I shook my head. "I've got to start on dinner for Grandpère Jack, Paul," I told him, retreating a step.

"You've got plenty of time and you know he'll either be late or not show up until he's too drunk to care," he replied. "Come on. Please," he begged.

"Paul, I don't want anything to happen like it did the other day," I said.

"Nothing will happen. I won't come near you. I just want to show you something. I'll bring you right back," he promised. He held up his hand to take an oath. "I swear."

"You won't come near me and you'll bring me right back?"

"Absolutely," he said, and leaned forward to take my hand as I hopped over the shale and stepped up and into the motorboat. "Just sit back," he said, starting the engine again. He spun the boat around sharply and accelerated with the confidence of an old Cajun swamp fisherman. Even so, I screamed. The best fisherman often ran into gators or sandbars. Paul laughed and slowed down.

"Where are you taking me, Paul Tate?" He steered us through the shadows cast by an overhang of willow trees, deeper and deeper into the swamp before heading southwest in the direction of his father's cannery. Off in the distance I could see thunderheads over the Gulf. "I don't want to get caught in any storms," I complained.

"My, you can be a nag," Paul said, smiling. He wove us through a narrow passage and then headed for a field, cutting his engine as we drew closer and closer. Finally, he turned it off to let the boat drift.

"Where are we?"

"My land," he replied. "And I don't mean my father's land. My land," he emphasized.

"Your land?"

"Yep," he said proudly and leaned back against the side of the boat. "All that you see—sixty acres actually. It's mine, my inheritance." He gestured broadly at the field.

"I never knew that," I said, gazing over what looked like prime land in the bayou.

"My grandfather Tate left it to me. It's held in trust, but it will be mine as soon as I turn eighteen, but that isn't the best of it," he said, smiling.

"Well, what is then?" I asked. "Stop grinning like a Cheshire cat and tell me what this is all about, Paul Tate."

"Better than tell you, I'll show you," he said, and took up the oar to paddle the boat softly through some marsh grass and into a dark, shadowy area. I stared ahead and soon saw the bubbles in the water.

"What's that?"

"Gas bubbles," he said in a whisper. "You know what it means?"

I shook my head.

"It means oil is under here. Oil and it's on my land. I'm going to be rich, Ruby, very rich," he said.

"Oh, Paul, that's wonderful."

"Not if you're not with me to share it," he said quickly. "I brought you here because I wanted you to see my dreams. I'm going to build a great house on my land. It will be a great plantation, your plantation, Ruby."

"Paul, how can we even think such a thing? Please," I said. "Stop tormenting yourself and me, too."

"We can think of such a thing, don't you see? The oil is the answer. Money and power will make it all possible. I'll buy Grandpère Jack's blessings and silence. We'll be the most respected, prosperous couple in the bayou, and our family—"

"We can't have children, Paul."

"We'll adopt, maybe even secretly, with your doing the same thing my mother did—pretending the baby is yours, and then—"

"But, Paul, we'll be living the same sort of lies, the same deceits, and they will haunt us forever," I said, shaking my head.

"Not if we don't let them, not if we permit ourselves to love and cherish each other the way we always dreamed we would," he insisted.

I turned away from him and watched a bullfrog jump off a log. It created a small circle of ripples that quickly disappeared. In a corner of the pond, I saw bream feeding on insects among the cattails and lily pads. The wind began to pick up and the Spanish moss swayed along with the twisted limbs of the cypress. A flock of geese passed overhead and disappeared over the tops of trees as if they had flown into the clouds.

"It's beautiful here, Paul. And I wish it could be our home someday, but it can't and it's just cruel to bring me here and tell me these things," I said, chastising him softly.

"But, Ruby—"

"Don't you think I wish it could be, wish it as much as you do?" I said, spinning around on him. My eyes were burning with tears of anger and frustration. "The same feelings that are tearing you apart are tearing me, but we're just prolonging the pain by fantasizing like this."

"It's not a fantasy; it's a plan," he said firmly. "I've been thinking about it all weekend. After I'm eighteen . . ."

I shook my head.

"Take me back, Paul. Please," I said. He stared at me a moment.

"Will you at least think about it?" he pleaded. "Will you?"

"Yes," I said, because I saw it was the key that would open the door and let us out of this room of misery.

"Good." He started the engine and drove us back to the dock at my house.

