Grandmère nodded.

"Yes, it's your face," she said, looking at the two, "but it's not you."

"Then who is it, Grandmère, and who is this man in the picture?"

She hesitated. I tried to wait patiently, but the butterflies in my stomach were flying around my heart, tickling it with their wings. I held my breath.

"I wasn't thinking when I sent you up to put the money in my chest," she began, "but maybe it was Providence's way of letting me know it's time."

"Time for what, Grandmère?"

"For you to know everything," she said, and sat back as if she had been struck, the now all too familiar exhaustion settling into her face again. "To know why I drove your Grandpère out and into the swamp to live like the animal he is." She closed her eyes and muttered under her breath, but my patience ran out.

"Who is the little girl if it's not me, Grandmère?" I demanded. Grandmère fixed her eyes on me, the crimson in her cheeks replaced by a paleness the color of oatmeal.

"It's your sister," she said.

"My sister!"

She nodded. She closed her eyes and kept them closed so long, I thought she wouldn't continue.

"And the man holding her hand . . ." she finally added. She didn't have to say it. The words were already settling in my mind. ". . . is your real father."

6

Room in My Heart

"If you knew who my father was all this time, Grandmère, why didn't you tell me? Where does he live? How did I get a sister? Why did it have to be kept such a secret, and why did this drive Grandpère into the swamp to live?" I fired my questions, one after the other, my voice impatient.

Grandmère Catherine closed her eyes. I knew it was her way to gather strength. It was as if she could reach into a second self and draw out the energy that made her the healer she was to the Cajun people in Terrebonne Parish.

My heart was thumping, a slow, heavy whacking in my chest that made me dizzy. The world around us seemed to grow very still. It was as if every owl, every insect, even the breeze was holding its breath in anticipation. After a moment Grandmère Catherine opened her dark eyes, eyes that were now shadowed and sad, and fixed them on me firmly as she shook her head ever so gently. I thought she released a soft moan before she began.

"I've dreaded this day for so long," Grandmère said, "dreaded it because once you've heard it all, you will know just how deeply into the depths of hell and damnation your Grandpère has gone. I've dreaded it because once you've heard it all you will know how much more tragic than you ever dreamed was your mother's short life, and I've dreaded it because once you've heard it all, you will know how much of your life, your family, your history, I have kept hidden from you.

"Please don't blame me for it, Ruby," she pleaded. "I have tried to be more than your Grandmère. I have tried to do what I thought was best for you.

"But at the same time," she continued, gazing down at her hands in her lap for a moment, "I must confess I have been somewhat selfish, too, for I wanted to keep you with me, wanted to keep something of my poor lost daughter beside me." She gazed up at me again. "If I have sinned, God forgive me, for my intentions were not evil and I did try to do the best I could for you, even though I admit, you would have had a much richer, much more comfortable life, if I had given you up the day you were born."

She sat back and sighed again as if a great weight had begun to be lifted from her shoulders and off her heart.

"Grandmère, no matter what you've done, no matter what you tell me, I will always love you just as I always have loved you," I assured her.

She smiled softly and then grew thoughtful and serious again.

"The truth is, Ruby, I couldn't have gone on; I would never have had the strength, even the spiritual strength I was born to have, if you hadn't been with me all these years. You have been my salvation and my hope, as you still are. However, now that I'm drawing closer and closer to the end of my days here, you must leave the bayou and go where you belong."

"Where do I belong, Grandmère?"

"In New Orleans."

"Because of my artwork?" I said, nodding in anticipation of her response. She had said it so many times before.

"Not only because of your talent," she replied, and then she sat forward and continued. "After Gabrielle had gotten herself into trouble with Paul Tate's father, she became a very withdrawn and solitary person. She didn't want to attend school anymore no matter how much I begged, so that except for the people who came around here, she saw no one. She became something of a wild thing, a true part of the bayou, a recluse who lived in nature and loved only natural things.

"And Nature accepted her with open arms. The beautiful birds she loved, loved her. I would look out and see how the marsh hawks watched over her, flew from tree to tree to follow her along the canals.

