"Oh, that's horrible," Paul said softly. Of all the boys I knew at school, Paul seemed the most sincere and the most mature, although, one of the shyest. He was certainly one of the handsomest with his cerulean blue eyes and thick, chatin hair, which was what the Cajuns called brown mixed with blond. "Good evening, Mrs. Landry," he said to Grandmère Catherine.

She flashed her gaze on him with that look of suspicion she had ever since the first time Paul had walked me home from school. Now that he was coming around more often, she was scrutinizing him even more closely, which was something I found embarrassing. Paul seemed a little amused, but a little afraid of her as well. Most folks believed in Grandmère's prophetic and mystical powers.

"Evening," she said slowly. "Might be a downpour yet tonight," she predicted. "You shouldn't be motoring about with that flimsy thing."

"Yes, ma'am," Paul said.

Grandmère Catherine shifted her eyes to me. "We got to finish the weavin' we started," she reminded me.

"Yes, Grandmère. I'll be right along."

She looked at Paul again and then went inside.

"Is your grandmother very upset about losing the Rodrigues baby?" he asked.

"She wasn't called to help deliver it," I replied, and I told him why she had been summoned and what we had done. He listened with interest and then shook his head.

"My father doesn't believe in any of that. He says superstitions and folklore are what keeps the Cajuns backward and makes other folks think we're ignorant. But I don't agree," he added quickly.

"Grandmère Catherine is far from ignorant," I added, not hiding my indignation. "It's ignorant not to take precautions against evil spirits and bad luck."

Paul nodded. "Did you . . . see anything?" he asked.

"I felt it fly by my face," I said, placing my hand on my cheek. "It touched me here. And then I thought I saw it leave."

Paul released a low whistle.

"You must have been very brave," he said.

"Only because I was with Grandmère Catherine," I confessed.

"I wish I had gotten here earlier and been with you . . . to make sure nothing bad happened to you," he added. I felt myself blush at his desire to protect me.

"I'm all right, but I'm glad it's over," I admitted. Paul laughed.

In the dim illumination of our galerie light, his face looked softer, his eyes even warmer. We hadn't done much more than hold hands and kiss a half-dozen times, only twice on the lips, but the memory of those kisses made my heart flutter now when I looked at him and stood so closely to him. The breeze gently brushed aside some strands of hair that had fallen over his forehead. Behind the house, the water from the swamps lapped against the shore and a night bird flapped its wings above us, invisible against the dark sky.

"I was disappointed when I came by and you weren't home," he said. "I was just about to leave when I saw the light of your lantern."

"I'm glad you waited," I replied, and his smile widened. "But I can't invite you in because Grandmère wants us to finish the blankets we'll put up for sale tomorrow. She thinks we'll be busy this weekend and she's usually right. She always remembers which weekends were busier than others the year before. No one has a better memory for those things," I added.

"I got to work in the cannery all day tomorrow, but maybe I can come by tomorrow night after dinner and we can walk to town to get a cup of crushed ice," Paul suggested.

"I'd like that," I said. Paul stepped closer to me and fixed his gaze on my face. We drank each other in for a moment before he worked up enough courage to say what he really had come to say. "What I really want to do is take you to the fais dodo next Saturday night," he declared quickly.

I had never been out on a real date before. Just the thought of it filled me with excitement. Most girls my age would be going to the fais dodo with their families and dance with boys they met there, but to be picked up and escorted and to dance only with Paul all night . . . that sent my mind reeling.

"I'll have to ask Grandmère Catherine," I said, quickly adding, "but I'd like that very much."

"Good. Well," he said, backing up toward his motor scooter, "I guess I better be going before that downpour comes." He didn't take his eyes off me as he stepped away and he caught his heel on a root. It sat him down firmly.

"Are you all right?" I cried, rushing to him. He laughed, embarrassed.

"I'm fine, except for a wet rear end," he added, and laughed. He reached up to take my hand and stand, and when he did, we were only inches apart. Slowly, a millimeter at a time, our lips drew closer and closer until they met. It was a short kiss, but a firmer and more confident one on both our parts. I had gone up on my toes to bring my lips to his and my breasts grazed his chest. The unexpected contact with the electricity of our kiss sent a wave of warm, pleasant excitement down my spine.

"Ruby," he said, bursting with emotion now. "You're the prettiest and nicest girl in the whole bayou."

