"'Who is that?' I asked your grandfather.

"'Just my daughter,' he said.

"Just his daughter? I thought, a goddess who seemed to emerge from the bayou. Just his daughter?

"I couldn't help myself, you see. I was never so smitten. Every chance I had to be with her, near her, speak to her, I took. And soon, she was doing the same thing—looking forward to being with me,

"I couldn't hide my feeling from my father, but he didn't stand in my way. In fact, I'm sure he was eager to make more trips to the bayou because of my growing relationship with Gabrielle. I didn't realize then why he was encouraging it. I should have known something when he didn't appear upset the day I told him she was pregnant with my child."

"He went behind your back and made a deal with Grandpère Jack," I said.

"Yes, I didn't want such a thing to happen. I had already made plans to provide for Gabrielle and the child, and she was happy about it, but my father was obsessed with this idea, crazed by it."

He took a deep breath before continuing.

"He even went so far as to tell Daphne everything,"

"What did you do?" I asked.

"I didn't deny it. I confessed everything."

"Was she terribly upset?"

"She was upset, but Daphne is a woman of character, she's as they say, a very classy dame," he added with a smile. "She told me she wanted to bring up my child as her own, do what my father had asked. He had made her some promises, you see. But there was still Gabrielle to deal with, her feelings and desires to consider. I told Daphne what Gabrielle wanted and that despite the deal my father was making with your grandfather, Gabrielle would object."

"Grandmère Catherine told me how upset my mother was, but I never could understand why she let Grandpère Jack do it, why she gave up Gisselle."

"It wasn't Grandpère Jack who got her to go along. In the end," he said, "it was Daphne." He paused and turned to me. "I can see from the expression on your face that you didn't know that."

"No," I said.

"Perhaps your Grandmère Catherine didn't know either. Well, enough about all that. You know the rest anyway," he said quickly. "Would you like to walk through the French Quarter? There's Bourbon Street just ahead of us," he added, nodding.

"Yes."

We got out and he took my hand to stroll down to the corner. Almost as soon as we made the turn, we heard the sounds of music coming from the various clubs, bars, and restaurants, even this early in the day.

"The French Quarter is really the heart of the city," my father explained. "It never stops beating. It's not really French, you know. It's more Spanish. There were two disastrous fires here, one in 1788 and one in 1794, which destroyed most of the original French structures," he told me. I saw how much he loved talking about New Orleans and I wondered if I would ever come to admire this city as much as he did.

We walked on, past the scrolled colonnades and iron gates of the courtyards. I heard laughter above us and looked up to see men and women leaning over the embroidered iron patios outside their apartments, some calling down to people in the street. In an arched doorway, a black man played a guitar. He seemed to be playing for himself and not even notice the people who stopped by for a moment to listen.

"There is a great deal of history here," my father explained, pointing. "Jean Lafitte, the famous pirate, and his brother Pierre operated a clearinghouse for their contraband right there. Many a swashbuckling adventurer discussed launching an elaborate campaign in these courtyards."

I tried to take in everything: the restaurants, the coffee stalls, the souvenir shops, and antique stores. We walked until we reached Jackson Square and the St. Louis Cathedral.

"This is where early New Orleans welcomed heroes and had public meetings and celebrations," my father said. We paused to look at the bronze statue of Andrew Jackson on his horse before we entered the cathedral. I lit a candle for Grandmère Catherine and said a prayer. Then we left and strolled through the square, around the perimeter where artists sold their fresh works.

"Let's stop and have a cafe au lait and some beignets," my father said. I loved beignets, a donutlike pastry covered with powdered sugar.

While we ate and drank, we watched some of the artists sketching portraits of tourists.

"Do you know an art gallery called Dominique's?" I asked.

"Dominique's? Yes. It's not far from here, just a block or two over to the right. Why do you ask?"

"I have some of my paintings on display there," I said.

"What?" My father sat back, his mouth agape. "Your paintings on display?"

"Yes. One was sold. That's how I got my traveling money."

"I can't believe you," he said. "You're an artist and you've said nothing?"

I told him about my paintings and how Dominique had stopped by one day and had seen my work at Grandmère Catherine's and my roadside stall.

"We must go there immediately," he said. "I've never seen such modesty. Gisselle has something to learn from you."

