"Really, Pierre," she said, "I haven't seen you this exuberant about anything for years."

"Well, I have good reason to be," he replied.

"I hate to be the one to insert a dark thought, but you realize you haven't spoken to Gisselle yet and told her your story about Ruby," she said.

He seemed to deflate pounds of excitement right before my eyes and then he nodded.

"You're right as always, my dear. It's time to wake the princess and talk to her," he said. He rose and picked up my picture. "Now where should we hang this? In the living room?"

"I think it would be better in your office, Pierre," Daphne said. To me it sounded as though she wanted it where it would be seen the least.

"Yes. Good idea. That way I can get to look at it more," he replied. "Well, here I go. Wish me luck," he said, smiling at me, and then he went into the house to talk to Gisselle. Daphne and I gazed at each other for a moment. Then she put down her coffee cup.

"Well now, you've made quite a beginning with your father, it seems," she said.

"He's very nice," I told her. She stared at me a moment.

"He hasn't been this happy for a while. I should tell you, since you have become an instant member of the family, that Pierre, your father, suffers from periods of melancholia. Do you know what that is?" I shook my head. "He falls into deep depressions from time to time. Without warning," she added.

"Depressions?"

"Yes. He can lock himself away for hours, days even, and not want to see or speak to anyone. You can be speaking to him and suddenly, he'll take on a far-off look and leave you in midsentence. Later, he won't remember doing it," she said. I shook my head. It seemed incredible that this man with whom I had just spent several happy hours could be described as she had described him.

"Sometimes, he'll lock himself in his office and play this dreadfully mournful music. I've had doctors prescribe medications, but he doesn't like taking anything.

"His mother was like that," she continued. "The Dumas family history is clouded with unhappy events."

"I know. He told me about his younger brother," I said. She looked up sharply.

"He told you already? That's what I mean," she said, shaking her head. "He can't wait to go into these dreadful things and depress everyone."

"He didn't depress me although it was a very sad story," I said. Her lips tightened and her eyes narrowed. She didn't like being contradicted.

"I suppose he described it as a boating accident," she said.

"Yes. Wasn't it?"

"I don't want to go into it all now. It does depress me," she added, eyes wide. "Anyway, I've tried and I continue to try to do everything in my power to make Pierre happy. The most important thing to remember if you're going to live here is that we must have harmony in our house. Petty arguments, little intrigues and plots, jealousies and betrayals have no place in the House of Dumas.

"Pierre is so happy about your existence and arrival that he is blind to the problems we are about to face," she continued. When she spoke, she spoke with such a firm, regal tone, I couldn't do anything but listen, my eyes fixed on her. "He doesn't understand the immensity of the task ahead. I know how different a world you come from and the sort of things you're used to doing and having."

"What sort of things, madame?" I asked, curious myself.

"Just things," she said firmly, her eyes sharp. "It's not a topic ladies like to discuss."

"I don't want or do anything like that," I protested.

"You don't even realize what you've done, what sort of life you've led up until now. I know Cajuns have a different sense of morality, different codes of behavior."

"That's not so, madame," I replied, but she continued as though I hadn't.

"You won't realize it until you've been . . . been educated and trained and enlightened," she declared.

"Since your arrival is so important to Pierre, I will do my best to teach you and guide you, of course; but I will need your full cooperation and obedience. If you have any problems, and I'm sure you will in the beginning, please come directly to me with them. Don't trouble Pierre.

"All I need," she added, more to herself than to me, "is for something else to depress him. He might just end up like his younger brother."

"I don't understand," I said.

"It's not important just now," she said quickly. Then she pulled back her shoulders and stood up.

"I'm going to get dressed and then take you shopping," she said. "Please be where I can find you in twenty minutes."

"Yes, madame."

"I hope," she said, pausing near me to brush some strands of hair off my forehead, "that in time you will become comfortable addressing me as Mother."

"I hope so, too," I said. I didn't mean it to sound the way it did—almost a threat. She pulled herself back a bit and narrowed her eyes before she flashed a small, tight smile and then left to get ready to take me shopping.