"Oh, no, I'm not, Paul. I can't be. There are so many prettier girls, girls who have expensive clothes and expensive jewelry and—"

"I don't care if they have the biggest diamonds and dresses from Paris. Nothing could make them prettier than you," he blurted out. I knew he wouldn't have had the courage to say these things if we weren't standing in the shadows and I couldn't see him as clearly. I was sure his face was crimson.

"Ruby!" my grandmother called from a window. "I don't want to stay up all night finishing this."

"I'm coming, Grandmère. Good night, Paul," I said, and then I leaned forward to peck him on the lips once more before I turned and left him standing in the dark. I heard him start his motor scooter and drive off and then I hurried up to the grenier to help Grandmère Catherine.

For a long moment, she didn't speak. She worked and kept her eyes fixed on the loom. Then she shifted her gaze to me and pursed her lips the way she often did when she was thinking deeply.

"The Tate boy's been coming around to see you a great deal, lately, hasn't he?"

"Yes, Grandmère."

"And what do his parents think of that?" she asked, cutting right to the heart of things as always.

"I don't know, Grandmère," I said, looking down.

"I think you do, Ruby."

"Paul likes me and I like him," I said quickly. "What his parents think isn't important."

"He's grown a great deal this year; he's a man. And you're no longer a little girl, Ruby. You've grown, too. I see the way you two look at each other. I know that look too well and what it can lead to," she added.

"It won't lead to anything bad. Paul's the nicest boy in school," I insisted. She nodded but kept her dark eyes on me. "Stop making me feel naughty, Grandmère. I haven't done anything to make you ashamed of me."

"Not yet," she said, "but you got Landry in you and the blood has a way of corrupting. I seen it in your mother; I don't want to see it in you."

My chin began to quiver.

"I'm not saying these things to hurt you, child. I'm saying them to prevent your being hurt," she said, reaching out to put her hand over mine.

"Can't I love someone purely and nicely, Grandmère? Or am I cursed because of Grandpère Jack's blood in my veins? What about your blood? Won't it give me the wisdom I need to keep myself from getting in trouble?" I demanded. She shook her head and smiled.

"It didn't prevent me from getting in trouble, I'm afraid. I married him and lived with him once," she said, and then sighed. "But you might be right; you might be stronger and wiser in some ways. You're certainly a lot brighter than I was when I was your age, and far more talented. Why your drawings and paintings—"

"Oh, no, Grandmère, I'm—"

"Yes, you are, Ruby. You're talented. Someday someone will see that talent and offer you a lot of money for it," she prophesied. "I just don't want you to do anything to ruin your chance to get out of here, child, to rise above the swamp and the bayou."

"Is it so bad here, Grandmère?"

"It is for you, child."

"But why, Grandmère?"

"It just is," she said, and began her weaving again, again leaving me stranded in a sea of mystery.

"Paul has asked me to go with him to the fais dodo a week from Saturday. I want to go with him very much, Grandmère," I added.

"Will his parents let him do that?" she asked quickly. "I don't know. Paul thinks so, I guess. Can we invite him to dinner Sunday night, Grandmère? Can we?"

"I never turned anyone away from my dinner table," Grandmère said, "but don't plan on going to the dance. I know the Tate family and I don't want to see you hurt."

"Oh, I won't be, Grandmère," I said, nearly bouncing in my seat with excitement. "Then Paul can come to dinner?"

"I said I wouldn't throw him out," she replied.

"Oh, Grandmère, thank you. Thank you." I threw my arms around her. She shook her head.

"If we go on like this, we'll be working all night, Ruby," she said, but kissed my cheek. "My little Ruby, my darling girl, growing into a woman so quickly I better not blink or I'll miss it," she said. We hugged again and then went back to work, my hands moving with a new energy, my heart filled with a new joy, despite Grandmère Catherine's ominous warnings.

2

No Landrys Allowed

A blend of wonderful aromas rose from the kitchen and seeped into my room to snap my eyes open and start my stomach churning in anticipation. I could smell the rich, black Cajun coffee percolating on the stove and the mixture of shrimp and chicken gumbo Grandmère Catherine was preparing in her black, cast iron cooking pots to sell at our roadside stall. I sat up and inhaled the delicious smells.

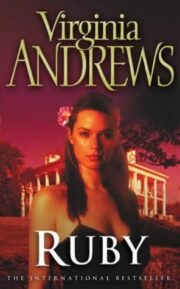

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.