"She would always return with beautiful wild flowers in her hair when she went for a walk that lasted most of the afternoon. Gabrielle could spend hours sitting by the water, dazzled by its ebb and flow, hypnotized by the songs of the birds. I began to think the frogs that gathered around her actually spoke to her.

"Nothing harmed her. Even the alligators maintained a respectful distance, holding their eyes out of the water just enough to gaze at her as she walked along the shores of the marsh. It was as if the swamp and all the wildlife within it saw her as one of their own.

"She would take our pirogue and pole through those canals better than your Grandpère Jack. She certainly knew the water better, never getting hung up on anything. She went deep into the swamp, went to places rarely visited by human beings. If she had wanted to, she could have been a better swamp guide than your Grandpère," Grandmère added, nodding.

"As time went by, Gabrielle became even more beautiful. She seemed to draw on the natural beauty around her. Her face blossomed like a flower, her complexion was as soft as rose petals, her eyes were as bright as the noonday sunlight streaming through the goldenrod. She walked more softly than the marsh deer, who were never afraid to come right up to her. I saw her stroke their heads myself," Grandmère said, smiling warmly, deeply at her vivid memories, memories I longed to share.

"There was nothing sweeter to my ears than the sound of Gabrielle's laughter, no jewel more sparkling than the sparkle of her soft smile.

"When I was a little girl, much younger than you are now, my Grandmère told me stories about the so-called swamp fairies, nymphs that dwelled deep in the bayou and would show themselves only to the purest of heart. How I longed to catch sight of one. I never did, but I think I came the closest whenever I looked upon my own daughter, my own Gabrielle," she said and wiped a single fugitive tear from her cheek.

She took a deep breath, sat back, and continued.

"A little more than two years after Gabrielle's involvement with Mr. Tate, a very handsome, young Creole man came from New Orleans with his father to do some duck hunting in the swamp. In town they quickly learned about your Grandpère, who was, to give the devil his due," she muttered, "the best swamp guide in this bayou.

"This young man, Pierre Dumas, fell in love with your mother the moment he saw her emerge from the marsh with a baby rice bird on her shoulder. Her hair was long, midway down her back, and it had darkened to a rich, beautiful auburn color. She had my raven black eyes, Grandpère's dark complexion and teeth whiter than the keys of a brand-new accordion. Many a young man who had chanced by and had seen her had lost his heart quickly, but Gabrielle had become wary of men. Whenever one did stop to speak with her, she would simply toss a thin laugh his way and disappear so quickly he probably thought she really was a swamp ghost, one of my Grandmère's fairies," Grandmère Catherine said, smiling.

"But for some reason, she did not run from Pierre Dumas. Oh, he was tall and dashing in his elegant clothes, but later, she would tell me that she saw something gentle and loving in his face; she felt no threat. And I never saw a young man smitten as quickly as young Pierre Dumas was smitten. If he could have thrown off his rich clothes that very moment and gone into the swamp to live with Gabrielle then and there, he would have.

"But the truth was he was already married and had been for a little over two years. The Dumas family is one of the oldest and wealthiest families living in New Orleans," Grandmère said. "Those families guard their lineage very closely. Marriages are well thought out and arranged so as to keep up the social standing and protect their blue blood. Pierre's young wife also came from a well-respected, wealthy old Creole family.

"However, to the great chagrin of Pierre's father, Charles Dumas, Pierre's wife had been unable to get pregnant all this time. The prospect of no children was an unacceptable one to Pierre's father, and to Pierre as well. But they were good Catholics and divorce was not an alternative. Neither was adopting a child, for Charles Dumas wanted the Dumas blood to run through the veins of all of his grandchildren.

"Weekend after weekend, Pierre Dumas and his father, more often, just Pierre, would visit Houma and go duck hunting. Pierre began to spend more time with Gabrielle than he did with Grandpère Jack. Naturally, I was very worried. Even if Pierre wasn't already married, his father would not want him to bring back a wild Cajun girl with no rich lineage. I warned Gabrielle about him, but she simply looked at me and smiled as if I were trying to stop the wind.

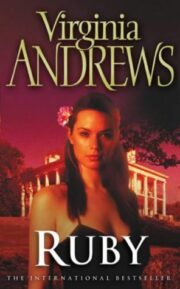

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.