No one had seen Grandpère Jack for some time so Thaddeus Bute poled a pirogue out to his shack to give him the dreadful news. He returned without him and mumbled something to the mourners that made people shake their heads and gaze my way with pity. Toward supper Grandpère Jack finally arrived, as usual, resembling someone who had been wallowing in mud. He wore what must have been his best pair of trousers and shirt, but the trousers had holes in the knees and his shirt looked like he had to beat it on a rock in order to soften it enough to slip his arms through the sleeves and button it, wherever there were buttons, that is. Of course, his boots were caked with grime and blades of marsh grass.

He had taken no time to brush down his wild white hair or trim his beard even though he must have known there would be loads of people here. Thick little puffs of hair grew out of his ears and nose. His bushy eyebrows curved up and to the side on his leather tan face, the deeper wrinkles looking like they had a bed of dirt glued there for months. The acrid odors of stale whiskey, swamp earth, fish, and tobacco seemed to arrive at the house long moments before he did. I smiled to myself thinking how Grandmère Catherine would be screaming at him to keep his distance.

But she wasn't going to be screaming at him anymore. She was laid out in the sitting room, her face never so peaceful and still. I sat off to the right of the coffin, my hands folded in my lap, still quite dazed by the reality of what was happening, still disbelieving, hoping it was all a terrible nightmare that would soon end.

The quiet chatter that had begun earlier came to an abrupt pause when Grandpère Jack arrived. As soon as he strode into the house, the people gathered at the doorways parted and stepped back as if they were terrified he might touch them with his polluted hands. None of the men offered theirs to him, nor did he seek any handshakes. Women grimaced after a whiff of him. His eyes shifted quickly from one face to another and then he stepped into the sitting room and froze for a moment at the sight of Grandmère Catherine laid out in her coffin.

He looked at me sharply and then fixed his eyes on Father Rush. For a few moments, it seemed Grandpère Jack didn't trust what his own eyes were telling him or what people were doing here. It looked like the words were on the tip of his tongue and any moment he might ask, "Is she really dead and gone or is this just some scam to get me out of the swamp and cleaned up?" With that skeptical glint in his eyes, he approached Grandmère Catherine's coffin slowly, hat in hand. About a foot or so away, he stopped and gazed down at her, waiting. When she didn't sit up and start screaming at him, he relaxed and turned back to me.

"How you doin', Ruby?" he asked.

"I'm all right, Grandpère," I said. My eyes were blood-shot but dry, for I had exhausted a reservoir of tears. He nodded and then he spun around and glared back at some of the women who were gazing at him with a veil of disgust visibly drawn over their faces.

"Well, what are you all lookin' at? Can't a man mourn his dead wife without you busybodies gaping at him and whispering behind his back? Go on with ya and give me some privacy," he cried.

Outraged and stunned, Grandmère Catherine's friends spun around and, with their heads bobbing, hurried out like a flock of frightened hens to gather on the galerie. Only Mrs. Thibodeau, Mrs. Livaudis, and Father Rush remained in the sitting room with Grandpère Jack and me.

"What happened to her?" Grandpère demanded, his green eyes still lit with fury.

"Her heart just gave out," Father Rush said, gazing warmly at Grandmère. He shook his head gently. "She spent all her energy on helping others, comforting and tending to the sick and the troubled. It finally took its toll on her, God bless her," he added.

"Well, I told her a hundred times if I told her once, to stop parading up and down the bayou to tend to everybody's needs but our own, but she wasn't one to listen. Stubborn to the day she died," Grandpère declared. "Just like most Cajun women," he added, staring at Mrs. Thibodeau and Mrs. Livaudis. They pulled back their shoulders and stiffened their necks like two peacocks.

"Oh, no," Father Rush said, smiling angelically, "you can't keep a soul as great as Mrs. Landry's soul from doing what she can to help the needy. Charity and compassion were her constant companions," he added.

Grandpère grunted. "Charity begins at home I told her, but she never listened to me. Well, I'm sorry she's gone. Don't know who's goin' to send fire and damnation my way. Don't know who's goin' to nag me and chastise me for doin' this or that," Grandpère declared, shaking his head.

"Oh, I expect someone will always be around to chastise you good, Jack Landry," Mrs. Thibodeau replied, nodding at him with her lips tightly pursed.