"I'll see you at school tomorrow," he said after he helped me out of the boat. "We'll talk about this every day, think it out clearly, together, okay?"

"Okay, Paul," I said, confident that one morning he would awaken and realize that his plan was a fantasy not meant to become a reality.

"Ruby," he cried as I started toward the house. I turned. "I can't help loving you," he said. "Don't hate me for it."

I bit down on my lower lip and nodded. My heart was soaked in the tears that had fallen behind my eyes. I watched him drive off and waited until his motorboat disappeared into the bayou. Then I took a deep breath and entered the house.

The roar of Grandpère's laughter greeted me and was immediately followed by the laughter of a stranger. I walked into the kitchen slowly to discover Grandpère Jack sitting at the table. He and a man I recognized as Buster Trahaw, the son of a rich sugar plantation owner, sat hunched over a large bowl of crawfish. There were at least a half-dozen or so empty bottles of beer on the table that they had drawn out of a case on the floor at their feet.

Buster Trahaw was a man in his mid-thirties, tall and stout with a circle of fat around his stomach and sides that made it look as if he wore an inner tube under his shirt. All of the features of his plain face were distorted by the bloat. He had a thick nose with wide nostrils, heavy jowls, a round chin, and a soft mouth with thick purple lips. His forehead protruded over his cavernous dark eyes and his large earlobes leaned away from his head so that from behind, he looked like a big bat. Right now, his dull brown hair was matted down with sweat, the strands sticking to the top of his forehead.

As soon as I stepped into the room, his smile widened, showing a mouthful of large teeth. Pieces of crawfish were visible between the gaps and his thick pink tongue was covered with the meat as well. He brought the neck of a beer bottle to his lips and drew on it so hard, his cheeks folded in and out like the bellows of an accordion. Grandpère Jack spun around in his chair when he caught Buster's smile.

"Well, where you been, girl?" Grandpère demanded.

"I went for a walk," I said.

"Me and Buster been here waitin' on you," Grandpère said. "Buster's our guest for dinner tonight," he said. I nodded and went to the icebox. "Can't you say hello to him?"

"Hello," I said, and turned back to the icebox. "Did you bring any fish or duck or anything for the gumbo, Grandpère?" I asked without looking at him. I took out some vegetables.

"There's a pile of shrimp in the sink just waitin' to be shelled," he replied. "She's one helluva cook, Buster. I'd match her gumbo, her jambalaya, and étouffée with any in the bayou," he bragged.

"Don't say?" Buster replied.

"You'll soon see. Yes, sir, you will. And look how nicely she keeps the house, even with a hog like me liven' in it," Grandpère added.

I turned and gazed at him suspiciously, my eyes no more than dark slits. He sounded like he was doing a lot more than bragging about his granddaughter; he sounded like someone advertising something he wanted to sell. My suspicious gaze didn't shake him. "Buster here knows about you, Ruby," he said. "He told me he's seen you walking along the road or tending to the stall or in town many times. Ain't that right, Buster?"

"Yes, sir, it is. And I always liked what I saw," he said. "You keep yourself nice and pretty, Ruby," he said.

"Thank you," I said, and turned away, my heart beginning to pound.

"I told Buster here that my granddaughter, she's gettin' to the point when she should think of settlin' down and havin' a place of her own, her own kitchen, her own flock to tend," Grandpère Jack continued. I started to shell the shrimp, "Most women in the bayou end up no better than they were to start, but Buster here, he's got one of the best plantations going."

"One of the biggest and best," Buster added.

"I'm still going to school, Grandpère," I said. I kept my back to him and Buster so neither would see the fear in my face or the tears that were starting to escape my lids and trickle down my cheeks.

"Aw, school ain't important anymore, not at your age. You've already gone longer than I did," Grandpère said. "And I bet longer than you did, huh, Buster?"

"That's for sure," Buster said, then laughed.

"All Buster had to learn was how to count the money comin' in, ain't that right, Buster?"

The two of them laughed.

"Buster's father is a sick man; his days are numbered and Buster's going to inherit the whole thing, ain't you, Buster?"

"That's true and I deserve it, too," Buster said.

"Hear that, Ruby?" Grandpère said. I didn't respond.

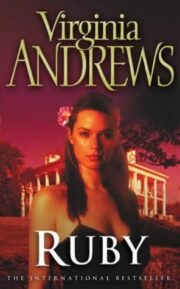

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.