All was quiet. The butane lantern below flickered weakly, casting a dim glow and making the distorted silhouettes dance over the stairs and the walls. Was Grandpère asleep in Grandmère Catherine's room? I decided not to look, but instead, I slipped out of my bedroom and tiptoed to the stairs. No matter how softly I walked, however, the wooden floors creaked. It was as if the house wanted to betray me. I paused, listened, and then continued down the stairs. When I reached the bottom, I waited and listened. Then I went forward and discovered Grandpère Jack sprawled on the floor by the front door. He was snoring loudly.

I didn't want to risk stepping over him and going out the front, so I turned to the back, but I stopped halfway to the kitchen. I had to do one last thing, take one last look at the picture I had painted of Grandmère Catherine that hung on the wall in the parlor. I walked back softly and paused in the doorway. Moonlight pouring through the uncovered window illuminated the portrait, and for a moment it seemed to me that Grandmère was smiling, that her eyes were full of happiness because I was keeping to my promise.

"Good-bye, Grandmère," I whispered. "Someday, I'll return to the bayou and I'll take your picture back with me to wherever I live."

How I wished I could hug her and kiss her one more time. I closed my eyes and tried to remember the last time I had, but Grandpère Jack groaned and turned over on the floor. I didn't move a muscle. His eyes opened and closed. If he had seen me, he must have thought it was a dream, for he didn't wake up. Not wasting another second, I turned away and walked quickly but quietly through the kitchen and out the back door. Then, I hurried around the corner of the house and headed for the front.

When I reached the road, I stopped and looked back. Something sweet and sour was in my throat. Despite all that had happened and all that would, it hurt me to leave this simple house that had known my first steps. Within those plain old walls Grandmère Catherine and I had made many a meal together, sung together, and laughed together. On that galerie, she had rocked and told me story after story about her own youthful days. Upstairs in that bedroom, she had nursed me through my childhood illnesses and told me the bedtime stories that made it easier to close my eyes and sleep contentedly, always feeling safe and secure in the cocoon of promises she wove with her soft voice and soft, loving eyes. Sitting by my bedroom window on hot summer nights, I had fantasized my future, seen my prince come, envisioned my jeweled wedding with the gold dust in the spiderwebs and the music.

Oh, it was more than an old swamp house I was leaving. It was my entire past, my years of growing and developing, my feelings of joy and feelings of sadness, my melancholy and my ecstasy, my laughter and my tears. How hard it was even now, even after all this, to turn away from it and let dark night shut the door of blackness behind me.

And what of the swamp itself? Could I really tear myself away from the flowers and the birds, from the fish and even the alligators who peered at me with interest? In the moonlight on a limb of a sycamore, sat a marsh hawk, his silhouette dark and proud against the white glow. He opened his wings and held them as if he were saying good-bye for all the swamp animals and birds and fish. And then he closed his wings and I turned and hurried off, the hawk's silhouette still lingering on the surface of my vision.

On the way into Houma, I passed many of the houses of people I knew, people I thought I might never see again. I almost paused at Mrs. Thibodeau's to say good-bye. She and Mrs. Livaudis were such special friends to me and my Grandmère, but I was afraid she would try to talk me out of leaving and try to talk me into staying either with her or Mrs. Livaudis. I pledged to myself that someday, when I was finally settled, I would write to both of them.

Few places were still open in town when I arrived. I went directly to the bus station and bought a one-way ticket to New Orleans. I had nearly an hour to wait and spent most of it on a bench in the shadows, fearful that someone would spot me and either try to stop me or tell Grandpère before I left. Twice, I thought about calling Paul, but I was afraid to talk to him. If I told him what Grandpère Jack had done, he was sure to lose his temper and do something terrible. I decided to write him a good-bye note instead. I bought an envelope and a stamp in the station and dug out a piece of paper from my pocketbook.

Dear Paul,

It would take too long to explain to you why I am leaving Houma without saying good-bye. I think the main reason though is I know how much it would break my heart to look at you and then leave. It hurts so much even writing this note. Let me just tell you that more things happened in the past than I revealed that day, and these events are taking me away from Houma to find my real father and my other life. There is nothing I would want more than to spend the rest of my life at your side. It seems like such a cruel joke for Nature to let us fall in love the way we did and then surprise us with the ugly truth. But I know now that if I didn't leave, you would not give up and you would make it painful for both of us.