Even I was overwhelmed when we arrived at the gallery. My picture of the heron rising out of the water was prominently on display in the front window. Dominique wasn't there. A pretty young lady was in charge and when my father explained who I was, she became very excited.

"How much is the picture in the window?" he asked.

"Five hundred and fifty dollars, monsieur," she told him.

Five hundred and fifty dollars! I thought. For something I had done? Without hesitation, he took out his wallet and plucked out the money.

"It's a wonderful picture," he declared, holding it out at arm's length. "But you've got to change the signature to Ruby Dumas. I want my family to claim your talent," he added, smiling. I wondered if he somehow sensed that this was a picture depicting what Grandmère Catherine told me was my mother's favorite swamp bird.

After it was wrapped, my father hurried me out excitedly. "Wait until Daphne sees this. You must continue with your artwork. I'll get you all the materials and we'll set up a room in the house to serve as your studio. I'll find you the best teacher in New Orleans for private lessons, too," he added. Overwhelmed, I could only trot along, my heart racing with excitement.

We put my picture into the car.

"I want to show you some of the museums, ride past one or two of our famous cemeteries, and then take you to lunch at my favorite restaurant on the dock. After all," he added with a laugh, "this is the deluxe tour."

It was a wonderful trip. We laughed a great deal and the restaurant he'd picked was wonderful. It had a glass dome so we could sit and watch the steamboats and barges arriving and going up the Mississippi.

While we ate, he asked me questions about my life in the bayou. I told him about the handicrafts and linens Grandmère Catherine and I used to make and sell. He asked me questions about school and then he asked me if I had ever had a boyfriend. I started to tell him about Paul and then stopped, for not only did it sadden me to talk about him, but I was ashamed to describe another terrible thing that had happened to my mother and another terrible thing Grandpère Jack had done because of it. My father sensed my sadness.

"I'm sure you'll have many more boyfriends," he said. "Once Gisselle introduces you to everyone at school."

"School?" I had forgotten about that for the moment.

"Of course. You've got to be registered in school first thing this week."

A shivering thought came. Were all the girls at this school like Gisselle? What would be expected of me?

"Now, now," my father said, patting my hand. "Don't get yourself nervous about it. I'm sure it will be fine. Well," he said, looking at his watch, "the ladies must all have risen by now. Let's head back. After all, I still have to explain you to Gisselle," he added.

He made it sound so simple, but as Grandmère Catherine would say, "Weaving a single fabric of falsehoods is more difficult than weaving a whole wardrobe of truth."

Daphne was sitting at an umbrella table on a cushioned iron chair on a patio in the garden where she had been served her late breakfast. Although she was still in her light blue silk robe and slippers, her face was made up and her hair was neatly brushed. It looked honey-colored in the shade. She looked like she belonged on the cover of the copy of Vogue she was reading. She put it down and turned as my father and I came out to greet her. He kissed her on the cheek.

"Should I say good morning or good afternoon?" he asked.

"For you two, it looks like it's definitely afternoon," she replied, her eyes on me. "Did you have a good time?"

"A wonderful time," I declared.

"That's nice. I see you bought a new painting, Pierre."

"Not just a new painting, Daphne, a new Ruby Dumas," he said, and gave me a wide, conspiratorial smile. Daphne's eyebrows rose.

"Pardon?"

My father unwrapped the picture and held it up. "Isn't it pretty?" he asked.

"Yes," she said in a noncommittal tone of voice. "But I still don't understand."

"You won't believe this, Daphne," he began, quickly sitting down across from her. He told her my story. As he related the tale, she gazed from him to me.

"That's quite remarkable," she said after he concluded.

"And you can see from the work and from the way she has been received at the gallery that she has a great deal of artistic talent, talent that must be developed."

"Yes," Daphne said, still sounding very controlled. My father didn't appear disappointed by her measured reaction, however. He seemed used to it. He went on to tell her the other things we had done. She sipped her coffee from a beautifully hand painted china cup and listened, her light blue eyes darkening more and more as his voice rose and fell with excitement.

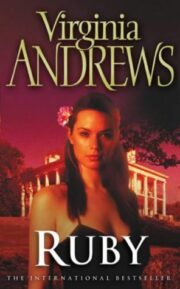

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.