"I'm talking to you, child."

"I heard you, Grandpère," I said. I wiped my tears away with the back of my hand and turned around. "But I told you, I'm not ready to marry anyone and I'm still in school. I want to be an artist anyway," I said.

"Hell, you can be an artist. Buster here would buy you all the paint and brushes you'd need for a hundred years, wouldn't ya, Buster?"

"Two hundred," he said, and laughed.

"See?"

"Grandpère, don't do this," I pleaded. "You're embarrassing me."

"Huh? You're too old for that kind of thing, Ruby. Besides, I can't be around here watchin' over you all day now, can I? Your Grandmère's gone; it's time for you to grow up."

"She sure looks good and grow'd up to me," Buster said and wiped his thick tongue over the side of his mouth to scoop in a piece of crawfish that had attached itself to the grizzle of his unshaven face.

"Hear that, Ruby?"

"I don't want to hear that. I don't want to talk about it. I'm not marrying anyone right now," I cried. I backed away from the sink and from them. "And especially not Buster," I added, and charged out of the kitchen and up the stairs.

"Ruby!" Grandpère called.

I paused at the top of the stairway to catch my breath and heard Buster complain.

"So much for your easy arrangements, Jack. You brought me here, got me to buy you this case of beer and she ain't the obedient little lady you promised."

"She will be," Grandpère Jack told him. "I'll see to that."

"Maybe. You're just lucky I like a girl who has some spirit. It's like breaking a wild horse," Buster said. Grandpère Jack laughed. "Tell you what," Buster said. "I'll up what I was going to give you by another five hundred if I can test the merchandise first."

"What'dya mean?" Grandpère asked.

"I don't got to spell it out, do I, Jack? You're just playin' dumb to get me to raise the ante. All right, I'll admit she's special. I'll give you one thousand tomorrow for a night alone with her and then the rest on our wedding day. A woman should be broken in first anyway and I might as well break in my wife myself."

"A thousand dollars!"

"You got it. What'dya say?"

I held my breath. Tell him to go straight to hell, Grandpère, I whispered.

"Deal," Grandpère Jack said instead. I could see them shaking hands and then opening another bottle of beer.

I hurried into my room and closed the door. If ever I needed proof that all the stories about Grandpère Jack were true, I just got it, I thought. No matter how drunk he got, no matter how many gambling debts he mounted, he should have some feeling for his own flesh and blood. I was seeing firsthand the sort of ugly and selfish animal Grandpère had become in Grandmère Catherine's eyes. Why didn't I have the courage to obey my promise to her immediately? I thought. Why do I always look for the best in people, even when there's not a hint of any there? All my lessons are to be learned the hard way, I concluded.

Less than an hour or so later, I heard Grandpère come up the stairs. He didn't knock on my door; he shoved it open and stood there glaring in at me. He was fuming so fiercely it looked like smoke might pour out of his red ears.

"Buster's gone," he said. "He lost his appetite over your behavior."

"Good."

"You ain't gonna be like this, Ruby," he said, pointing his finger at me. "Your Grandmère Catherine spoiled you, probably fillin' you with all sorts of dreams about your artwork and tellin' you you're goin' to be some sort of fancy city lady, but you're just another Cajun girl, prettier than most, admit; but still a Cajun girl who should thank her lucky stars a man as rich as Buster Trahaw's taken interest in her.

"Now, instead of being grateful, what do you do? You make me look like a fool," he said.

"You are a fool, Grandpère," I retorted. His face turned crimson. I sat up in my bed. "But worse, you're a selfish man who would sell his own flesh and blood just to keep himself in whiskey and gambling."

"You apologize for that, Ruby. You hear."

"I'm not apologizing, Grandpère. It's you who have years of apologizing to do. You're the one who has to apologize for blackmailing Mr. Tate and selling Paul to him."

"What? Who told you that?"

"You're the one who has to apologize for arranging the sale of my sister to some Creoles in New Orleans. You broke my mother's heart and Grandmère Catherine's, too," I accused. He stood there sputtering for a moment.

"That's a lie. All of it, a lie. I did what was necessary to do to save the family name and made a little on the side to help us out," he protested. "Catherine just worked you up against me by telling you otherwise and—"

"Just like you're selling me to Buster Trahaw, making a deal with him to come up here tomorrow night," I said, crying. "You, my grandfather, someone who should be looking after me, protecting me . . . you, you're nothing more than . . . than the swamp animal Grandmère said you were," I shouted.