Remember me as I was before we learned the truth, and I'll remember you the same way. Maybe you're right maybe we'll never love anyone else as much as we love each other, but we have to try. I will think of you often, and I will imagine you in your beautiful plantation.

Love always, Ruby

I posted the letter in the mailbox in front of the bus station and then I sat down and choked back my tears and waited. Finally, the bus arrived. It had come from St. Martinville and had made stops and picked up passengers at New Iberia, Franklin, and Morgan City before arriving at Houma, so the bus was nearly filled when I stepped up and gave the driver my ticket. I made my way toward the rear and saw an empty seat on the right next to a pretty caramel skinned woman with black hair and turquoise eyes. She smiled when I sat down, revealing milk white teeth. She wore a bright pink and blue peasant skirt with black sandals, a pink halter, and she had rings and rings of different bracelets on both her arms. She had her hair tied with a white kerchief, a tignon with seven knots whose points all stuck straight up.

"Hello," she said. "Going to the wet grave, too?"

"Wet grave?" I sat down beside her.

"New Orleans, honey. That's what my Grandmère called it because you can't bury anyone in the ground. Too much water."

"Really?"

"That's true. Everyone's buried in tombs, vaults, ovens above the ground. You didn't know that?" she asked, holding her smile. I shook my head. "First time to New Orleans then, huh?"

"Yes, it is."

"You picked the best time to visit, you know," she said. I saw how bright her eyes were, how full of excitement she was.

"Why?"

"Why? Why, honey, it's Mardi Gras."

"Oh . . . no," I said, thinking to myself that it was the worst time to go, not the best. I had read and heard about New Orleans at Mardi Gras. I should have realized that was why she was all dressed up. The whole city would be festive. It wasn't the best time to arrive on my real father's doorstep.

"You act like you just stepped out of the swamp, honey."

I took a deep breath and nodded. She laughed.

"My name's Annie Gray," she said, offering her slim, smooth hand. I took it and shook. She had pretty rings on all her fingers, but one ring, the one on her pinky, looked like it was made out of bone and shaped like a tiny skull.

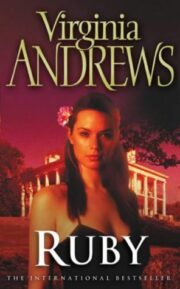

"I'm Ruby, Ruby Landry."

"Pleased to meet you. You got relatives in New Orleans?" she asked.

"Yes," I said. "But I haven't seen them . . . ever."

"Oh, ain't that somethin'?"

The bus driver closed the door and started the bus away from the station. My heart began to race as I saw us drive by stores and houses I had known all my life. We passed the church and then the school, moving over the road I had walked almost every day of my life. Then we paused at an intersection and the bus turned in the direction of New Orleans. I had seen the road sign many times, and many times dreamt of following it. Now I was. In moments we were flying down the highway and Houma was falling farther and farther behind. I couldn't help but look back.

"Don't look back," Annie Gray said quickly.

"What? Why not?"

"Bad luck," she replied.

I spun around to face forward.

"What?"

"Bad luck. Quick, cross yourself three times," she prescribed. I saw she was serious and so I did it.

"I don't need any more of that," I said. That made her laugh. She leaned forward and picked up her cloth bag. Then she dug into it and came up with something to place in my hand. I stared at it.

"What's this?" I asked.

"Piece of neck bone from a black cat. It's gris-gris," she said. Seeing I was still confused, she added, "a magical charm to bring you good luck. My Grandmère gave it to me. Voodoo," she added in a whisper.

"Oh. Well, I don't want to take your good luck piece," I said, handing it back. She shook her head.

"Bad luck for me to take it back now and worse luck for you to give it," she said. "I got plenty more, honey. Don't worry about that. Go on," she said, forcing me to wrap my fingers around the cat bone. "Put it away, but carry it with you all the time."

"Thank you," I said, and slipped it into my bag.

"I bet these relatives of yours are excited about seeing you, huh?"

"No," I said.

She tilted her head and smiled with confusion. "No? Don't they know you're comin'?"

I looked at her for a moment and then I looked forward again, straightening myself up in the seat.

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.