"No," I said. "They don't even know I exist," I added.

The bus shot forward, its headlights slicking through the night, carrying me onward toward the future that awaited, a future just as dark and mysterious and as frightening as the unlit highway.

Book Two

10

An Unexpected Friend

Annie Gray was so excited about arriving in New Orleans during the Mardi Gras, she talked incessantly during the remainder of the trip. I sat with my knees together, my hands nervously twisting on my lap, but I was grateful for the conversation. Listening to her descriptions of previous Mardi Gras celebrations she had attended, I had little time to feel sorry for myself and worry about what would happen to me the moment I stepped off the bus. For the time being at least, I could ignore the troubled thoughts crowded into the darkest corners of my brain.

Annie came from New Iberia, but she had been to New Orleans at least a half-dozen times to visit her aunt, who she said was a cabaret singer in a famous nightclub in the French Quarter. Annie said she was going to live with her aunt in New Orleans from now on.

"I'm going to be a singer, too," she bragged. "My aunt is getting me my first audition in a nightclub on Bourbon Street. You know about the French Quarter, don'tcha, honey?" she asked.

"I know it's the oldest section of the city and there is a lot of music, and people have parties there all the time," I told her.

"That's right, honey, and it has the best restaurants and many nice shops and loads and loads of antique and art galleries."

"Art galleries?"

"Uh-huh."

"Did you ever hear of Dominique's?"

She shrugged.

"I wouldn't know one from the other. Why?"

"I have some of my artwork displayed there," I said proudly.

"Really? Well, ain't that somethin'? You're an artist." She looked impressed. "And you say you ain't ever been to New Orleans before?"

I shook my head.

"Oh," she squealed, and squeezed my hand. "You're in for a bundle of fun. You've got to tell me where you'll be and I'll send you an invitation to come hear me sing as soon as I get hired, okay?"

"I don't know where I'll be yet," I had to confess. That slowed down her flood of excitement. She pulled herself back in her seat and scrutinized me with a curious smile on her face.

"What do you mean? I thought you said you're going to visit relatives," she said.

"I am . . . I . . . just don't know their address." I allowed my eyes to meet hers briefly before they fled to stare almost blindly at the passing scenery, which right now was a blur of dark silhouettes and an occasional lit window of a solitary house.

"Well, honey, New Orleans is a bit bigger than downtown Houma," she said, laughing. "You got their phone number at least, don'tcha?"

I turned back and shook my head. Numbness tingled in my fingertips, perhaps because I had my fingers locked so tightly together.

Her smile wilted and she narrowed her turquoise eyes suspiciously as her gaze shifted to my small bag and then back to me. Then she nodded to herself and sat forward, convinced she knew it all.

"You're runnin' away from home, ain'tcha?" she asked. I bit down on my lower lip, but I couldn't stop my eyes from tearing over. I nodded.

"Why?" she asked quickly. "You can tell Annie Gray, honey. Annie Gray can keep a secret better than a bank safe."

I swallowed my tears and vanquished my throat lump so I could tell her about Grandmère Catherine, her death, Grandpère Jack's moving in and his quickly arranging for my marriage to Buster. She listened quietly, her eyes sympathetic until I finished. Then they blazed furiously.

"That old monster," she said. "He be Papa La Bas," she muttered.

"Who?"

"The devil himself," she declared. "You got anything that belongs to him on you?"

"No," I replied. "Why?"

"Fixin'," she said angrily. "I'd cast a spell on him for you. My great-Grandmère, she was brought here a slave, but she was a mamaloa." Voodoo queen, and she hand me down lots of secrets," she whispered, her eyes wide, her face close to mine. "Ya, ye, ye Ii konin tou, gris-gris," she chanted. My heart began to pound.

"What's that mean?"

"Part of a voodoo prayer. If I had a snip of your Grandpère's hair, a piece of his clothing, even an old sock . . . he never be bothering you again," she assured me, her head bobbing.

"That's all right. I'll be fine now," I said, my voice no more than a whisper either.

She stared at me a moment. The white part of her eyes looked brighter, almost as if there were two tiny fires behind each orb. Finally, she nodded again, patted my hand reassuringly and sat back.

"You be all right, you just don't lose that black cat bone I gave you," she told me.

"Thank you." I let out a breath. The bus bounced and turned on the highway. Ahead of us, the road became brighter as we approached more lighted and populated areas en route to the city that now loomed before me like a dream.