He seemed to swell up, his shoulders rising so he reached his full height, his crimson face turning darker until his complexion was almost the color of my hair, his eyes so full of anger, they seemed luminous.

"I see these busybodies have filled you with defiance and turned you against me. Well, I'm doin' what's best for you by convincing a man as rich and prosperous as Buster to take interest in you. If I make something on the side, too, you should be happy for me."

"I'm not and I won't marry Buster Trahaw," I cried.

"Yes, you will," Grandpère said. "And you'll thank me for it, too," he predicted. Then he turned and left my room, pounding down the stairs.

A short while later, I heard him turn on the radio and then I heard some beer bottles clank and shatter. He was having one of his tantrums. I decided to wait in my room until he fell into his stupor. Afterward, I would leave.

I started to pack a small bag, being as selective as I could about what I would take because I knew I had to travel light. I had my art money hidden under the mattress, but I decided not to take it out until just before I was ready to leave. Of course, I would take the photographs of my mother and the one photograph of my real father and my sister. As I pondered what else to bring, I heard Grandpère's ranting grow more intense. Something else shattered and a chair was smashed. Shortly afterward, I heard something rattle and then I heard his heavy, unsure steps on the stairs.

I cowered back in my bed, my heart thumping. My door was thrown open again and he stood there, gazing in at me, the flames of anger in his eyes fanned by the whiskey and beer he had consumed. He looked around and saw my little bag in the corner.

"Goin' somewheres, are ya?" he asked, smiling. I shook my head. "Thought you might do that . . . thought you might leave me lookin' the fool."

"Grandpère, please," I began but he stepped forward with surprising agility and seized my left ankle. I screamed as he wrapped what looked like a bicycle chain around it and then ran the chain down and around the leg of the bed. I heard him snap on a lock before he stood up.

"There," he said. "That should help bring you to your senses."

"Grandpère . . . unlock me!"

He turned away.

"You'll be thankin' me," he muttered. "Thankin' me." He stumbled out of the door and left me, terrified, crying hysterically.

"Grandpère!" I screamed. My throat ached with the effort and the tears. When I stopped and listened, it sounded as if he had tripped and fallen down the stairs. I heard him curse and then I heard more banging and more furniture shattering. After a while it grew quiet.

Stunned by what he had done, I could only lie there and sob until my chest felt as if it were filled with stones. Grandpère was worse than a swamp animal; he was a monster, for swamp animals would never be as cruel to their own kind, I thought. And there was just so much to blame on the whiskey and beer.

Out of exhaustion and fear, I fell asleep, eagerly accepting the slumber as a form of escape from the horror I had never dreamed.

When I awoke, I felt as if I had slept for hours, but not even two had passed. I had no chance to think that what had happened was just a bad nightmare either, for the moment I moved my leg, I heard the chain rattle. I sat up quickly and tried to slide it off my ankle, but the harder I tugged, the deeper and sharper it cut into my skin. I moaned and buried my face in my hands for a moment. If Grandpère left me chained up like this all day . . . if I were like this when Buster Trahaw returned, I would be defenseless, helpless.

A cold, electric chill cut through my heart. I couldn't remember ever feeling such terror. I listened. All was quiet in the house. Even the breeze barely made the walls creak. It was as if time stood still, as if I were trapped in the eye of a great storm that was about to break over my head. I took a deep breath and tried to calm myself down enough to think clearly. Then I studied the chain and followed the line of it to the leg of the bed.

A surge of relief came over me when I realized that Grandpère Jack in his drunken state had merely wound and locked the chain around the leg, forgetting that I could lift the bed and slide the chain down. I twisted my body until I had my other leg off the bed and then lowered myself awkwardly, painfully, until I was far enough to get the leverage I needed. It took all the strength I could muster, but the bed lifted and I began to nudge the chain down until it fell off the bottom of the leg. I worked the chain around until I unraveled it from my ankle, which was plenty red and sore. Carefully, as quietly as I could, I lay the chain on the floor. Then I picked up my little bag of clothes and precious items, dug my money out from under the mattress, and went to the bedroom door. I opened it a crack and listened.

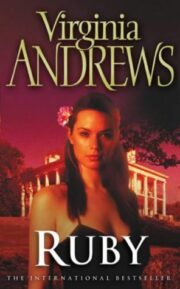

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.