father wants to buy you some nice bracelets and rings himself, and he noted that you have no watch. With beautiful jewelry, nice clothes, and a little makeup, you will at least look like you've been a Dumas for your whole life. The next thing I'll do is take you through some simple rules of etiquette, show you the proper way to dine and speak."

"What's wrong with how I eat and talk?" I wondered aloud. My father hadn't appeared upset at breakfast or lunch.

"Nothing, if you lived the rest of your life in the swamps, but you're in New Orleans now and part of high society. There will be dinner parties and gala affairs. You want to become a refined, educated, and attractive young woman, don't you?" she asked.

I couldn't help wanting to be like her. She was so elegant and carried herself with such an air of confidence, and yet, every time I agreed to something she said or did something she wanted me to do, it was as if I were looking down upon the Cajun people, treating them as if they were less important and not as good.

I decided I would do what I had to do to make my father happy and blend into his world, but I wouldn't harbor any feelings of superiority, if I could help it. I was only afraid I would become more like Gisselle than, as my father wished, Gisselle would become more like me.

"You do want to be a Dumas, don't you?" she pursued.

"Yes," I said, but not with much conviction. My hesitation gave her reason to glance at me again, those blue eyes darkening with suspicion.

"I do hope you will make every effort to answer the call of your Creole blood, your real heritage, and quickly block out and forget the Cajun world you were unfairly left to live in. Just think," she said, a little lightness in her voice now, "it was just chance Gisselle was the one given the better life. If you would have emerged first from your mother's womb, Gisselle would have been the poor Cajun girl."

The idea made her laugh.

"I must tell her that she could have been the one kidnapped and forced to live in the swamps," she added. "Just to see the look on her face."

The thought brought a broad smile to hers. How was I to tell her that despite the hardships Grandmère Catherine and I endured and despite the mean things Grandpère Jack had done, my Cajun world had its charm, too?

Apparently, if it wasn't something she could buy in a store, it wasn't significant to her, and despite what she told me, love was something you couldn't buy in a store. In my heart I knew that to be true, and that was one Cajun belief she would never change, elegant, rich life at stake or not.

When we drove up to the house, she called Edgar out to take all the packages up to my room. I wanted to help him, but Daphne snapped at me as soon as I made the suggestion.

"Help him?" she said as if I had proposed burning down the house. "You don't help him. He helps you. That's what servants are fore my dear child. I'll see to it that Wendy hangs everything up that has to be hung up in your closet and puts everything else in your armoire and vanity table. You run along and find your sister and do whatever it is girls your age do on your days off from school."

Having servants do the simplest things for me was one of the hardest things for me to get used to, I thought. Wouldn't it make me lazy? But no one seemed concerned about being lazy here. It was expected of you, almost required.

I remembered that Gisselle said she would be out at the pool, lounging with Beau Andreas. They were there, lying on thick cushioned beige metal framed lounges and sipping from tall glasses of pink lemonade. Beau sat up as soon as he set eyes on me and beamed a warm smile. He was wearing a white and blue terry cloth jacket and shorts and Gisselle was in a two-piece dark blue bathing suit, her sunglasses almost big enough to be called a mask.

"Hi," Beau said immediately. Gisselle looked up, lowering and peering over her sunglasses as if they were reading glasses.

"Did Mother leave anything in the stores for anyone else?" she asked.

"Barely," I said. "I've never been to so many big department stores and seen so much clothing and shoes." Beau laughed at my enthusiasm.

"I'm sure she took you to Diana's and Rudolph Vita's and the Moulin Rouge, didn't she?" Gisselle said.

I shook my head.

"To tell you the truth, we went in and out of so many stores and so quickly, I don't remember the names of half of them," I said with a gasp. Beau laughed again and patted his lounge. He pulled his legs up, embracing them around the knees.

"Sit down. Take a load off," he suggested.

"Thanks." I sat down next to him and smelled the sweet scent of the coconut suntan lotion he and Gisselle had on their faces.

"Gisselle told me your story," he said. "It's fantastic. What were these Cajun people like? Did they turn you into their little slave or something?"

"Oh, no," I said, but quickly checked my enthusiasm. "I had my daily chores, of course."

"Chores," Gisselle moaned.

"I was taught handicrafts and helped make the things we sold at the roadside to the tourists, as well as helping with the cooking and the cleaning," I explained.

"You can cook?" Gisselle asked, peering over her glasses at me again.

"Gisselle couldn't boil water without burning it," Beau teased.

"Well, who cares? I don't intend to cook for anyone . . . ever," she said, pulling her eyeglasses off and flashing heat out of her eyes at him. He just smiled and turned back to me.

"I understand you're an artist, too," he said. "And you actually have paintings in a gallery here in the French Quarter."

"I was more surprised than anyone that a gallery owner wanted to sell them," I told him. His smile warmed, the gray-blue in his eyes becoming softer.

"So far my father is the only one who bought one, right?" Gisselle quipped.

"No. Someone else bought one first. That's how I got the money for my bus trip here," I said. Gisselle seemed disappointed, and when Beau gazed at her, she put her glasses on and dropped herself back on the lounge.

"Where is the picture your father bought?" Beau asked. "I'd love to see it."

"It's in his office."

"Still on the floor," Gisselle interjected. "He'll probably leave it there for months."

"I'd still like to see it," Beau said.

"So go see it," Gisselle said. "It's only a picture of a bird."

"Heron," I said. "In the marsh."

"I've been to the bayou a few times to fish. It can be quite beautiful there," Beau said.

"Swamps, ugh," Gisselle moaned.

"It's very pretty there, especially in the spring and the fall."

"Alligators and snakes and mosquitos, not to mention mud everywhere and on everything. Very beautiful," Gisselle said.

"Don't mind her. She doesn't even like going in my sailboat on Lake Pontchartrain because the water sprays up and gets her hair wet, and she won't go to the beach because she can't stand sand in her bathing suit and in her hair."

"So? Why should I put up with all that when I can swim here in a clean, filtered pool?" Gisselle proclaimed.

"Don't you just like going places and seeing new things?" I asked.

"Not unless she can strap her vanity table to her back," Beau said. Gisselle sat up so quickly it was as if she had a spring in her back.

"Oh, sure, Beau Andreas, suddenly you're a big naturalist, a fisherman, a sailor, a hiker. You hate doing most of those things almost as much as I do, but you're just putting on an act for my sister," she charged. Beau turned crimson.

"I do too like to fish and sail," he protested.

"When do you do it, twice a year at the most?"

"Depends," he said.

"On what, your social calendar or your hair appointment," Gisselle said sharply. Throughout the exchange, my gaze went from one to the other. Gisselle's eyes blazed with so much anger, it was hard to believe she thought of him as her boyfriend.

"You know he has a woman cut his hair at his house," Gisselle continued. The crimson tint in Beau's cheeks rushed down into his neck. "She's his mother's beautician and she even gives him a manicure every two weeks."

"It's just that my mother likes the way she does her hair," Beau said. "I . . ."

"Your hair is very nice," I said. "I don't think it's unusual for a woman to cut a man's hair. I used to cut my Grandpère's hair once in a while. I mean, the man I called Grandpère."

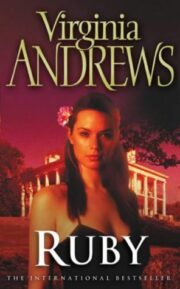

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.