"I tell you what you do when we arrive," Annie said. "You go right to the telephone booth and look up your relatives in the phone book. Besides their telephone number, their address will be there. What's their name?"

"Dumas," I said.

"Dumas. Oh, honey, there's a hundred Dumas in the book, if there's one. Know any first names?"

"Pierre Dumas."

"Probably at least a dozen or so of them," she said, shaking her head. "He got a middle initial?"

"I don't know," I said.

She thought a moment.

"What else do you know about your relatives, honey?"

"Just that they live in a big house, a mansion," I said. Her eyes brightened again.

"Oh. Maybe the Garden District then. You don't know what he does for a living?"

I shook my head. Her eyes turned suspicious as one of her eyebrows lifted quizzically.

"Who's Pierre Dumas? Your cousin? Your uncle?"

"No. My father," I said. Her mouth gaped open and her eyes widened with surprise.

"Your father? And he never set eyes on you before?"

I shook my head. I didn't want to go through the whole story, and thankfully, she didn't ask for details. She simply crossed herself and muttered something before nodding.

"I'll look in the phone book with you. My Grandmère told me, I have a mama's vision and can see my way through the dark and find the light. I'll help you," she added, patting my hand. "Only, one thing must be to make it work," she added.

"What's that?"

"You've got to give me a token, something valuable to open the doors. Oh, it ain't for me," she added quickly. "It's a gift for the saints to thank them for help in the success of your gris-gris. I'll drop it by the church. Whatcha got?"

"I don't have anything valuable," I said.

"You got any money on you?" she asked.

"A little money I've earned selling my artwork," I told her.

"Good," she said. "You give me a ten dollar bill at the phone booth and that will give me the power. You lucky you found me, honey. Otherwise, you'd be wanderin' around this city all night and all day. Must be meant to be. Must be I be your good gris-gris."

And with that she laughed again and again began describing how wonderful her new life in New Orleans was going to be once her aunt got her the opportunity to sing.

When I first saw the skyline of the city, I was glad I had found Annie Gray. There were so many buildings and there were so many lights, I felt as if I had fallen into a star laden sky. The traffic and people, the maze of streets was over-whelming and frightening. Everywhere I looked out the bus window, I saw crowds of revelers marching through the streets, all of them dressed in bright costumes, wearing masks and hats with bright feathers and carrying colorful paper umbrellas. Instead of masks, some had their faces made up to look like clowns, even the women. People were playing trumpets and trombones, flutes and drums. The bus driver had to slow down and wait for the crowds to cross at almost every corner before finally pulling into the bus station. As soon as he did so, our bus was surrounded by partygoers and musicians greeting the arriving passengers. Some were given masks, some had ropes of plastic jewels cast over their heads and some were given paper umbrellas. It seemed if you weren't celebrating Mardi Gras, you weren't welcome in New Orleans.

"Hurry," Annie told me as we started down the aisle. As soon as I stepped down, someone grabbed my left hand, shoved a paper umbrella into my right, and pulled me into the parade of brightly dressed people so that I was forced to march around the bus with them. Annie laughed and threw her hands up as she started to dance and swing herself in behind me. We marched around as the bus driver unloaded the luggage. When Annie saw hers, she pulled me out of the line and I followed her into the station. People were dancing everywhere, and everywhere I looked, there were pockets of musicians playing Dixieland Jazz.

"There's a phone booth," she said, pointing. We hurried to it. Annie opened the fat telephone book. I had never realized how many people lived in New Orleans. "Dumas, Dumas," she chanted as she ran her finger down the page. "Okay, here be the list. Quickly," she said, turning back to me. "Fold the ten dollar bill as tightly as you can. Go on."

I did what she asked. She opened her purse and kept her eyes closed.

"Just drop it in here," she said. I did so and she opened her eyes slowly and then turned to the phone book again. She did look like someone who had fallen into a trance. I heard her mumble some gibberish and then she put her long right forefinger on the page and ran it down slowly. Suddenly, she stopped. Her whole body shuddered and she closed and then opened her eyes. "It's him!" she declared. She leaned closer and nodded. "He does live in the Garden District, big house, rich." She tore off a corner of the page and wrote the address on it. It was on St. Charles Avenue.

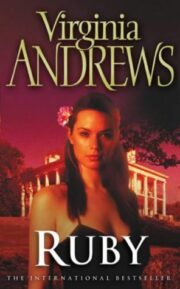

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.