While I waited for her, I continued my tour of the house, stopping to look in on what was my father's office. He had placed my picture against his desk before going up to Gisselle. There was another picture of his father, my grandfather, I supposed, on the wall above and behind his desk chair. In this picture, he looked less severe, although he was dressed formally and was gazing thoughtfully, not even the slightest smile around his lips or eyes.

My father had a walnut writing desk, French cabinets, and ladder-back chairs. There were bookcases on both sides of the office, the floor of which was polished hardwood with a small, tightly knit beige oval rug under the desk and chair. In the far left corner there was a globe. Everything on the desk and in the room was neatly organized and seemingly dust free. It was as if the inhabitants of this house tiptoed about with gloved hands. All the furniture, the immaculate floors and walls, the fixtures and shelves, the antiques and statues made me feel like a bull in a china shop. I was afraid to move quickly, turn abruptly, and especially afraid to touch anything, but I entered the office to glance at the pictures on the desk.

In sterling silver frames, my father had pictures of Daphne and Gisselle. There was a picture of two people I assumed to be his parents, my grandparents. My grand-mother, Mrs. Dumas, looked like a small woman, pretty with diminutive features, but an overall sadness in her lips and eyes. Where, I wondered, was there a picture of my father's younger brother, Jean?

I left the office and found there was a separate study, a library with red leather sofas and high back chairs, gold leaf tables, and brass lamps. A curio case in the study was filled with valuable looking red, green, and purple hand blown goblets, and the walls, as were the walls in all the rooms, were covered with oil paintings. I went in and browsed through some of the books on the shelves.

"Here you are," I heard my father say, and I turned to see him and Gisselle standing in the doorway. Gisselle was in a pink silk robe and the softest looking pink slippers. Her hair had been hastily brushed and looked it. Pale and sleepy eyed, she stood with her arms folded under her breasts. "We were looking for you."

"I was just exploring. I hope it's all right," I said.

"Of course it's all right. This is your home. Go where you like. Well now, Gisselle understands what's happened and wants to greet you as if for the first time," he said, and smiled. I looked at Gisselle who sighed and stepped forward.

"I'm sorry for the way I behaved," she began. "I didn't know the story. No one ever told me anything like this before," she added, shifting her eyes toward our father, who looked sufficiently apologetic. "Anyway, this changes things a lot. Now that I know you really are my sister and you've gone through a terrible time."

"I'm glad," I said. "And you don't have to apologize for anything. I can understand why you'd be upset at me suddenly appearing on your doorstep."

She seemed pleased, gashed a look at father and then turned back to me.

"I want to welcome you to our family. I'm looking forward to getting to know you," she added. It had the resonance of something memorized, but I was happy to hear the words nevertheless. "And don't worry about school. Daddy told me you were concerned, 'But you don't have to be. No one is going to give my sister a hard time," she declared.

"Gisselle is the class bully," our father said, and smiled.

"I'm not a bully, but I'm not going to let those namby-pambies push us around," she swore. "Anyway, you can come into my room later and talk. We should really get to know each other."

"I'd like that."

"Maybe you want to go along with Ruby and Daphne to shop for Ruby's new wardrobe," our father suggested.

"I can't. Beau's coming over." She flashed a smile at me. "I mean, I'd call him and cancel, but he so looks forward to seeing me, and besides, by the time I get ready, you and Mother could be half finished. Come out to the pool as soon as you get back," she said.

"I will."

"Don't let Mother buy those horribly long skirts, the ones that go all the way down to your ankles. Everyone's wearing shorter skirts these days," she advised, but I couldn't imagine telling Daphne what or what not to buy me. I was grateful for anything. I nodded, but Gisselle saw my hesitation.

"Don't worry about it," Gisselle said. "If you don't get things that are in style, let you borrow something for your first day at school."

"That's very nice," our father said. "Thanks for being so understanding, honey."

"You're welcome, Daddy," she said, and kissed him on the cheek. He beamed and then rubbed his hands together.

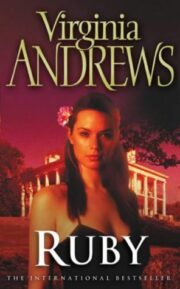

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.