"Huh?" Grandpère stared at her a moment, but Mrs. Thibodeau had been around Grandmère Catherine too long not to have learned how to stare him down. He ran the back of his hand over his mouth and then shifted his eyes away and grunted again. "Yeah, I suppose," he said. The aromas from the kitchen caught his interest. "Well, I guess you ladies cooked up somethin', didn't you?" he asked.

"There's a spread in the kitchen, gumbo on the stove, and a pot of hot coffee brewing," Mrs. Livaudis said with visible reluctance.

"I'll get you something to eat, Grandpère," I said, rising. I had to do something, keep moving, keep busy.

"Why, thank you, Ruby. That's my only grandchild, you know," he told Father Rush. I snapped my head around sharply and glared at Grandpère. For a moment his eyes twinkled with that impish look and then he smiled and looked away, either not sensing or seeing what I knew or not caring about it. "She's all I got now," he continued. "Only family left. I got to look after her."

"And how do you expect to do that?" Mrs. Livaudis demanded. "You barely look after yourself, Jack Landry."

"I know what I do and I don't. A man can change, can't he? If something tragic like this occurs, a man can change. Can't he, Father? Ain't that so?"

"If it's truly in his heart to repent, anyone can," Father Rush replied, closing his eyes and pressing his hands together as if he were about to offer up a prayer to that effect.

"Hear that and that's a priest talking, not some gossip mouth," Grandpère said, nodding and poking the air between him and Mrs. Livaudis with his thick, long and dirty finger. "I got responsibilities now . . . a place to keep up, a granddaughter to see after, and I'm one to do what I say I'm goin' to do, when I say it."

"If you remember you've said it," Mrs. Thibodeau snapped. She was giving him no ground.

Grandpère smirked.

"Yeah, well, I'll remember. I'll remember," he repeated. He threw another look Grandmère Catherine's way, again as if he wanted to be sure she wasn't going to start screaming at him, and then he followed me out to the kitchen to get something to eat. He plopped his long, lanky body into a kitchen chair and dropped his hat on the floor. Then he looked around as I stirred up the gumbo and ladled a bowl for him.

"Ain't been in this house so long, it's like a strange place to me," he said. "And I built it myself!" I poured him a cup of coffee and then stepped back, folding my arms under my bosom and watching him go at the gumbo, shoving mouthful after mouthful in and swallowing with hardly a chew, the rice and roux running down his chin.

"When was the last time you ate something, Grandpère?" I asked. He paused for a moment and thought.

"I don't know . . . two days ago, I had some shrimp. Or was it some oysters?" He shrugged and continued to gulp his food. "But things are going to change for me now," he said, nodding between swallows. "I'm going to clean myself up, move back into my home, and have my granddaughter take care of me right and proper, and I'm going to do the same for her," he vowed.

"I can't believe Grandmère is actually dead and gone, Grandpère," I said, the tears choking my throat. He gulped some food and nodded.

"Me neither. I would have sworn on a stack of wild deuces that I'd go before she did. I thought that woman would outlive most of the world; she had that much grit in her. She was like some old tree root, just clinging to the things she believed in. I couldn't move her with a herd of elephants, not an inch off her ways."

"Nor could she move you, Grandpère," I quickly replied. He shrugged.

"Well, I'm just a stupid old Cajun trapper, too dumb to know right from wrong, yet I manage to survive. But I meant what I said out there, Ruby. I'm goin' to change somethin' awful and make things right for you. I swear it," he said, holding up his right palm, blotched with grime, the finger ends stained with tobacco. His deeply serious expression dissolved into a smile. "Could you give me another bowl of this. Ain't ate somethin' this good for ages. Beats the hell out of my swamp guk," he said, and chuckled to himself, a slight whistle coming through the gaps in his teeth as his shoulders shook.

I gave him some more and then I excused myself and went back to sit beside the coffin. I didn't like being away from Grandmère Catherine's side too long. Toward evening, some of Grandpère Jack's swamp cronies arrived supposedly to offer comfort and sympathy, but they were soon all going around behind the house to drink some whiskey and smoke their rolled, dark brown cigarettes.

Father Rush, Mrs. Thibodeau, and Mrs. Livaudis remained as long as they could and then promised to return early in the morning.

"You try to get yourself some rest, Ruby dear," Mrs. Thibodeau advised. "You're going to need your strength for the difficult days ahead."

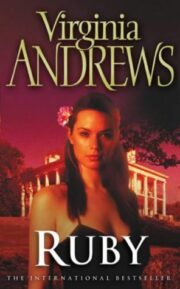

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.